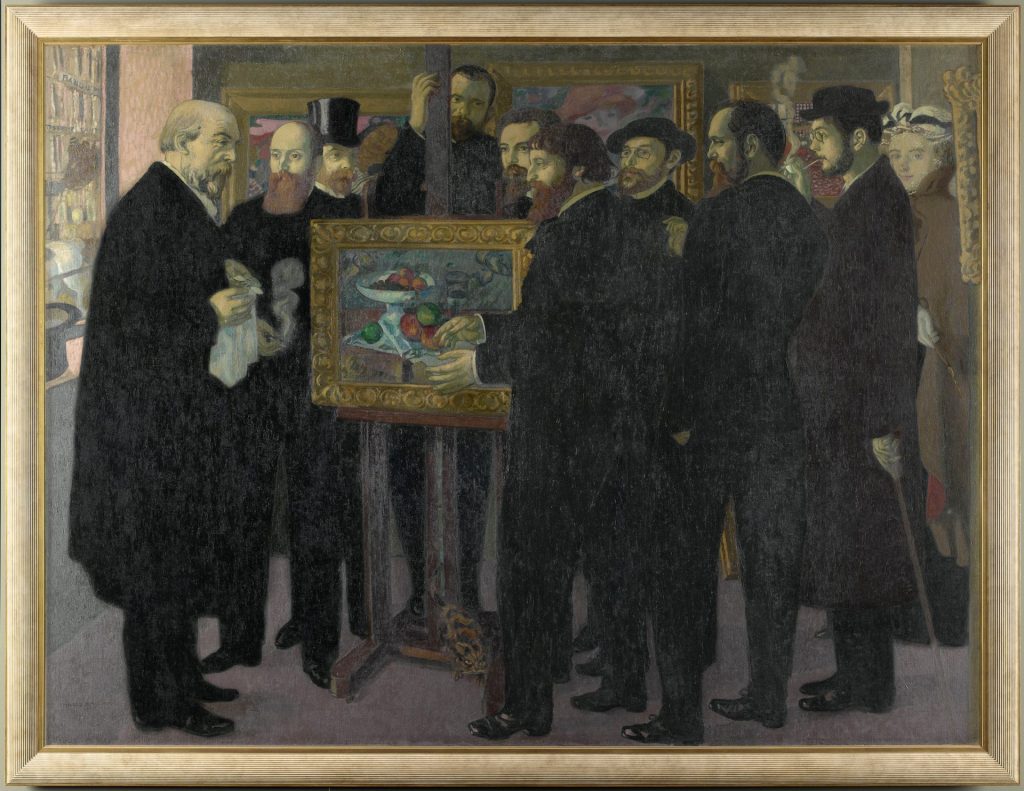

Lowering her lorgnettes, Marthe Denis turns away from the committee-like group of men who are admiring a still-life by Paul Cezanne. A moment later, Marthe might have rolled her eyes at us, in a mixture of exasperation and affection. “All these bearded men! All these pictures! All this talk!” she seems to say, as she stares out at us nonchalantly from Homage to Cezanne, painted by her husband, Maurice Denis, in 1900.

In the preceding decades, the fine art mould had been broken by the Impressionists, and the successors of those pioneers had each to find their

own purpose amid the scattered pieces of the old orthodoxy.

Denis’s bearded line-up of art viewers, solemnly gathered around Cezanne’s portrait of a fruit bowl and cloth, is normally on display at the Musée d’Orsay. Once owned by the writer André Gide, Denis’s painting shows the moment when the French avant-garde broke ranks with the country’s fiercely conservative classical tradition. Among those depicted in the painting are the symbolist painter Odilon Redon and Édouard Vuillard, the decorative artist, painter and printmaker. Denis’s career took him towards religious art, which he set in a modern-day tableau. In one painting, he depicted Marthe as a Virgin Mary for the new century as she cradled her baby, with a modern-day Elizabeth and infant John the Baptist looking on.

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art at the National Gallery in London tells the story of how fine art changed beyond all recognition between 1886 and the outbreak of the first world war. Liberated from the studio by the availability of ready-mixed, portable paints, Cezanne, Monet, Renoir and others shook off expectations of subject matter, use of colour and form.

Where could they go? The answer, in part, was Europe, or at least its principal cities and landscapes. Paris, of course, whose magnetic pull at the

beginning of the 20th century drew the young Pablo Picasso from Spain and fragile Amedeo Modigliani from his native Italy. But also Brussels, Barcelona, Vienna and Berlin, the distinctive tone of each city informing the art.

The artistic horizons of the time were expanding, but nevertheless, Cezanne (1839-1906) cast a long shadow across the whole continent. His flattening of the image, frank experiments with colour and his abandonment of perspective did not stop at the fruit bowl on the tabletop. In one painting, Madame Cezanne in a Red Dress, we see his wife – Marie-Hortense Fiquet – flat as a board, boneless inside her dress, perched on a chair that occupies the same plane, alongside a thick, bunched but depthless green curtain.

Picasso and Henri Matisse saw Cezanne’s famous bathers with their rigid backs, helmet hair and accompanying geometric dog in an exhibition held in 1907, a year after Cezanne’s death. Both men promptly painted bathers of their own. Theirs was a relationship of uneasy respect, not uncommon among the strong characters of the art world. Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin worked alongside each other in 1888, then fell out over faithfulness to nature (Van Gogh) and invention (Gauguin). But in that year both produced arresting pictures. In his Mas a Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, Van Gogh sets a yellow sky above blue roofs.

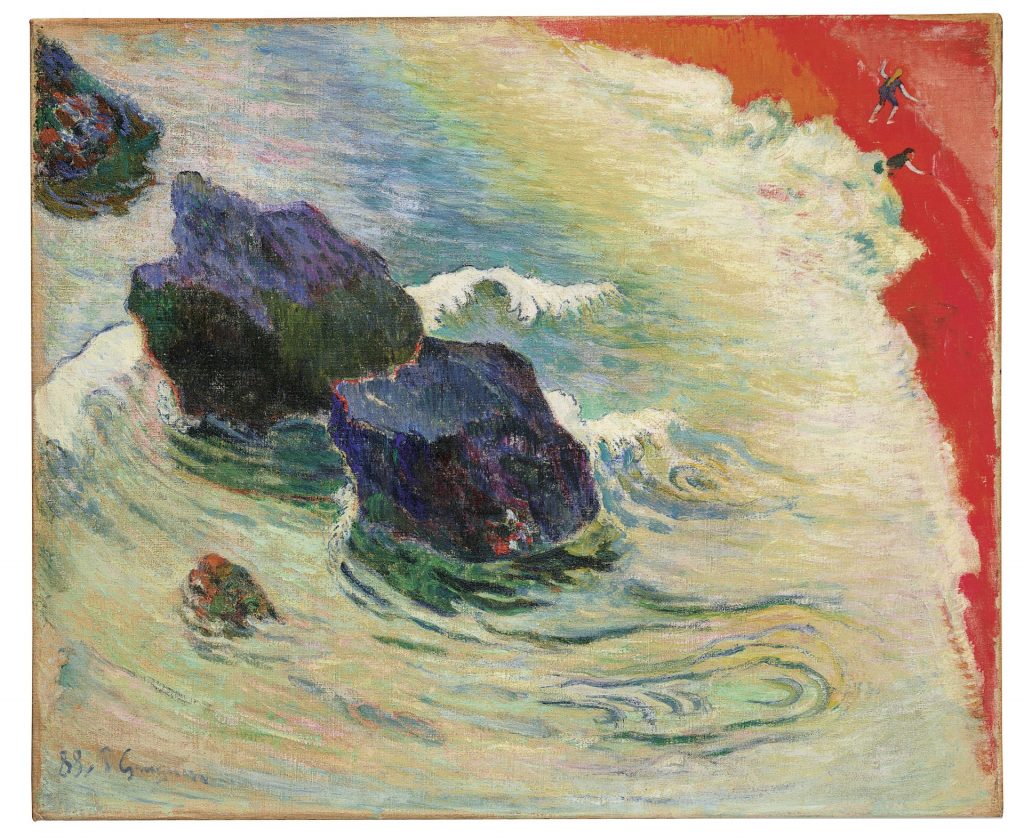

Gauguin, too, was finding colour in unexpected places. In The Wave, the beach is an alarming red colour, as the bathers scramble to shore. It was not

only fellow Europeans who were influencing each other: The Wave recalls the Japanese woodblock prints that Gauguin admired and collected.

But for all the innovation of colour, the unconventional training of some artists, the dispensing with perspective, the celebration of formerly ignoble subjects, there is one clear boundary – the glass ceiling. With only a handful of female artists in this celebration of 30 years of radical art, you have to wonder where half the population has gone.

If many paintings’ subjects are anything to go by, the answer, predictably, is home. Sewing, minding the baby, playing the piano, lounging, bathing… Women as depicted by this go-ahead group are depicted as anything but go-ahead themselves. If they live at all, that is. Edvard Munch, haunted always by the death at the age of 15 of his older sister, Sophie, often returned to her side, as in Death Bed (1895). Men and women alike are helpless as life ebbs from the piteous little form beneath the blankets.

Nudity is still the dress code for many models. The exception to this surprisingly traditional or regressively negative imagery is the daring young

women in a huge painting by Ramon Casas, an artist from Barcelona. In The

Car, painted in 1900, she laughingly drives her car – yes, drives, and is not driven – straight at us, leaving an open-air concert. But notice, it is the machine rather than its nameless female driver that gets top billing.

Of the show’s female painters, two, Käthe Kollwitz and Paula Modersohn-Becker, have recently been the subject of the Royal Academy’s Making Modernism. At the National Gallery, Modersohn-Becker’s Old Peasant Woman, painted around 1905, rejects youth, conventional beauty and social status in one dignified portrait. The figures in Kollwitz’s sculpted Pair of Lovers are ambiguous: are both even alive?

But there are so many other female artists who broke the mould in their own way. So, let’s welcome to the party Broncia Koller-Pinell (1863-1934). Born Bronislawa Pineles in Sanok, then in Poland, she trained in Munich and Vienna, where, by the age of 25, she was exhibiting. Her friendship with Gustav Klimt is manifest in the decorative elements of her striking portrait of 1907, The Artist’s Mother. Its golden background and stylised flowers belong to the early 20th century, but the image is timeless, the older, black-clad woman concentrating intently on her handiwork.

Koller-Pinell was at a double social disadvantage as a woman and a Jew, but she exhibited constantly throughout her life, and was in the vanguard of Egon Schiele’s pre-war Neue Secession, a short-lived Expressionist movement whose members included Gabriele Münter and Marianne Werefkin – female artists also recently celebrated alongside Modersohn-Becker and Kollwitz, but not here.

Outliving even Picasso, poster boy of the modern age, Sonia Delaunay (1885-

1979) took the name of her second husband, Robert Delaunay, with whom she developed Orphism, a painting style that combined the fragmentation

of Cubism, the colour palette and energy of Fauvism and the movement of Futurism. She was only in her early 20s when she painted her Young Finnish Woman (1907), with its radical and daring blues, greens and oranges in the model’s complexion. No wonder she went on to design wondrous fabrics and clothes.

The Delaunays, the Matisses, the Denises… Modernism proved no match for marriage, but friendships and fallings-out alike were also propagated in the fertile landscape of anything goes. Matisse invited André Derain to join him in Collioure in the Languedoc, where he lived in 1907. Here they too experimented with colour. “When I put down a green, it doesn’t mean grass,” says Matisse squarely, “and when I put down a blue, it doesn’t mean the sky.”

Landscapes, portraits, conversation pieces… there is not much sign yet of the accelerating industrialisation or social upheaval that came with it, even

though, 10 years before the time span of the exhibition, Claude Monet had

enveloped himself in steam at the Gare Saint-Lazare and, in Spain, Joaquín

Sorolla ended the 19th century with a series of searing insights into social

deprivation and working-class lives in peril.

The exhibition closes with the artists who, after the shifting sands of the 1880s to 1910s became and remain the monolithic rocks of the 20th century: Picasso and Matisse. The infallible composition of the former and the untouchable colour instincts of the latter may have evolved in tandem with the explorations of others, but these two showed the way ahead, through Cubism, and beyond. Both artists were also impressed by the art of non-European countries. Picasso collected the masks that were raided from French colonies and traded in Paris. Matisse, who grew up with a feeling for textiles, treasured weavings and hangings from other cultures. Amélie Matisse wears a kimono in a portrait by Derain from 1905, which like many others in the show comes from a private collection. Pictures rarely or never

seen are one of the pleasures of this show.

Perhaps it is works by the Dutch-born Piet Mondrian that best illustrate the giant steps from figurative art to abstraction. Three canvases, hung together, point the way, and that linear way is vertical, or horizontal. A single tree in 1906 morphs within six years into a grid, which will itself become simplified in the ensuing years. First there will be war, and a reversion to classicism, before the acceptance of pure abstraction. But that’s another story.

After Impression: Inventing Modern Art is at the National Gallery, London, until August 13