Philosophers can be quirky. Take Ludwig Wittgenstein. His rooms in Cambridge were bare except for two deck chairs, a camp bed, and sets of identical clothes in a wardrobe. When asked what he wanted to eat, he said he didn’t care just so long as it was the same thing every day. He refused to lunch at high table in Trinity College, not wanting to set himself literally above other people. But then he had a special table made at the same height as that of the students so he could sit alone.

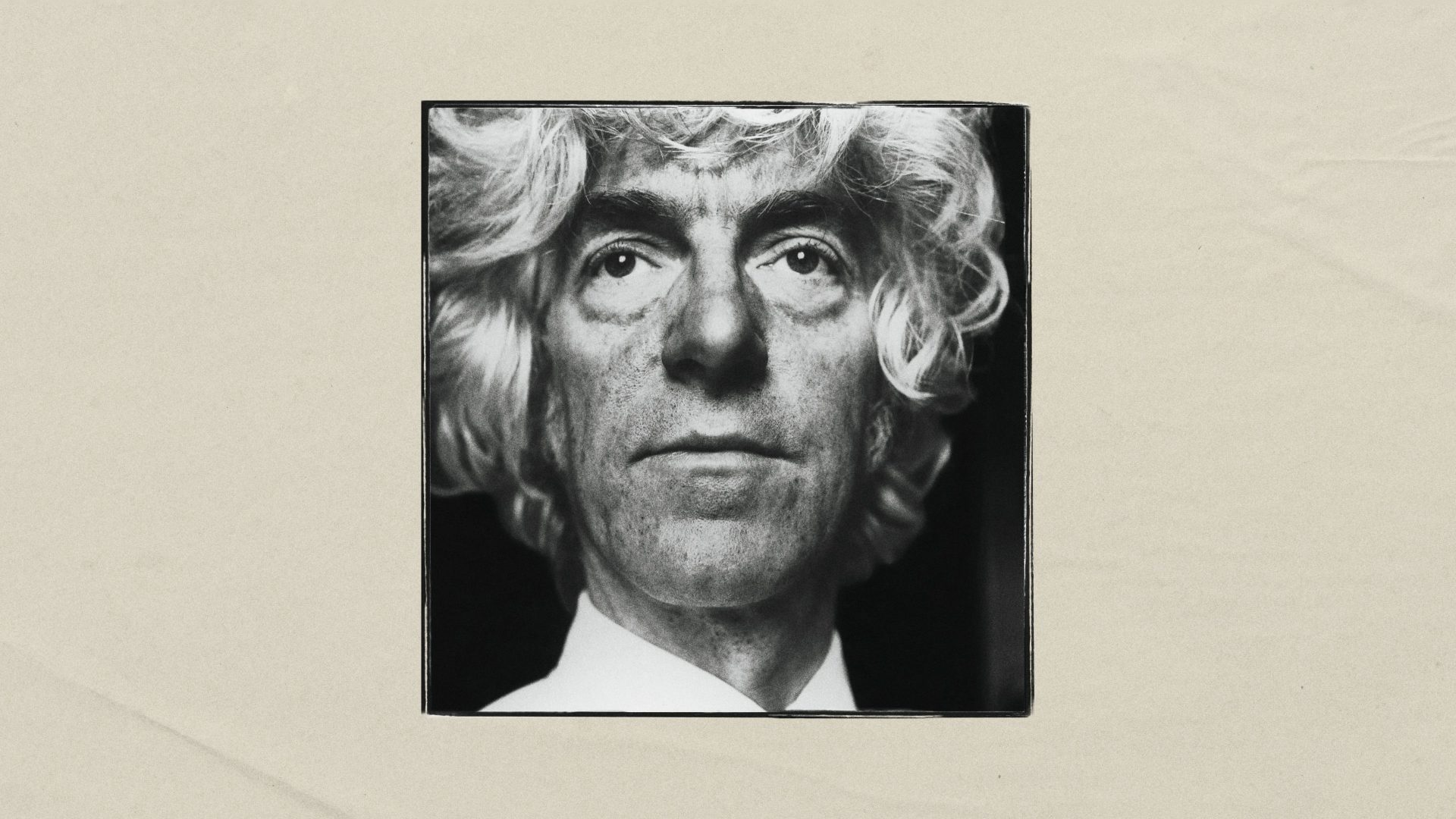

The far less famous Oxford philosopher Derek Parfit, who died at the beginning of 2017, was even quirkier than Wittgenstein as readers of David Edmonds’ very readable biography published by Princeton University Press last week will appreciate.

By always wearing grey trousers, a white shirt, and a red tie, he avoided wasting time thinking about what to wear. He cleaned his teeth obsessively for over an hour a day, reading all the time.

Wittgenstein was at various periods in his life completely immersed in his work, so much so that when he was living in an isolated cabin north of Bergen and anyone spoke to him, he told them to go away. When a local greeted him cheerily, he allegedly shouted that it would take him two weeks to get back to the point in his thought he’d achieved before the interruption. Parfit had that same intensity but was far more polite in his interactions.

In later life, Parfit worked with a passionate intensity too. Afraid of wasting a minute, he carried on reading while making the instant coffee that fuelled him, using hot water direct from the tap.

I checked this story with his widow Janet Radcliffe Richards because it sounded like a parody: she confirmed its truth, adding that sometimes he wouldn’t even wait for the water to get warm.

His only exercise was on an indoor bike wearing just underpants – or sometimes not even those – reading all the time. The bike was in front of a window overlooking the street. Wherever he was, Oxford, New York, even on holiday in Venice, he spent almost every waking hour inside hunched over a book or his laptop.

Wittgenstein barely published anything, and his writing was elegant and spare. One reading of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is that what matters most in life is beyond meaningful expression. That’s the force of the line “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”.

In contrast, Parfit’s later years were devoted to pinning down what matters, and spelling this out in his sprawling three-volume book On What Matters – probably the longest and densest work of philosophy published this century. Parfit’s parents were missionaries, and as Edmonds points out, he displayed a missionary zeal in his attempt to demonstrate conclusively that morality isn’t subjective.

If he managed this (which seems unlikely) few readers will have the stamina to work through every page of this magnum opus to find out how he got there.

On What Matters was originally to be called Climbing the Mountain. I confess to not even having got beyond its foothills. Life is short. I suspect his earlier and more accessible work on personal identity and morality will have a greater impact.

Parfit used a range of thought experiments, some inspired by the teletransporter in Star Trek, to overturn conventional views about what makes each of us the same person over time. What would we say if our bodies were de-materialised and then re-materialised in another place from other components? Would the person “teletransported” to another place be the same person?

One of his main conclusions was that the metaphysical question of whether we continue to exist or not as the same person in these “Beam me up, Scotty!” examples or indeed in the real future, isn’t what really matters. What matters is our psychological continuity, and that can come in degrees.

The upshot is that, according to Parfit, if we see clearly what we are, we can become less attached to our own future selves than is customary. We can come to recognise that our future selves are more like other people than we usually think of them, a view that has much in common with the Buddhist doctrine of no-self.

In an appendix to his first book Reasons and Persons, Parfit even cited words attributed to the Buddha to the same effect: “There exists no Individual, it is only a conventional name given to a set of elements”.