By the time Gary Hollingworth got home on June 18, 1984, he was shattered.

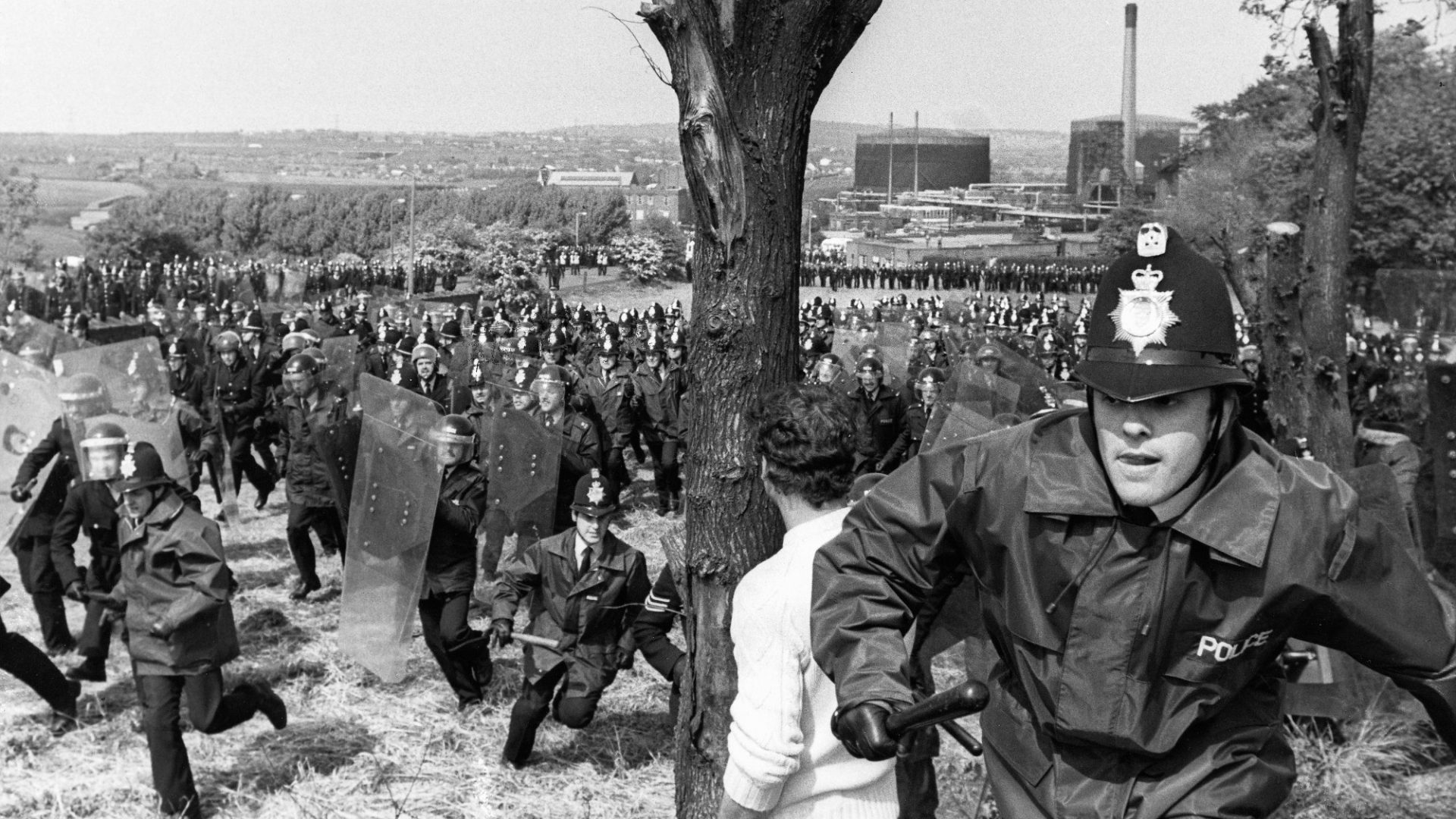

A 28-year-old miner at Grimethorpe Colliery in South Yorkshire, Gary had spent most of the day at the mass picket at Orgreave coking works, 12 miles south. He had been charged by mounted police, chased by snatch squads with shields and truncheons, and his friend Brian had three ribs broken after being dragged behind police lines and beaten. And yet in truth it hadn’t seemed so different to some of the other picket lines he’d been on. The real shock, he remembers years later, came from what he saw on the BBC 9 o’clock news.

The cavalry charges at Orgreave, as has since been confirmed, were unprovoked. Only afterwards did pickets throw stones, at least partly in self-defence. The BBC News footage reversed this order, implying that the pickets had attacked the police. Interviews with senior police officers and Margaret Thatcher herself restated this version of events.

Watching the report gave Gary a shaky, unreal feeling, akin to panic. The battle had been much bigger and more violent than he had realised. But what stupefied him was the account given by the BBC, the police and the prime minister.

“We were just from these little villages,” he says, looking back. “We believed things like the BBC, and what we’d call ‘posh’ papers. But you wondered how could they all be saying the same thing, when you knew it was wrong? And then it kept happening all through the strike. I think people never looked at the media or politics the same after that.”

Gary is my cousin, and we grew up in the Dearne Valley in South Yorkshire. Thirty-two years after the battle of Orgreave, as the EU referendum campaign sparked debates about voters in areas blighted by industrial decline – as the Dearne by then was – I thought about his response to that infamous footage reversal.

At the time, it was not unusual to hear people in the area claiming that the EU had forced the closure of pits after the strike – a baseless conspiracy theory that still lingers. Quora, the online Q&A site, still has a thriving debate in response to the question: “Is there any truth in the rumour that Margaret Thatcher was ordered to close the mines by the EU as a step towards globalisation?”

Ideas like this would be part of the reason for the high Leave vote in post-industrial regions, particularly former coalfield areas. It would be suggested later that this was down to feelings of anger or marginalisation arising from economic problems in those areas.

It would be hard to ignore the anger and the economics, but the willingness of people to regard the EU as malevolent was too easily put down to stupidity. In former mining areas at least, it was more complicated than that, because the roots of that credulity run deep and dark as a pit shaft, right back to the beginnings of the post-truth era in 1984.

Miners were the first of the organised working class to take part in parliamentary politics, with two colliers elected in 1874 as joint trade union-Liberal Party candidates, and since then there had always been high levels of political engagement and class consciousness in mining areas. Children were taught that animosity between miners and the ruling class was a sort of natural order; Gary and I learned it from our grandma’s stories about Churchill and Lady Astor and the 1926 strike.

Even among the less politically minded there prevailed a passive cynicism towards politicians famously described by Richard Hoggart in The Uses of Literacy. It was a kind of consensus hostility, an intense dislike held in equilibrium.

But there was not a widespread belief in active plotting or malevolent lying, or a sense of being involved in a zero-sum political game. Very few people in those communities would have thought they could ever be important enough – hence perhaps the irony that the miners initially underestimated Thatcher’s determination to win, while she paid them the backhanded compliment of not underestimating theirs.

The covert and centrally planned nature of the government’s attack revealed itself gradually, at first in small details and hearsay in the pit towns and villages. Familiar local bobbies on picket lines were replaced by urban forces from distant places like the West Midlands or London. They wore no identifying numbers on the epaulettes. The back doors of lorry trailers at one protest swung open to reveal men with radios, screens and charts. Men started appearing on picket lines that nobody recognised. The cars of known pickets were vandalised. There were rumours of soldiers deployed in police uniform.

By the summer those rumours would swell to include stories about a businessman touring the coalfields of Nottinghamshire in a chauffeur-driven Mercedes recruiting men for an anti-strike movement, and using former SAS men as bodyguards. This would turn out to be David Hart, the notorious adviser to National Coal Board chairman Ian MacGregor.

Some people also began to raise questions about the reporting of the strike – this was not helped, it has to be said, by the NUM leadership and pickets themselves, whose hostility towards unknown journalists sent them scuttling off to “safety” behind police lines.

Then came Orgreave, followed by a trial that revealed that the police were using tactics based on methods developed in Northern Ireland. Through autumn 1984 the violence on picket lines intensified, Hart cultivated the anti-strike group, Tim Bell of Saatchi & Saatchi advised on presentation, the Labour leadership prevaricated, and there were huge police operations to transport non-striking miners to the pits.

Geoff, a friend from Wakefield who returned to work at Christmas, told me: “That first morning was the most frightening thing I’d ever seen. It was all secret, but you were told you had to be at Woolley Edge [a service station on the M1] at 6am. There were floodlights, barriers across all the roads, more police than you can imagine. That’s when I realised what the government was doing. That’s when I knew every rumour was true.”

In mining communities, the combined experience during 1984 of the policing, the inaccurate reporting and government propaganda shattered trust not only in the Conservative government, but in institutions themselves. The basic good faith underlying Britain’s post-1945 consensus had gone, along with the idea that at some fundamental level you could trust the state. After the strike ended in March 1985 it made more sense to believe in the state as a matrix of conspiracies. Little that came afterwards changed that.

There were admissions of guilt, including from the BBC and South Yorkshire police, over Orgreave, but by the time they came, the Coal Board was already closing the pits. The closures themselves were so badly planned that it looked like more vindictiveness.

Shutting down a pit in a town where it is the main source of employment did not necessarily have to blight that community with unemployment, poverty and crime, so long as there were nearby pits. But the pits were closed in geographical clusters, and in some cases people interpreted this as punishment for militancy. Investment under New Labour didn’t save them, and the effects are still felt in places like the Dearne today.

For many people there, the argument made in 2016 that the EU had made them better off felt not only unconvincing, but also like part of the Thatcherite argument that closing uneconomic pits was good for prosperity. True, 40 years might be a long time to hold a grudge, but these communities, or at least the older members of them, retain a strong sense of history. In 1972, when the miners won a famous strike that set the tone for labour relations in the 1970s, it was commonly seen as revenge for the defeat of the 1926 General Strike.

This explains why the residents of ex-mining communities were so receptive to Leave’s depiction of the EU as a distant, malevolent force, and why Cummings didn’t need to prove anything he said. It was that great populist debating trick: of course the publicly available information contradicted them! You don’t think something like the EU was going to let the truth get out there, did you?

There was another factor in play during the Brexit campaign: immigration. The frequent claim that freedom of movement led to lower wages for British workers has, if we can be honest about it, some truth to it in these kinds of areas. The bulk of new jobs in ex-mining districts have been low-skilled, or unskilled, and in 2017, a 10 percentage point rise in the proportion of immigrants was shown to be associated with a 2.6% reduction in pay.

Pay is easy to measure, conditions less so, and in my experience most of the complaints made against immigrant workers were not about pay, and less about immigrants themselves. The problem was their use as bargaining chips by unscrupulous managers. “If you don’t fucking like it, I’ve a queue of Kosovans who’ll do it for half of what you want,” an uncle, formerly in charge of a colliery lamp room, was told by a manager at a car factory. He had been protesting with other employees – most of them former NUM members, among whom the old solidarity remains – about overtime conditions.

I have heard much the same from warehouse workers in other former coalfields; some blamed the immigrants themselves, others blamed the managers, but most saw leaving the EU as a way of weakening the managers’ power.

There is another dimension to this, to do with skills. By the 1980s, any coal mine required hundreds of highly skilled, highly trained operatives and engineers, and an entire workforce with strong communication and teamwork skills. But when pits closed, the agencies put in place to find employment and training focused – exclusively in some cases – on low-skilled and unskilled work.

In Up Sticks and a Job For Life, an oral history of the Selby Coalfield, people recall employment advisers being invited to go underground to better understand what people did – and every one refusing the offer.

So it was that when Gary, a trained ventilation engineer, finally gave up in the early 1990s, he asked if the agency assigned to his area could help him fulfil a lifelong ambition and train to become a teacher. No, they said. All we have are building jobs. Gary eventually became a senior social worker. Geoff is a dental nurse. Communication and teamwork. How many other abilities were ignored? How many more transferable skills went unrecognised and unused?

Forty years ago, our pit villages and towns were subjected to a blitz of disinformation and misrepresentation that made people believe institutions couldn’t tell the truth. That, together with the suffering that was inflicted, made them cynical, and vulnerable to people who told persuasive stories that validated their cynicism.

What might have been different had some empathy and imagination been applied during and after the strike? And how might the last 10 years have turned out if the government back then had had ambition for what our old industrial communities might have become, instead of retribution for what they had been?

An Uncivil War, a new oral history of the Battle of Orgreave, is available for £20 from the New European shop.