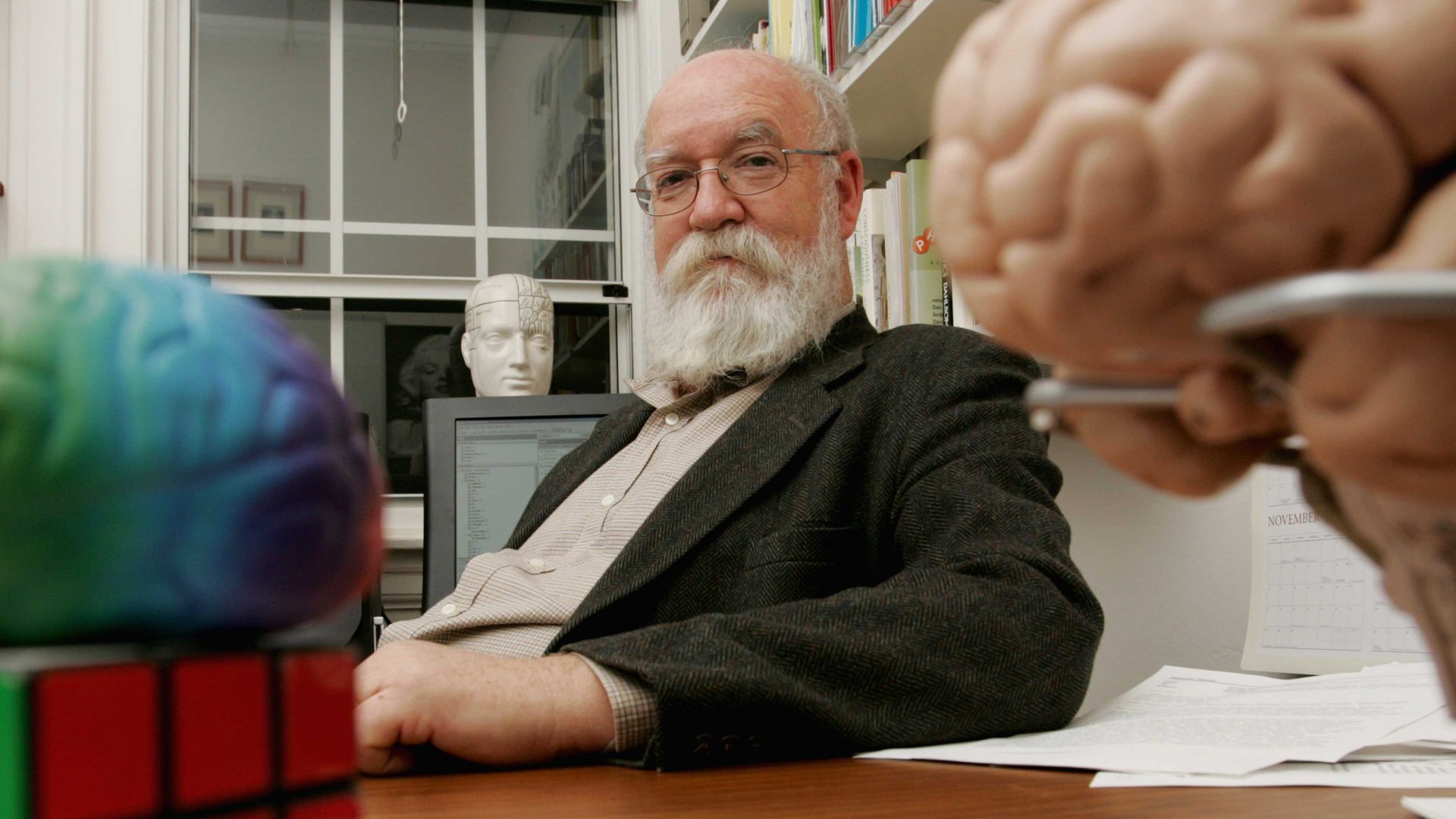

The American philosopher Daniel Dennett died last week on April 19, the same date that Charles Darwin died in 1882. This seemed appropriate.

Dennett, who, with his bushy white beard and substantial frame looked like a cross between Socrates and Father Christmas, thought Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection the best idea anyone had ever had. He thought it was even better than Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity, or Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

In his 1995 book Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, Dennett described the idea of evolution as a universal acid, something so corrosive that it could eat through anything, including key aspects of the existing worldview such as that the universe had been designed by God and that human beings occupied a special, exalted place and were radically different from animals.

David Hume, Dennett’s favourite philosopher, had come close to an evolutionary explanation of apparent design in the natural world in the 18th century in his brilliant Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, but it took Darwin’s genius to recognise a plausible mechanism for organisms’ gradual adaptation to environment.

The theory of evolution eliminated the need for a Designer with a capital D. It explained so much without the need for anything supernatural. Dennett hated supernatural explanations; he loved evolutionary explanations with equal zeal.

After Darwin there was no need for what he called “skyhooks”, deus ex machina explanations: instead, it was possible to begin to describe how complex thinking beings emerged from simpler ones, without any need to posit an intelligent designer.

Dennett was an atheist who, though not strident, didn’t shy from telling believers that their lives were based on an illusion. He was a key figure in the New Atheism, one of the so-called Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens.

In his 2006 book, Breaking the Spell, he explored the psychology of why so many people are drawn to supernatural explanations of our existence. When challenged, he admitted he couldn’t be absolutely certain that God didn’t exist, because you can’t conclusively prove a negative, but his conviction that God didn’t exist was at least as certain as any of his other strongly held beliefs.

Dennett will be remembered chiefly for his contributions to two areas. Above all, he was a philosopher of mind concerned to give a plausible explanation of how human consciousness evolved, how it is that as animals we are nevertheless able to reflect on our own existence and experience, how very simple matter that definitely doesn’t understand anything transforms itself into beings who can have experience.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who were happy to speculate about the mind from their armchairs, he travelled far and wide and learned from, and gained the respect of, many of the top evolutionary biologists, cognitive scientists and neuroscientists of his day.

He also took on one of the most intractable philosophical conundrums of all time: the paradox of free will. How is human free will, which we at least seem to have, compatible with the scientific assumption that if we knew enough about the complex web of causes that have produced each of us, all the genetic and environmental factors, it would be possible to know in advance which choices each of us would make next?

It looks as if there is no room at all for free will here, unless we posit some kind of ghostly mind stuff contravening the laws of physics causing our free actions. Against this, Dennett developed a compatibilist approach, that is, he did not see free will as inconsistent with scientific determinism. Instead, he argued that we have evolved with what he believed is the only type of free will worth wanting: the capacity to act without external coercive control and from decisions we have made.

Some philosophers saw that as a failed attempt to choose to have his cake and still be caused to eat it. When we act in this way we act freely, and that’s consistent with the deterministic account.

Although his ideas are not always easy to grasp, Dennett was a superb writer, witty, and always entertaining. But it’s not just through his writing that this important thinker will exert an influence long after his death.

He accepted numerous invitations to speak, and we are fortunate that as a result, though he hasn’t gone to heaven, he will have an afterlife through the many videos and podcasts that outlive him.