While Priti Patel has been busy looking for ways to send migrants to Rwanda, there has been a flow of traffic in the other direction – from Africa to Europe. The swallows have arrived. So it’s definitely summer.

Walking by the Thames near Iffley, I’ve been watching them skimming the river at great speed, hunting for insects, their neat bodies and distinctive forked tails glimpsed as they twist and manoeuvre with a flick of their wings. Then they vanish for a few seconds before reappearing and swooping low over the riverbank. They nest every year under a graffiti-covered bridge over which traffic rumbles on the bypass throughout the day and night.

The philosopher Aristotle, who was also a brilliant zoologist, was fascinated by these remarkable birds. He wrote of their ingenuity in building mud nests, and their diligence in making sure each of their nestlings was properly fed and trained to defecate outside the nest. But his most famous swallow reference is in Book One of his Nicomachean Ethics where he declared: “One swallow doesn’t make a summer.”

This was in the context of a discussion of what makes a successful life for a human being. He believed that what we seek is “eudaimonia”. This word is sometimes translated as “happiness” and at other times as “flourishing”, though neither quite nails it. Eudaimonia is sought for its own sake but is different from pleasure.

Unlike Jeremy Bentham and the utilitarians, Aristotle didn’t advocate maximising blissful mental states. It’s not all about frissons and highs, though he wasn’t against them. He was scathing, though, about those who spend their lives simply pursuing their own pleasure. He didn’t equate success in life with material goods, or with public recognition, either.

Eudaimonia is something which a human life can objectively have if lived well. That happens when people live virtuously. A virtue is a pattern of behaviour, feeling and thought that lies between two extremes. Bravery, for instance, is between cowardice and foolhardiness. Virtues are dispositions to act in certain ways because we feel that this is right, and because we have good reasons to back us up.

Swallows can make nests, and care for their young, but can’t reflect on these activities. We, however, can reflect on what we do and ought to do. Acting from a combination of reason and appropriate feeling is how human beings flourish. We need to have a certain amount of luck too, not just in our education in the broadest sense, but also in our material and physical wellbeing. If you lack resources to live at a basic level it is, Aristotle recognised, almost impossible to live a good life.

Flourishing in this way isn’t just about how we feel. We can be misled. Whether we are truly eudaimon is a question of whether we are acting virtuously, not of whether we tell ourselves that we are.

Nor is it sufficient to do one or two good things in life. That comment about a single swallow not making a summer points to that. We should judge people over a far longer period of time.

For Aristotle, living well was ultimately about achieving our individual potential over a whole lifespan. This involves setting clear goals for ourselves, reflecting on these and how they interlock with the interests of other people, making the best that we can from the cards we’ve been dealt.

Such a life won’t be one of retreat to solitude and avoidance of the world. We need to engage with other people – friends, family, strangers.

Each of us is capable of a different level of virtue, and we should acknowledge that there is no definitive set of rules to follow. This is not a one-size-fits-all approach. We have to adapt to circumstances.

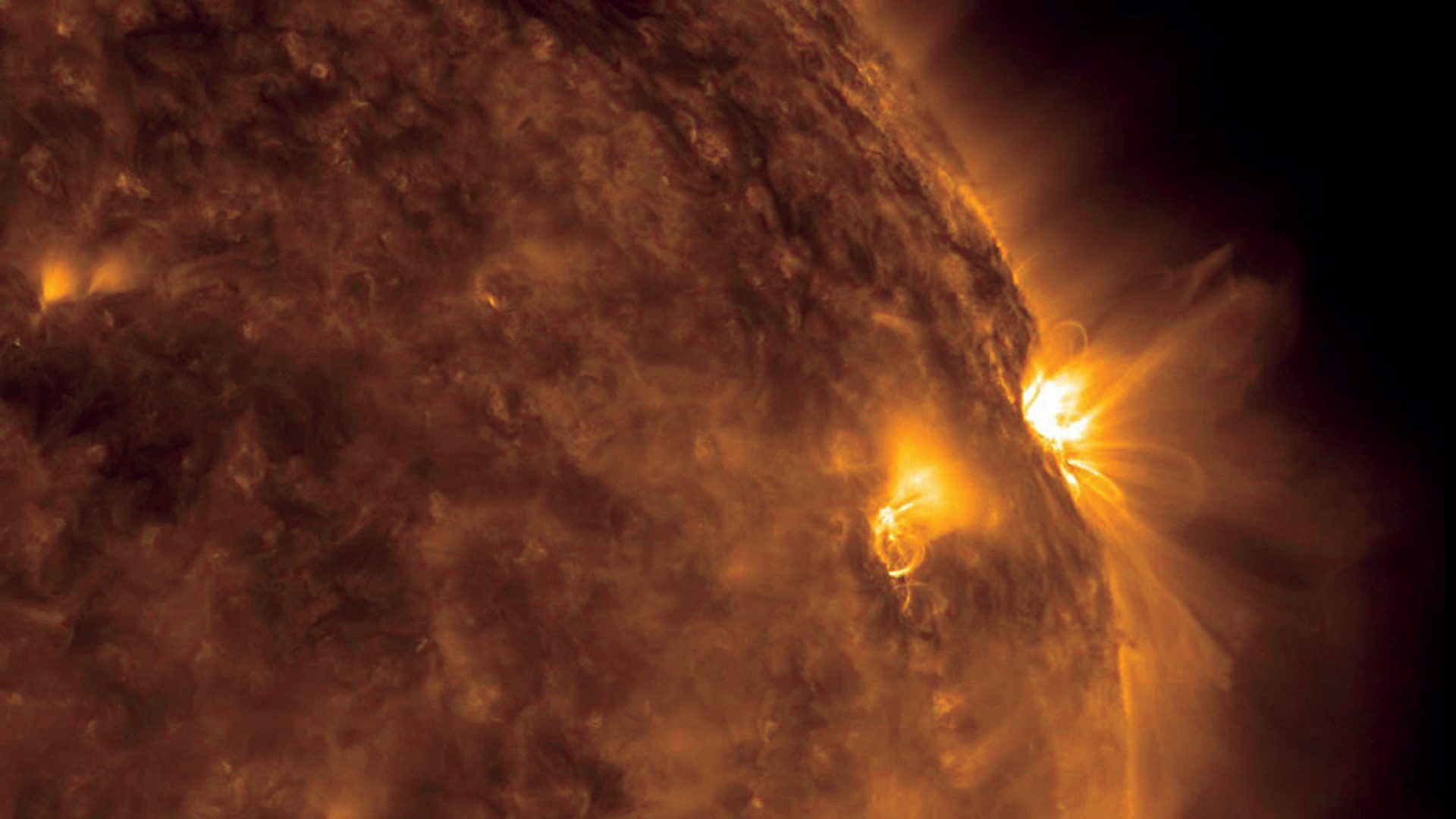

There are fewer swallows than there were last year. This is probably because of unsettled weather caused by global warming. And global warming ultimately stems from the unvirtuous behaviour of individuals, companies, and nations. These birds fly over 6,000 miles to get to Europe and there is so much that can go wrong on that arduous journey.

We’re told, in a strange mixed metaphor, that swallows are the canaries in the coalmine of climate catastrophe. When these beautiful birds fail to arrive, we’ll know things have gone seriously wrong. Perhaps we’re already there.

Diminishing numbers could be an early sign. I hope not. There might still be time to act virtuously and avert the disaster that a summer without swallows would presage.