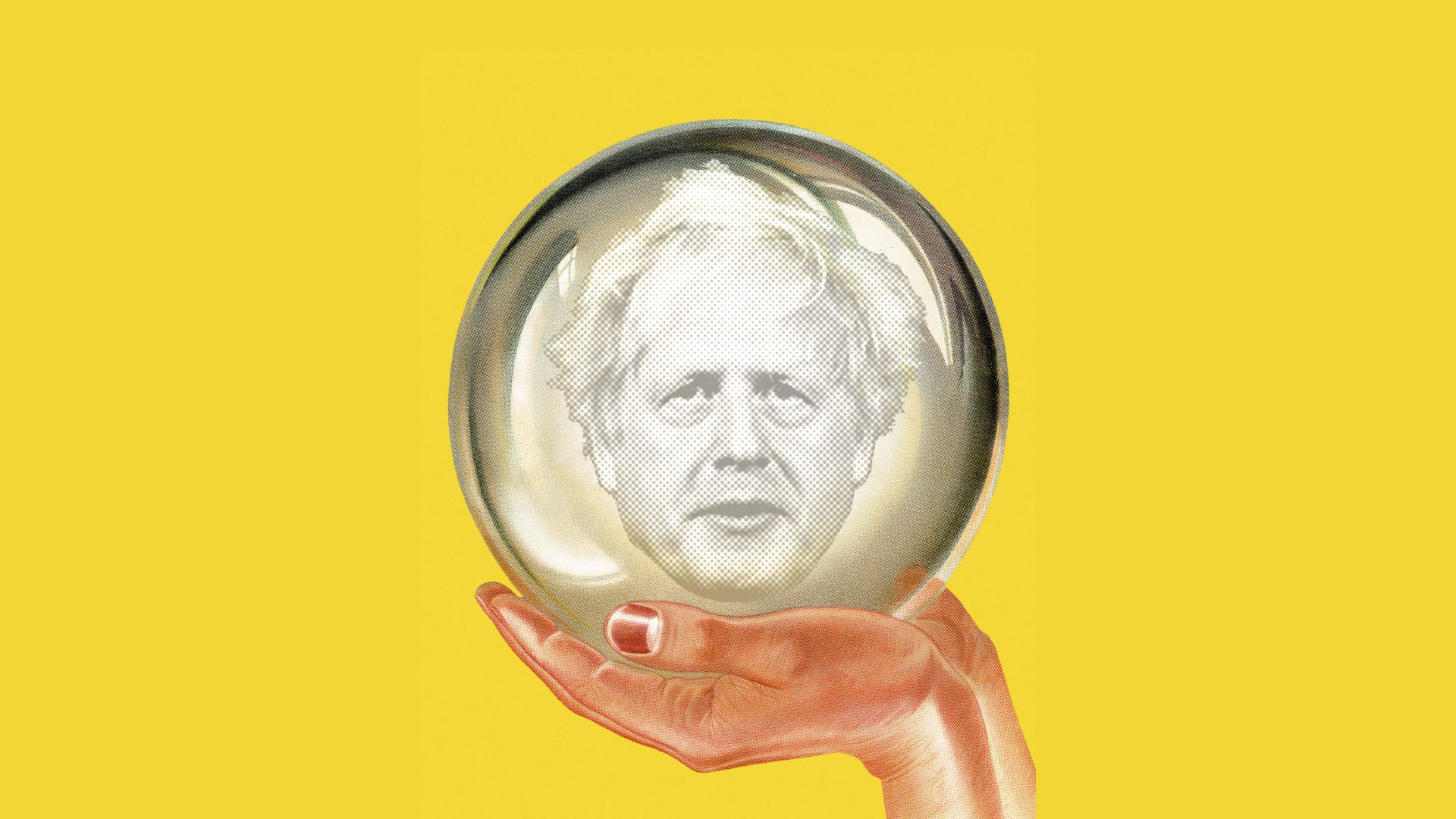

The remarkable Professor Jon Tonge, the so-called “Mystic Meg of political forecasting”, predicted the outcome of the recent no-confidence vote within one vote. It would be nice if we had a reliable seer like him who could give us a specific date by which Boris Johnson would be gone from No 10. But we don’t.

Why not? Many commentators feel Johnson’s demise is inevitable, and that it will be his party that axes him. But when exactly? Is it just wishful thinking to believe that he won’t serve a second term as prime minister? All attempts at an answer to these questions are highly speculative. Why can’t we work these things out with precision?

Some pundits are using the past as a guide. Johnson had a lower percentage of party support (59%) than Theresa May did (63%) in a similar vote in 2018. She resigned six months later. So, he’ll be gone within six months too, right? Perhaps. But some predictions are much easier to get right than others. Working out the likely voting pattern of a few hundred MPs, many of whom had already declared their intentions, is very different from giving a long-term weather forecast. Predicting Boris Johnson’s future in politics is a bit like trying to predict the weather next year. Chaos theory can help us understand this.

The mathematician Marcus du Sautoy has a nice way of demonstrating chaos theory. He whips out a pendulum made of two bits of wood hinged in the middle. When he releases the pendulum, it swings in a variety of ways, sometimes looping over itself, sometimes not, the momentum increasing and decreasing. It looks a little mad, and sometimes people watching him doing this demonstration laugh, perhaps because of the unpredictability of what it will do next. It seems to suddenly lurch and then swing the other way. He then swings the pendulum again, trying as hard as possible to start from precisely the same place as with the previous swing. This time it moves in a different, equally bizarre fashion, following a similar but different trajectory as it twists and whirls until finally coming to rest.

The point of all this is to demonstrate something that is not obvious. With certain systems, even some that appear very simple, a tiny difference in the starting point (or some incidental intervention once the process has started), can lead to a radically different outcome. They’re extremely sensitive to initial conditions. So small inaccuracies about what’s going on can have a huge impact on expectations.

This makes prediction of what will happen in these kinds of systems incredibly difficult, if not impossible. Even something so apparently straightforward as a hinged pendulum would bamboozle physicists attempting to map its likely course. A fraction out, and the pattern will be almost completely different from the prediction. This is surprising because intuitively you’d think that a small difference shouldn’t affect the result so much. If you start the pendulum from almost exactly the same place its path should be more or less the same. But it isn’t.

Henri Poincaré noticed how difficult long-term weather forecasting was and began to explore what was going on. Edward Lorenz went on to develop chaos theory and coined the term “the Butterfly Effect” to emphasise how a seemingly minor event could result in a major difference in outcome: he speculated that a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil might affect how a tornado develops in Texas. Lorenz captured this in his description of chaos as “‘when the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future.”

Not every sort of system is so sensitive to minor changes in starting conditions like this. Some are highly predictable. I have, for example, quite a lot of latitude about which bit of my keyboard key I tap with my finger, to produce the same outcome – the same letter appearing on my screen. Some aspects of politics may be a bit like this, too. But most aren’t.

Sadly, there aren’t so many butterflies flapping their wings in the UK this summer, but I’m holding out hope that the spontaneous booing from the crowd as the Johnsons arrived at St Paul’s for the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee thanksgiving service could be the minor event that triggers the beginning of the end for the prime minister.

Either that or a red admiral butterfly like the one I saw in central London yesterday, opening and closing its wings in the summer sun.