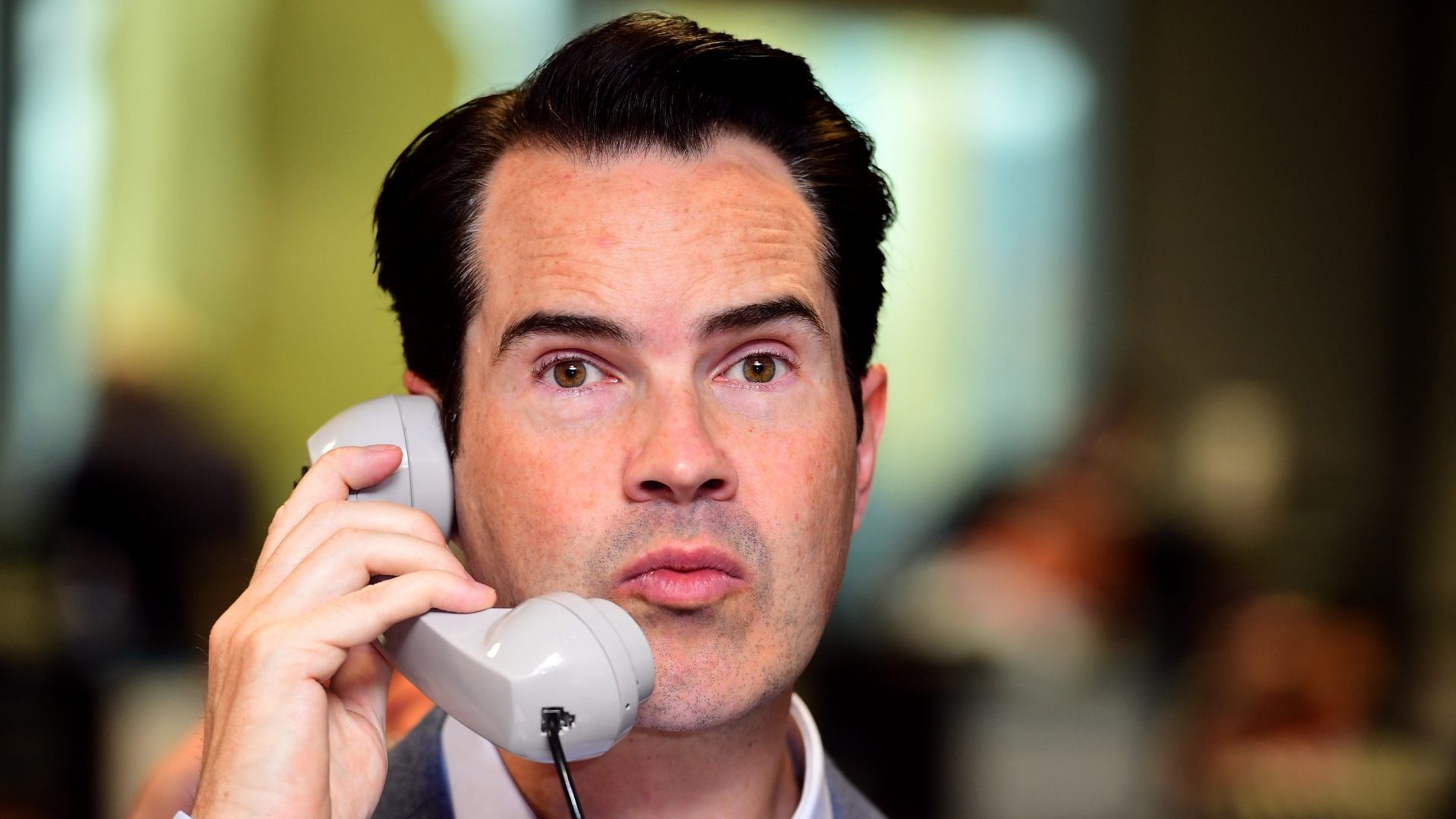

Jimmy Carr is in trouble for a joke about the Holocaust. In his Netflix show, His Dark Material, after mentioning that we all know about the deaths of six million Jews, he says: “But they never mention the thousands of Gypsies that were killed by the Nazis”, then adds in a deadpan voice that people are unwilling to talk about the positives.

The point of the show is to push comedy to its limits. But this was more than bad taste. Many people took it as straightforward racism.

It’s genuinely shocking to hear someone make a joke about the murder of many thousands of people, vilifying a much-persecuted group in the process. Setting aside the question of whether Carr broke the law – because some read his joke as an incitement to racial hatred, and we have laws against that – what light can philosophy shed on this?

In his book On Liberty, first published in 1859, John Stuart Mill argued for extensive freedom of expression. Without free speech, falsehoods can’t easily be challenged. Censors are fallible and may end up censoring valuable ideas, or ideas that, though false, could stimulate others to think more clearly.

Mill believed that without a collision of different sorts of thoughts, a marketplace of ideas, we risk becoming intellectually complacent, holding our beliefs as dead dogma. Far better to have a wide range of ideas in circulation, including ideas that some find extremely distasteful.

For Mill, the limit of free expression in a civilised society is the point where it becomes incitement to violence. This is context-dependent: the same words spoken to an angry mob have very different force when written in a newspaper editorial, so it is not always easy to draw a line.

Speech that is merely offensive should be tolerated: criticised perhaps, but not censored. The state should intervene to prevent incitement to violence.

For those who follow Mill, the key question is, does Carr’s joke incite violence? Certainly, he didn’t urge violence against Gypsies, and I’m sure he wouldn’t advocate it.

But the predictable consequences of targeting a group like this could be that those who are more prone to resort to violence are triggered by it. Yet unravelling cause and effect in particular cases is notoriously difficult, and so perhaps we can give him the benefit of the doubt and categorise this as extremely offensive, but not a direct incitement.

There’s a tradition in philosophy of setting out the best possible version of an opponent’s argument, using what is sometimes called The Principle of Charity. This is usually a prelude to demolishing it.

The idea is to criticise the strongest version of an argument or position, and so avoid the accusation that you have knocked a Strawman, a caricature of a position.

What happens if we apply this principle here? What is the best defence that could be made for Carr’s apparently indefensible joke?

The answer, I think, is that it needs to be taken in context. That’s where meaning is generated, not simply in the literal definitions of words.

The context here is a show about pushing the limits of comedy and making jokes about things you’re not supposed to joke about, including rape.

It might look as if Carr is just telling a very nasty joke, the kind of thing that racist comedians did in the 1970s. But in this context, perhaps, just perhaps, it is different.

This could be a joke heavy with irony, an irony signalled by the delivery, the aim of the show, and his quip that it is “a career-ender”. On this reading, Carr meant to tell an unacceptable joke but within quotation marks.

This was a mention rather than a use, as philosophers of language would put it. By this time in the show he has his audience on his side, and people start to laugh because of the set-up and punchline format and his timing. That throws them into the awkward position of seeming to condone racism because they have found his ironic quotation of a racist joke funny. They squirm when they realise this. Taken this way, Carr is teasing the audience, holding a mirror up to their own racism.

This could be what he was attempting. But even if we are charitable and take that as his aim, intentions aren’t everything. Delivering casually racist jokes, even in an ironic register, can normalise contempt and hatred for a minority group. It’s right to feel uncomfortable about this.