Lately, there’s been a nostalgic buzz among Germans surrounding Maggie Thatcher, die Eiserne Lady, despite her less-than-favourable opinion of us, because she’s mostly associated here with crushing union strikes.

Many German commuters and travellers would wholeheartedly agree with her about “the enemy within”, thinking of one individual in particular. But before we delve into that, let’s put things into perspective.

Reuters recently dubbed our series of strikes as the “winter of discontent”, but even the past three months pale in comparison to the UK original in the late 1970s. Moreover, German nature and language don’t really align with “discontent” – we’re downright furious about the plethora of strikes affecting trains, the underground, buses, airport security, ground crews and pilots. It feels like France. But it isn’t.

Between 2020 and 2022, Germany saw an average of 17.8 working days lost per 1,000 employees due to strikes, a far cry from 37.3 in Spain, 79.1 in France and 88.9 in the UK. Under our system, only trade unions are permitted to organise industrial action, and political strikes – like against pension policy in France – are forbidden. It’s a collective bargaining model designed to prevent strikes if both sides act sensibly.

Yet, the gefühlte Realität (perceived reality) suggests there’s Stillstand. Hardly a week passes without news of a strike, disrupting the way to school, to work and – worst of all – holiday plans. The escalating frequency is also taking a toll on the entire economy.

As for Deutsche Bahn (DB), whether there’s a strike or not doesn’t really matter: trains rarely arrive on time anyway. Only about 65% of long-distance trains are pünktlich, according to DB statistics, and their definition of punctuality allows for a six-minute delay.

In addition, 40,000 trains that failed to reach their destination were conveniently omitted from the statistics. Surely it’s just a coincidence that this aligns with the managers’ bonus targets.

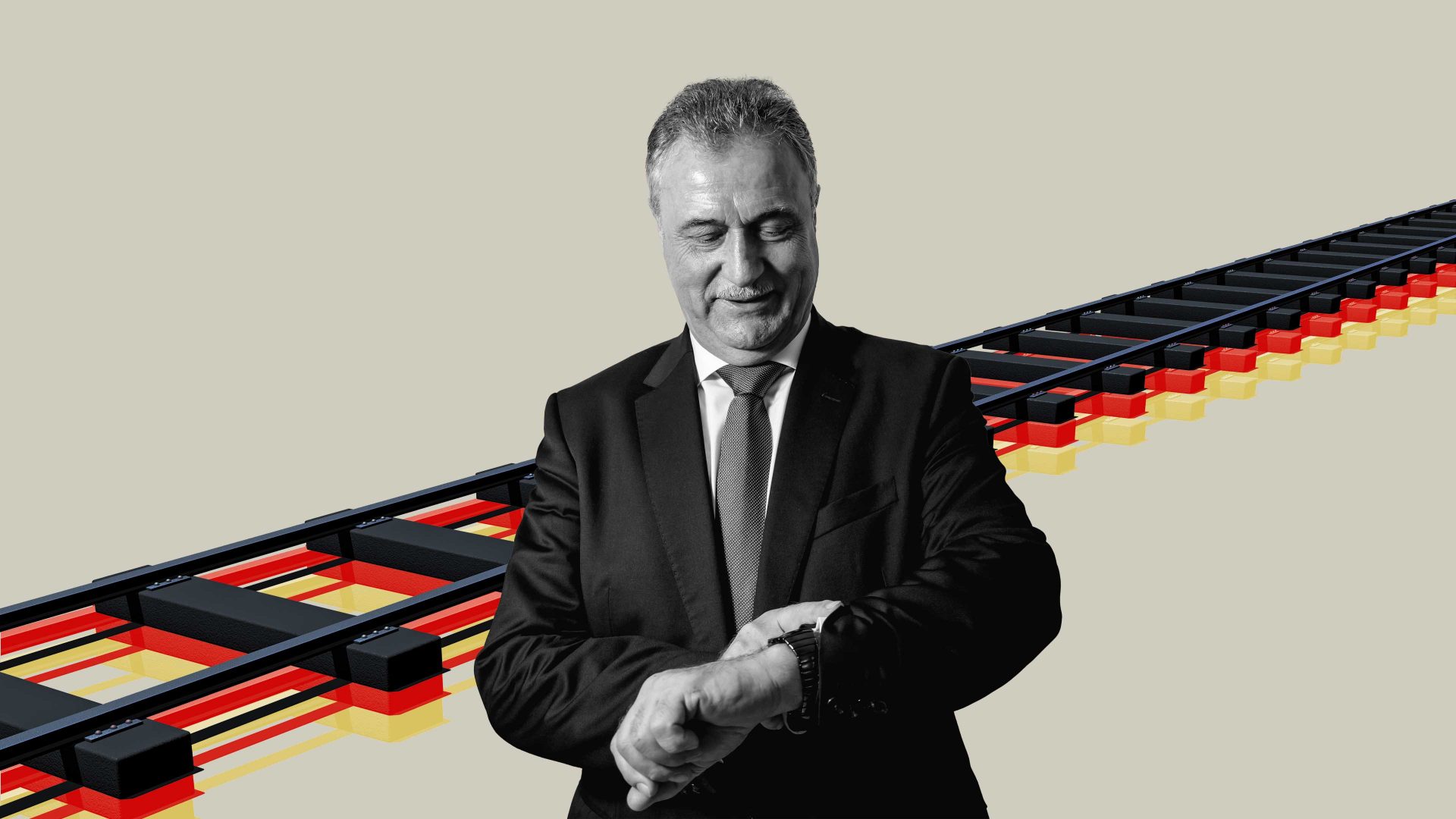

Enter Claus Weselsky, the chairman of the train drivers’ union GDL. A former Lokführer himself (there are innocent meanings to Führer, you know), the 65-year-old from Dresden is on his final mission before retirement.

For 15 years he’s been accused of extortion, of taking commuters hostage and embarking on an ego trip. His union (40,000 members), albeit smaller than the train union EVG (180,000 members), holds significant leverage: no trains run without drivers.

Weselsky’s critics allege that he abuses this power. He in turn criticises DB managers for using chauffeured limousines instead of waiting for the train. And even those feeling bullied by his tactics begrudgingly admit he has a point: DB has been underfunded for 30 years, neglecting customer needs at home and running up debts to turn into a global player.

With railway infrastructure in desperate need of modernisation, people wonder why the German national railway is operating a freight line in Uruguay.

Uruguay’s lack of a border with Germany prevents it from emulating the Swiss approach: Switzerland halts ICE trains at the German border if they are not punctual. Strangely, the Swiss still define “on time” as “on time”, without our six-minute grace period. Passengers must disembark at the German station Basel Bad Bf and take public transport to Basel to continue within the Swiss system.

Mr Weselsky loves this: “It’s great that a country is showing a clear edge, saying: ‘We’re not going to let German unpunctuality wash into our system 20 times a day.’”

In all fairness, Swiss rail receives an average funding of €450 (£385) per capita, German rail only €114 (£98) despite our network being seven times longer (33,500km). The disparity underscored Weselky’s argument that an underfunded DB places undue stress on drivers and staff. Consequently, he demands a monthly raise of €555 (£474) and 35 instead of 38 working hours per week without a pay cut. The Bahn’s proposal suggested a pay raise and 36 hours (a substantial concession given the shortage on the labour market), which was rejected by the union.

A nationwide rail strike costs around €100m (£85.5m) a day. Typically, employees saw off the branch they are sitting on if they overdo industrial action. But state-owned DB can sustain indefinite losses, ultimately shouldered by the taxpayer. Weselky knows this, and has now overdone it: he declared that the next strikes will not even be announced in advance.

If Germany’s most headstrong union boss doesn’t get out of his corner, you yourself may witness German travel chaos during Euro 2024… for as long as you are in it, that is.