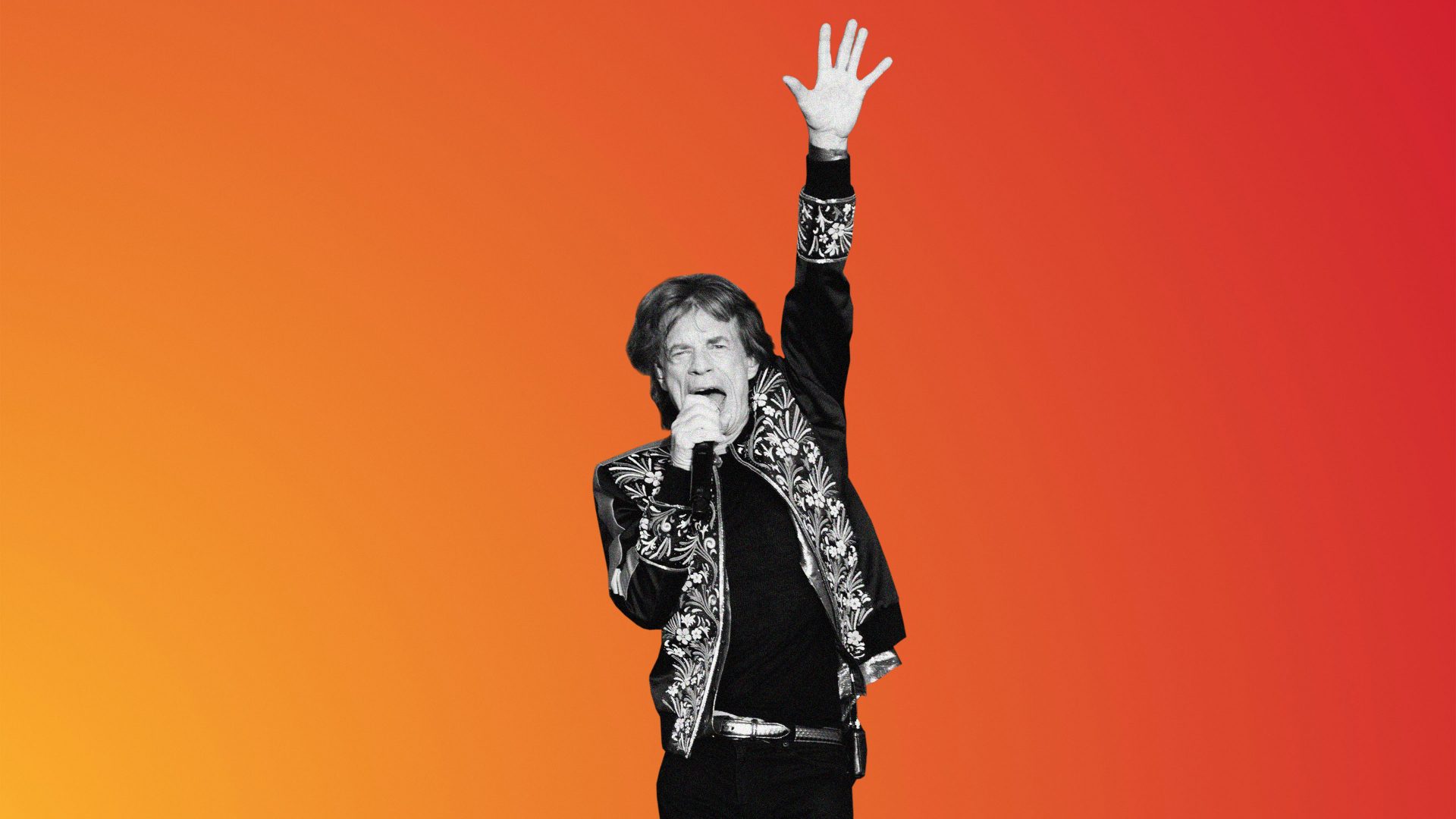

In the last few weeks, Paul McCartney (80) became the oldest solo artist to headline Glastonbury, and Diana Ross appeared on the same stage at 78. Then Mick Jagger (also 78) sang and strutted in Hyde Park. None seem their age. McCartney looks so young that there’s even a conspiracy theory that he’s been replaced by a lookalike.

Ageing is, of course, a biological phenomenon, but it’s also a social phenomenon. One of the few philosophers to write in any depth about the topic, Simone de Beauvoir, had a lot to say about both aspects, much of it insightful if pessimistic. In her 600-page book Old Age she tells it straight:

“It is an empiric and universal truth that after a certain number of years the human organism undergoes a decline. The process is inescapable.”

This is a given of the human condition for anyone who lives beyond middle age. You can fight it, but you won’t win. Young people often stigmatise old people, particularly those who show visible signs of ageing. For most, it doesn’t work out as well as it has done for McCartney, Ross and Jagger.

De Beauvoir admits to being scared about ageing. It brings a reduction in physical capabilities, a loss of some mental faculties, and an alteration in our attitude to the world.

Even McCartney, Ross and Jagger have slowed down. They don’t sound or move quite like they used to. They’re discussed differently, too. Today’s commentators make a point of mentioning their age rather than just their music. I did it at the start of this column.

De Beauvoir noted how children and old people both get described as extraordinary for their age. Her explanation, given through the eyes of an ageist, was that “the extraordinariness lies in their behaving like human beings when they are either not yet or no longer men.”

Skye Cleary, in her book How to Be You: Simone de Beauvoir and the Art of Authentic Living, writes: “A common cliche is that you are only as old as you feel, but that is oversimplifying. Other people also define us.”

Exactly. It isn’t just a matter of how you feel. Diana Ross says she feels 48. But that doesn’t magically take 30 years off her real age. We are social beings. It’s common for older people to be marginalised, ignored, excluded, or neglected. McCartney, Ross and Jagger are exceptions that prove the rule here, but some of that has to do with the profit that can be made from their continuing to perform. De Beauvoir wrote that in the eyes of society a very old person is generally “a corpse under suspended sentence”.

This might seem unduly pessimistic. Perhaps it is, especially in relation to those in a position of privilege and wealth. Some of the most powerful people in the world are old white men – Joe Biden (79) for example. And many people find new interests and achieve their dreams only after retirement.

However, as de Beauvoir noted, as we age, we lose people and what we have experienced with them, too. The Rolling Stones began their Hyde Park concert with a video of their former drummer, Charlie Watts, who died last year. McCartney mentioned George Harrison and John Lennon. So many shared memories have been buried with them.

The older any of us get, the more friends, colleagues, former lovers, and relatives die.

De Beauvoir wrote about how parts of her past were lost with the death of friends: her arguments with Albert Camus, her long discussions in his studio with the sculptor Alberto Giacometti. She described what was left as a “frigid imitation” of their times together.

Younger people experience this too, of course, when people dear to them die; but for the very old, the deaths of so many of their contemporaries becomes a feature of life, people with whom they may have spent decades.

This is just a glimpse, but for de Beauvoir ageing was all about decline, the weight of our past, and social prejudices, with younger people pretending that they won’t themselves end up old, a kind of self-deception motivated by fear of what the future holds for them.

Although she recognised that some cultures venerate the old, most don’t. The only hope de Beauvoir saw for the old was in their continuing involvement with the world: devotion to other people, groups or causes. Love, indignation and compassion can keep us from living a parody of our former lives. There might even be time to sing a new song or two.