In the realm of stereotypes, you may have come across the notion that German speakers are not typically hailed as the most passionate individuals. And, admittedly, we ourselves acknowledge that we are no match for the French or Italians. Nevertheless, there is one area where we demonstrate remarkable zeal: the pursuit of plagiarists, particularly those adorned with a doctoral degree.

While in the UK you have your MBEs, CBEs, OBEs and your right honourable gentlemen and ladies, we boast Doktor iur (law), Dr ing (engineering), Dr rer nat (natural sciences) and so on. Remarkably, more than 120 members of our current parliament hold a doctoral degree; that’s about one-sixth of the Bundestag. And some patients won’t step into a doctor’s office unless it says Dr med on the door (despite the nameplate failing to divulge whether the occupant merely scraped a “pass” in their final exams).

In contrast to the PhD, usually pursued by aspiring scientists, the added value of the German and Austrian Doktortitel often comes down to brass plates outside law firms, banks, management consultancies and even on gravestones. For Germans and Austrians, the Dr-something exudes integrity and prestige – it’s basically a customer acquisition tool that accelerates careers, enhances salaries, secures flight upgrades and even facilitates flat-hunting.

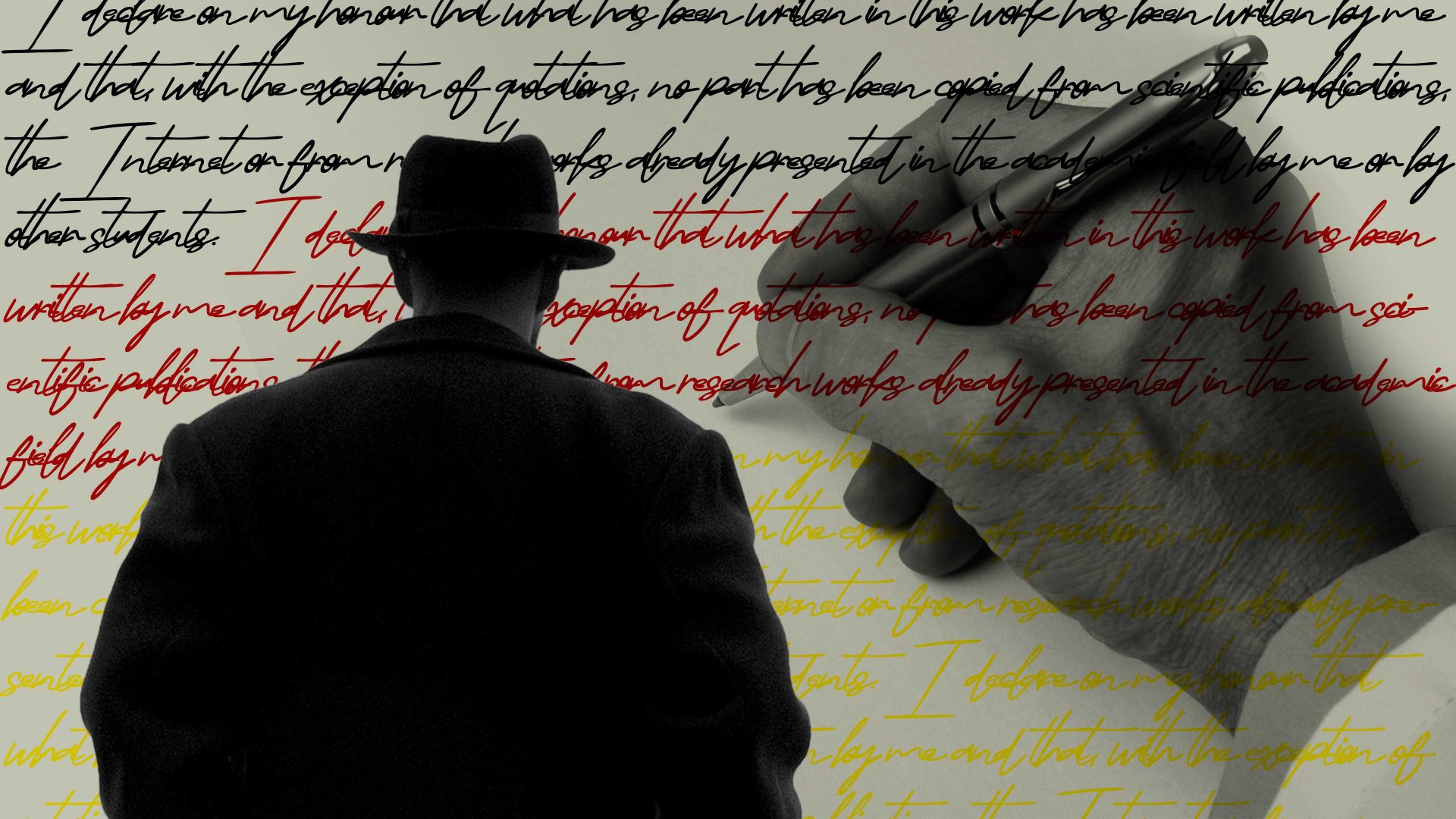

Some particularly cringeworthy specimens insist on being addressed as “Herr Dr”, as legally, the title becomes a part of their name. The underlying rationale behind this Teutonic-Austrian title fetish lies in its historical context: for the lesser, non-aristocratic members of society, it was a way to become respected by the nobility, resulting in a booming market for such degrees in the 19th century. To this day, to deter fraudsters who hire ghostwriters or purchase fake titles from the US, there’s a criminal offence known as Titelmissbrauch (abuse of title).

On the other hand, plagiarism allegations usually unfold in the court of public opinion, with diligent footnote-hunters targeting politicians across genders and political affiliations. Over the past 15 years, several cabinet members have been stripped of their titles – and subsequently their positions. But others kept their degree, citing only minor irregularities, as was the case in 2016 with the now-EU Commission president, Dr med Ursula von der Leyen, and only last month, AfD chairwoman Dr rer pol Alice Weidel.

Personally, I find the Dr hunt a little distasteful. Moreover, considering that academia rather than politics is the biggest playground for plagiarism, it’s surprising how little public attention, if any, scientific misconduct receives. When Dr Angela Merkel’s defence minister’s dissertation was dissected, she was quoted as saying: “I didn’t hire him as an assistant professor.” This remark immediately sparked accusations of playing down dishonesty. When in fact she was just underscoring the insignificance of a doctoral degree for the performance on the job at hand.

Furthermore, should papers from university days, sometimes decades before, warrant public shaming if no further evidence of misbehaviour surfaces? Boston University, for instance, didn’t revoke Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s degree in the late 1980s, despite revelations of improper appropriation in his thesis. Instead, they appended a side note to the book in the university library, listing all the correct citations. Certain achievements transcend the world of footnotes.

This month, another case of “catch the plagiarist” emerged. Interestingly, it involved not a politician, but a journalist. The Austrian deputy editor of the Munich-based Süddeutsche Zeitung, a publication that has often placed itself at the forefront of moral integrity, faced allegations of poaching passages from the internet for her articles. Then an academic bounty hunter joined the stage, claiming that the deputy editor’s dissertation showed signs of plagiarism as well, pledging to scrutinise all her published works.

The battle continued on social media – fair and balanced as usual – when headlines sent shockwaves through the industry: police were searching the river for a woman, presumed to be the journalist in question. Fortunately, she was found ashore beneath a bridge the following day, hypothermic but alive.

Dust will settle on this latest episode eventually. What should (but probably won’t) be remembered is that there are far more important matters in life than the letters preceding our own or other people’s names.