Utagawa Hiroshige was forged by fire and soothed by water. Born in Edo (now Tokyo) in 1797 to a family that was part of a samurai class comprised of civil servants rather than the warriors of old, his destiny seemed written out. His father was fire warden of Edo Castle, a job undemanding enough that the boy could take it over when he was 12.

Then came the flames that burned away the certainty: by the end of the same year, both his parents were dead and Hiroshige (known at the time as Andō Tokutarō) was seeking a life beyond expectations.

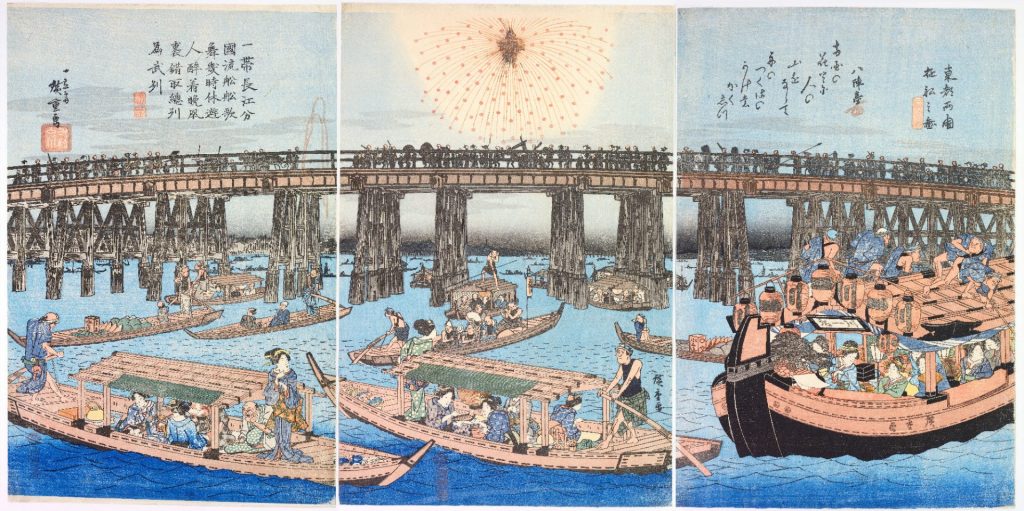

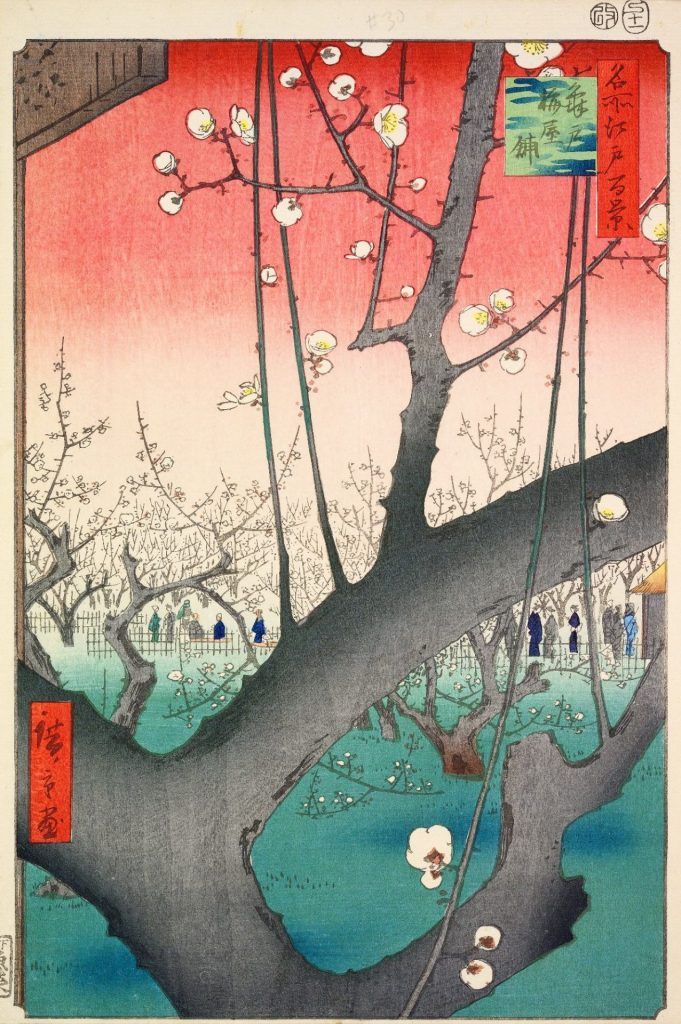

Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road, the book that accompanies an exhibition of the same name at the British Museum, London, details his journey. With his job affording ample downtime – though records praise his “exceptional effort” in tackling a blaze at the samurai neighbourhood of Ogawamachi – but little financial reward, Hiroshige immersed himself in ukiyo-e (literally “pictures of the floating world”), a genre of woodblock prints and paintings popular with the rising chōnin class of merchants and makers. He sought out a mentor in the influential Toyohiro, but arguably his greatest teacher was the land itself.

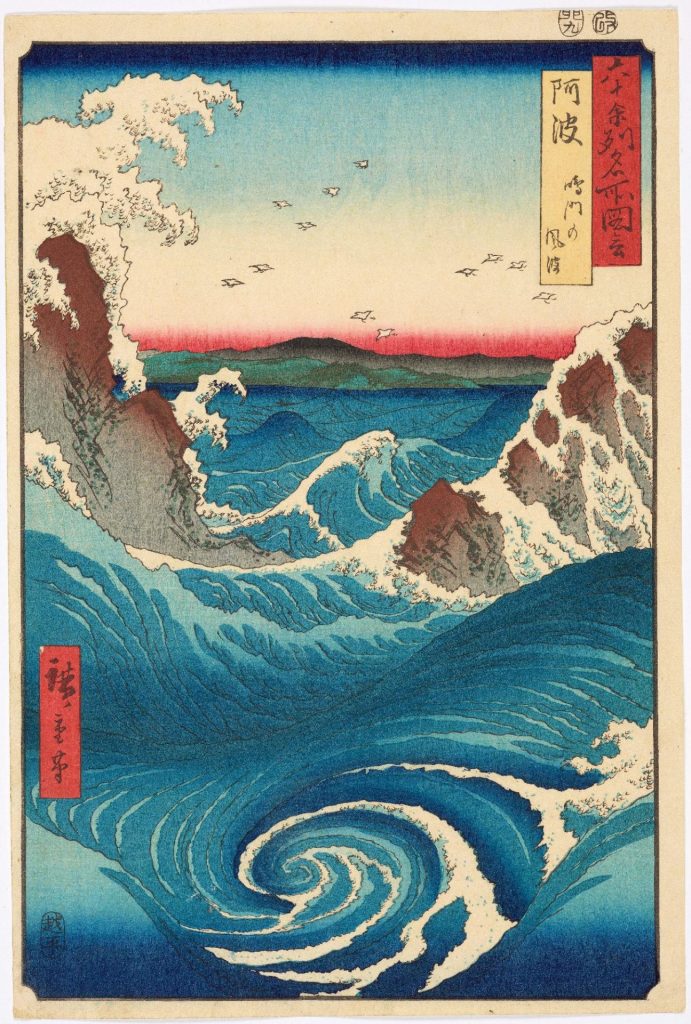

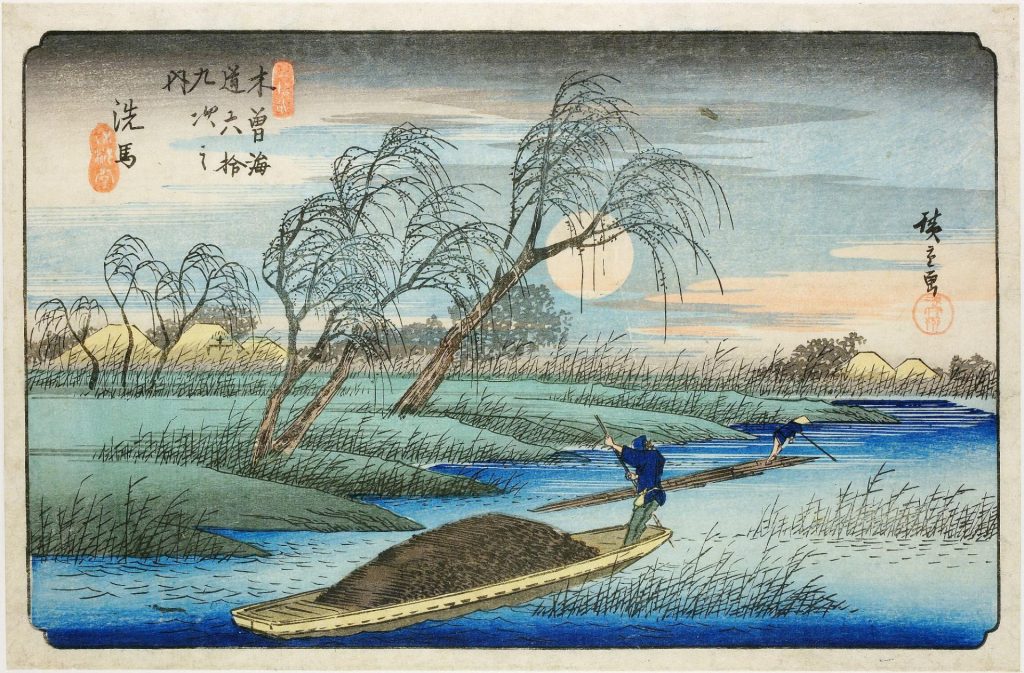

While much of floating world art showcased the daring and decadence of the Edo period with subjects like kabuki performances, sumo wrestlers and beautiful women, Hiroshige captured the natural world as he found it, captivated by the land, the winds and the water. As British Museum curator Alfred Haft writes in the book, he “walked a fine line between documentation and art… Hiroshige was himself a traveller, and drew pictures informed equally by a love of landscape and love of the road”.

The book offers a crisp and intelligent perspective on the sociopolitical currents that shaped his vision, from Edo’s rigid class structure to the phenomenon of domestic travel and pilgrimage. While Hiroshige was adept at capturing a raging torrent, he felt most at home when taking us to places where the chōnin found pleasure – beside streams, ponds and coastal areas. He was aided by the introduction of the vivid pigment Prussian blue to Japan around 1830, adding poetry and longing to his water surfaces and skies.

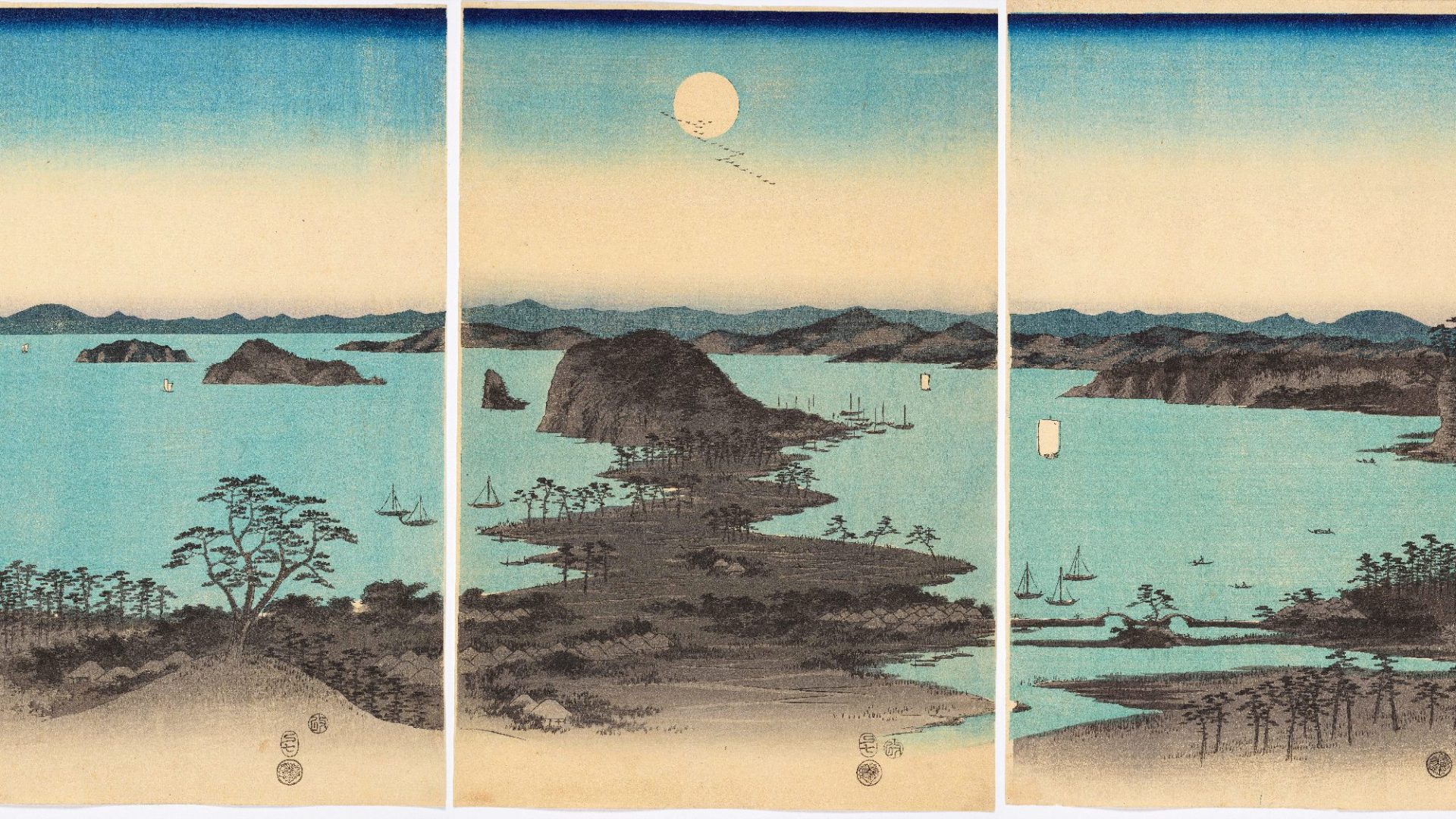

Both book and exhibition show Hiroshige not just as a technician of scenery, but as a chronicler of transience. An early masterwork, Evening View of the Eight Scenic Spots of Kanazawa in Musashi Province, is imbued with a haunting serenity. The distant sails, misty water and descending dusk convey not only place, but a palpable atmosphere, one that Haft calls “a poetry of silence and solitude.” Like many of the others depicted here, it is an invitation to walk beside a master at the water’s edge as he transforms the ordinary into the eternal.

Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road is published by British Museum Books, £40, The exhibition is reviewed by Matthew d’Ancona here