There’s a poignancy about the slightly tubby figure swathed in robes, ascending a ladder which he has somehow conjured out of the clouds. He stretches out to reach a great white globe of a moon, seizes it and hides it in his robes before descending the ethereal stairway.

It is a drawing by the Japanese master, Katsushika Hokusai, and it says as much about creator as the subject. The man reaching for the moon is a practitioner of the Chinese Daoist religion and thanks to his talents he can achieve what is impossible for ordinary folk and furthermore share his gift with them.

So it was with Hokusai (1760-1849) who made his living teaching and sharing his skills and techniques, bringing art to other people with paintings, books and drawing manuals.

And poignant, because like the Daoist in the drawing the artist was obsessed with achieving perfection. Never mind that he was the most successful artist of his day. Not enough that he created 3,000 print designs in his long career and the publication of thousands of works, he was never satisfied by his endeavours.

“At 73,” he wrote. “I began to grasp the structures of birds and beasts, insects and fish, and of the way plants grow. If I go on trying, I will surely understand them still better by the time I am 86, so that by 90 I will have penetrated to their essential nature.”

And he hoped: “At 100, I may well have a positively divine understanding of them, while at 130, 40, or more I will have reached the stage where every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive.”

Now, more than 100 of his drawings made when he was a mere 70 or so years old are on show for the first time at the British Museum – proof indeed that despite – or because of – his longing for perfection he did ‘manage to become an artist’.

The Great Picture Book of Everything is a marvel of wild beasts, prettily plumed birds, ferocious warriors, gentlemen about town, princesses, the poetic and the fearsome, all drawn together to create a realm between fact and fantasy.

So, a marvel – and something of a miracle that the pictures are there to be seen at all. The Great Picture Book was to be his definitive version of the universe yet for reasons that no one can explain the book was never published.

Curator Alfred Haft explains: “We don’t know what happened. Hokusai does refer to completing this kind of project in two letters to his publisher and the drawings were completed and presumably handed over to be compiled into a book but it seems, somehow, to have been put to one side.

“Ironically, the process of making the wood blocks for a book would have resulted in the drawings being cut apart and destroyed in the process. Instead, they remained unused for many years until they were rescued.”

It seems that someone recognised the beauty of the drawings and painstakingly mounted them on postcards and placed them in a specially made wooden box with the engraving ‘The Great Picture Book of Everything, drawn by old man Itsu, Katsushika, the former Hokusai’. (Like many Japanese artists of the era Hokusai changed his name during his career – in his case more than 30 times).

The drawings turned up in the collection of a French collector, Henri Vever (1854–1942) in the late 19th/early 20th centuries and they resurfaced in an auction in 1948 after which they disappeared again, possibly to be kept in a private collection in France.

When the drawings came to light in 2019 they were purchased by the British Museum thanks to the Theresia Gerda Buch Bequest (Buch came to the UK in June 1939 as a refugee from NaziGermany) with support from the Art Fund.

“We are lucky the book was never published,” says Mr Haft. “The result is a catalogue of the universe.”

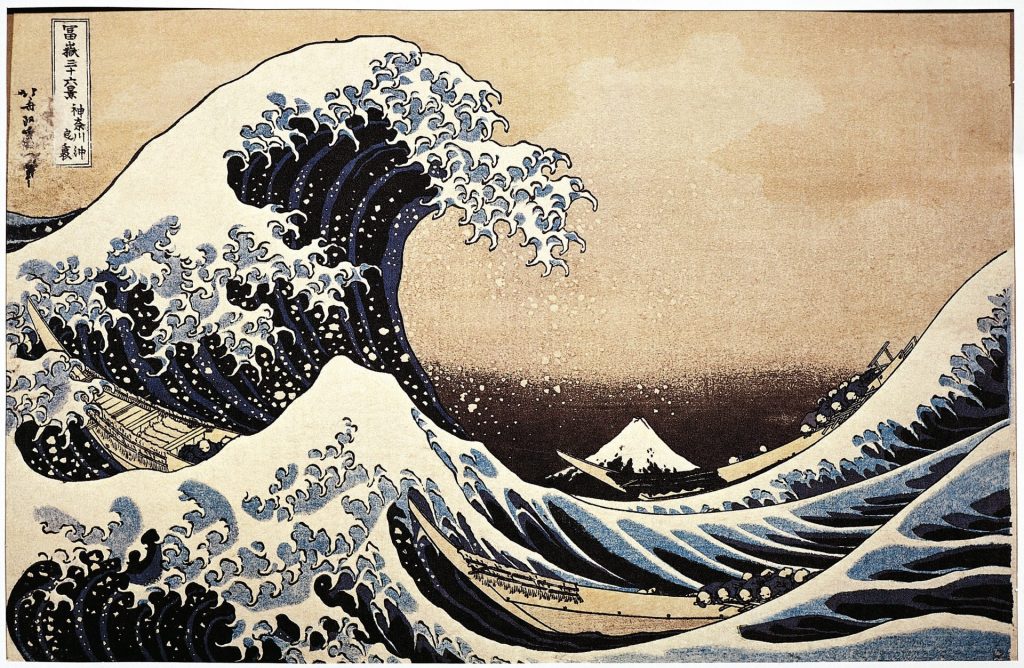

And what a universe. Hokusai is best known for the Great Wave off Kanagawa (c1831) and previously for paintings of the ukiyo-e (‘pictures of the floating world’) with its repertoire of actors, courtesans and erotica. By the 1820s he was determined to bring the entire natural world together in one book.

Encyclopaedias were always popular in Japan, covering subjects as varied as how to run a business, agriculture, the classics and entertainments for children. What Hokusai included and what made The Great Picture Book different was that he added a narrative to the images.

The collection is divided into sections; the natural world – which includes mythical creatures, familiar animals, birds and plants – Buddhist deities, India and its Buddhist disciples, China and foreign lands.

The drawings are made with a delicate touch but often are so complex you have to look hard to follow, say, the curve of a dragon’s tail disappearing into a cave or decipher a bundle of bodies where limbs are so entwined it is hard to see at first glance where one figure begins and another ends.

In the drawings of the natural world, Hokusai embraces every creature he knows as well as some which are the product of wild imaginings. Birds flit across the pages, a bear clambers into a tumultuous waterfall, leopards prowl and a wild boar screams in pain when shot by a hunter.

Porcupines, neighing horses, camels, goats and cats, the animal kingdom is here.

And there are some creatures which have never walked the earth such as the single-horned, cloven-hoofed creature, with spikes on its back, five horns, nine eyes and a face like an old man – an auspicious creature apparently which appears when there is virtuous ruler on the throne. A rhinoceros, drawn purely from the imagination or perhaps from an ancient tome, with a scaly shell like that of a tortoise on its back and three horns confronts a ‘shark person’ which is said to enter a fish by its mouth and gnaw away the intestines. Meet the mythical kashimashidori which cries like a magpie has four wings, a dog’s tail and a single eye.

Hokusai had to rely on his own inventiveness for his creations because Japan under the regime of the Edo endured a policy of isolation from the rest of the world from 1603 and 1867.

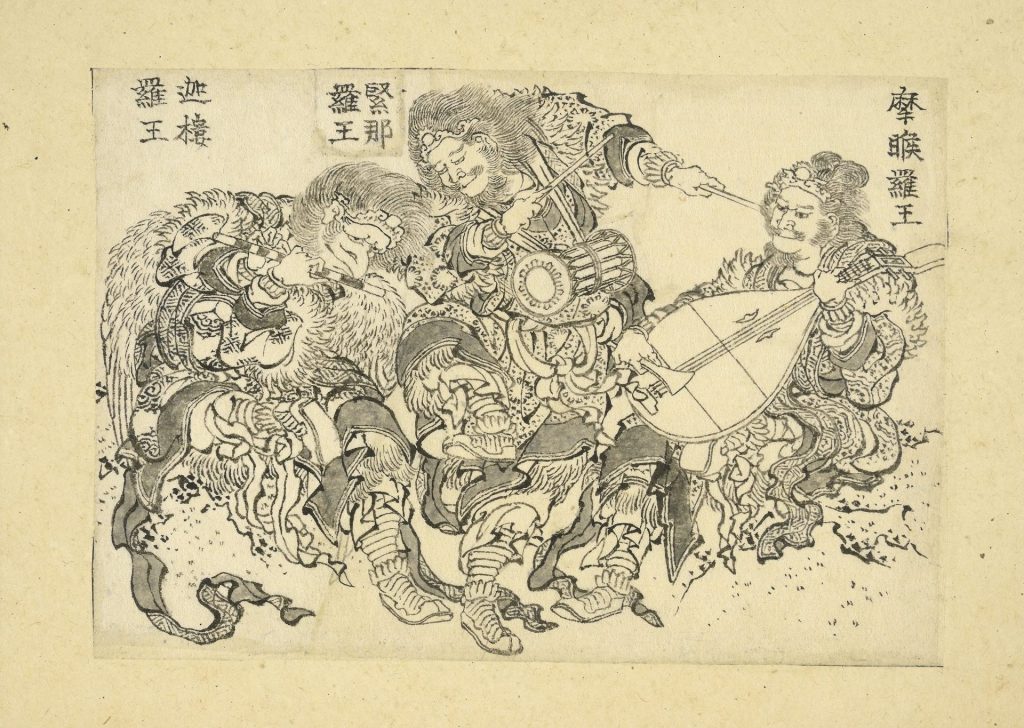

It’s that inventiveness that he brings to his portrayals of Buddhism in which the protagonists are seen teaching, talking and making music. A trio of ‘Protectors of the Buddhist Faith’ disport themselves, one on a lute, one on a drum and another plying a flute. Another group, ‘the Dragon Kings’, read from the scriptures, a lute is strummed and one carries what looks like a plate of pies or fruit.

A ‘God of compassion’ appears seated thoughtfully on the head of a beetle-browed dragon, whose huge tail swoops around the seated god.

Japan had no direct links with India but Hokusai often represented the people as having curly hair and whiskers – like the man apparently cutting up slices of mummified flesh to offer a chief in a bowl. As Hokusai’s notes explain there was a strong belief in the medicinal qualities of flesh which had been mummified in honey.

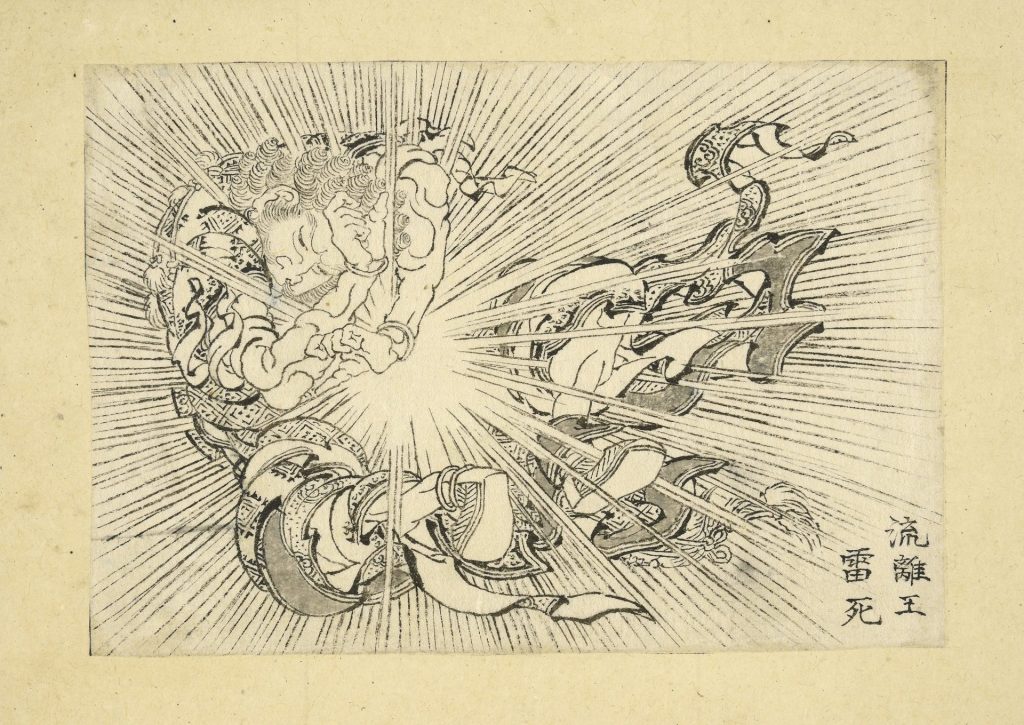

A Buddha disciple conjures up a poisonous dragon from a cave, while another holds a scroll to tempt a nine-tailed fox spirit to emerge from the clouds and there are spirits who take the form of beautiful women to cause mischief. Few have greater impact than the king who was killed by a lightning strike during a celebratory victory banquet. Rays shine out from front, side and back in an almost 3D effect as he is knocked off his feet.

It’s not too fanciful to see shades of Roy Lichtenstein’s Whaam! here and easy to identify a precursor to manga art, comic books and graphic novels, which became popular in the late 19th century.

Despite the isolationist policy, China was the biggest influence on Japan and Hokusai renders what he imagines are typical, rather endearing, day to day scenes of Chinese life. Two men balance a large rock to crush a bag of rice while a third squirts the liquor into a channel but to ensure the job is done properly they add the weight of their own bodies. In his quest to teach, he gives a glimpse of the technology of the day with a group who are measuring grain, filing the teeth of a saw, using a balance for weighing and a plumb line for carpentry.

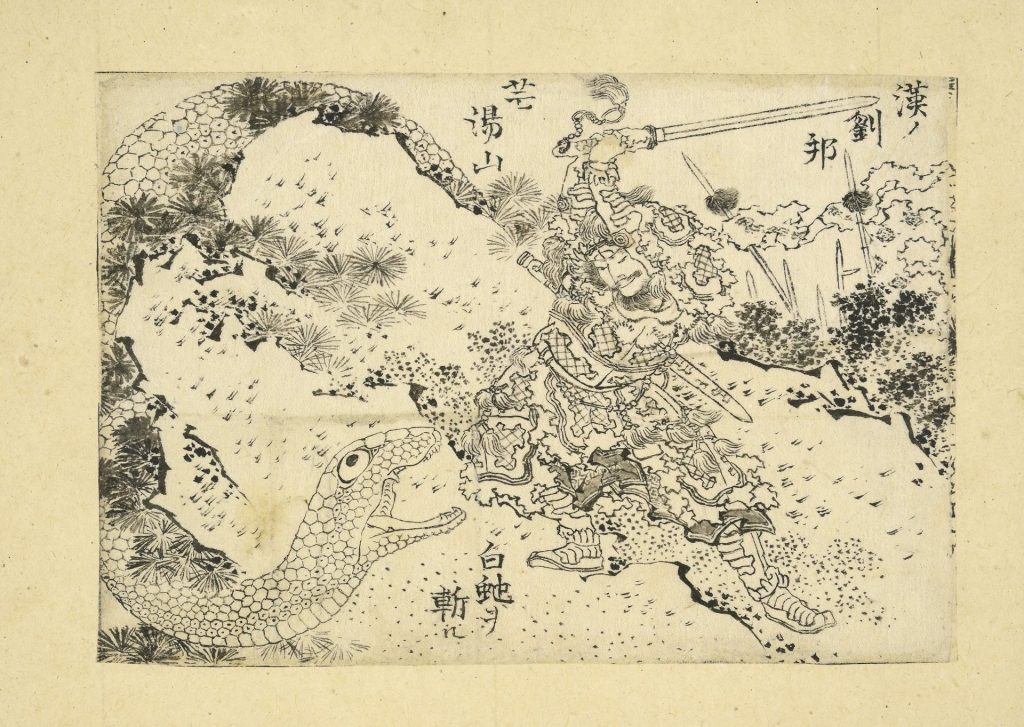

In recognition of its supremacy in the region, there are scenes of Chinese military prowess; an archer shoots nine suns out of the sky so one only remains for the benefit of humanity and in another the founder of the Han dynasty, a drunken Liu Bang (256-195) savages a giant white serpent which had been marauding his outlaw band with a mighty sword.

By way of contrast, a gentle scene of homes and trees fade into distant, wooded mountains in which, high up, almost impossible to pick out so slightly is he drawn, a Chinese general plays a bamboo mouth organ so plaintively that the enemy are stricken with homesickness and leave the battlefield.

Hokusai’s characterisations of men from foreign lands are presented on pages divided into three and present what he thinks they must look like, bewhiskered and be-robed, with strangely beatific expressions. He shows what a man from Vietnam might wear, a fellow from Korea or a ‘Southern Barbarian’, as he called Europeans. They strut, the pose, they carry a bow and arrows, a spear or a sword.

But we are never far from his world of weird imaginings – in his fantasy foreign lands there is a hunch back, a man with arms twice the length of his body, a barbarian whose head flies away from his body as if on elastic, short people, tall people, the ‘land of the winged race who dive into the sea, catch fish and eat it’.

Imagination, skill, drama, all in a postcard. Like the man grasping the moon Hokusai gives his audience a glimpse into a world they would never otherwise have known.

As he writes the titles to some of this work, he explains how he is: “Receiving from the gods and sharing with open hands.”

Hokusai: The Great Picture Book of Everything, British Museum, until January 30, 2022. The accompanying book by Timothy Clark is published by the British Museum, £25. It is cleverly produced so that every image is reproduced in the actual size of the original.