In June last year, a promising 17-year-old defender named Cathal Heffernan moved from his hometown football club, Cork City, in the League of Ireland, to AC Milan

This was an unusual move, not just because Cork to Milan is such a great footballing leap, but because until relatively recently young Irish footballers would have a much more well-worn path. A promising player might move to Liverpool perhaps, or Manchester United, maybe even Burnley or Barnsley.

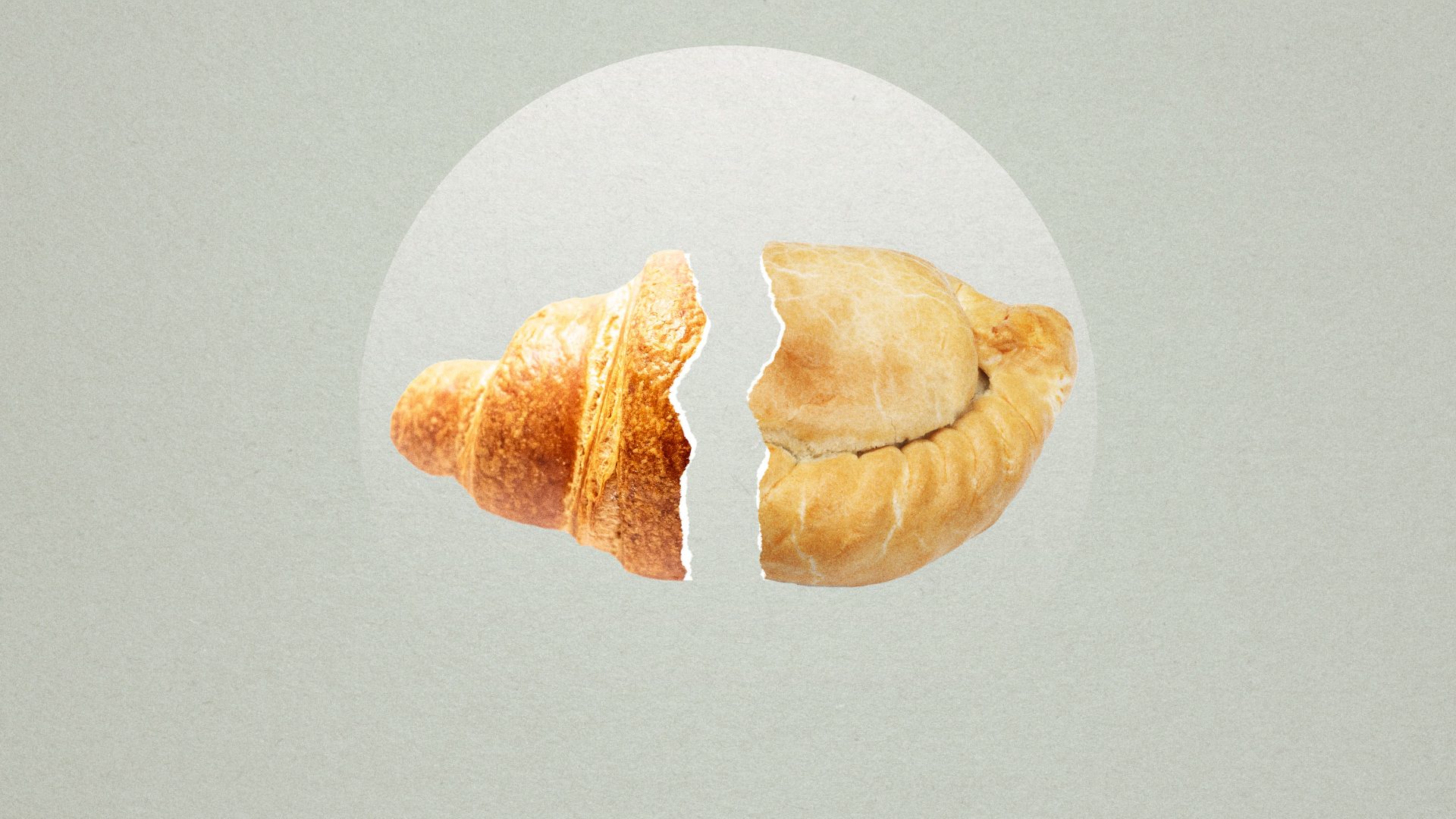

But when Britain left the EU the rules on football transfers changed, particularly when it came to young players, so that English clubs could no longer sign the cream of Europe’s emerging talent from across the continent. The end of freedom of movement has made it difficult for clubs to buy in all but the most elite of European players. When another talented young Irishman, Kevin Zefi, signed for Inter Milan from Shamrock Rovers at the age of 16, Italy’s La Gazzetta dello Sport knew what to thank. The players had arrived, read the headline, “grazie alla Brexit”.

“There’s no longer this transfer of players, or movement of players,” Arshia Hashmi, a senior associate at law firm Brabners and an expert in sports-related immigration issues, tells me.

“They can still move within the EU, but as we’re no longer a part of that, we’re actually a little bit disadvantaged. There are now restrictions on under-18s coming into the UK, so that’s put UK clubs out of the market for those players that are aged between 16 to 18.”

Had these regulations been in place previously, players who would not have come to the Premier League include Cesc Fabregas, Nicolas Anelka and Hector Bellerin, all at Arsenal, and Paul Pogba in his first spell at Manchester United. As the rules also work the other way around it would have prevented Jadon Sancho and Jude Bellingham from making their moves to Borussia Dortmund. And it means that, by the time players are eligible to move to England, they are more experienced and thus expensive, if not already in the clutches of the elite clubs of Spain, Germany, Italy and France.

And that’s not the only effect of Brexit. Prior to Britain’s departure, EU footballers enjoyed the same freedom of movement of anybody else, allowing them to pick and choose where to play. But now they require a work permit, and to prove they’re good enough to warrant one, they have to satisfy a convoluted points system devised by the FA in England.

“They effectively need to score 15 points in order to attain a governing body endorsement – so that’s an endorsement from the FA to say that they are highly-skilled, they are elite in what they do and they will make a significant contribution to football in the UK,” explains Hashmi.

“There are different criteria, so some of them depend on what country they’ve played for, the level of club that they’ve played for, the number of matches that they’ve been involved in. That’s where the difficulty lies. Previously, younger players may have been able to meet that. Now we’re out of the market between 16 and 18. Actually they may well be playing at a higher level overseas, which means when it comes to a governing body endorsement it means that clubs are potentially having to pay more because that player is now advanced in their career.

“In terms of the 15 points, it works off the FIFA world rankings in terms of the top 50 countries that are there, so the lower down the list of that top 50 that you go the less points that you get. So there are some countries where, ultimately, just because you’ve played for their national team it’s an ‘autopass’, which means straight away – 15 points, you’re in.”

Probably the most high-profile of the transfers that fell through due to the new rules was that of Justin Kluivert, son of the former Dutch international Patrick, who Fulham attempted to sign from AS Roma in August 2022. His lack of game time at the Italian club counted against him. Another forward, the Spaniard Diego Costa, initially had his work permit application turned down when signing for Wolves in September 2022, but he successfully appealed to the FA’s exceptions panel.

That panel, Hashmi explains, “is there to consider where cases fall short of 15 points, but the club or the individual is arguing that there are exceptional circumstances.”

Unlike the pools panel or the Dubious Goals Committee, however, this is not a group of ex-pros watching YouTube clips of the players over an agreeable lunch. Instead, there are three people – one legal expert and two with a “significant experience at the highest levels of football”.

“There isn’t much information in terms of the types of exceptional circumstances that the exceptions panel will cover,” says Hashmi. “There are a handful of examples given within the FA’s guidance which is more around if, for example, due to injury they were unable to play certain matches but the club can demonstrate that, had they not been injured, they absolutely would have played those matches, then that is something that the exceptions panel can take into consideration. Then what happens is the exceptions panel will make a recommendation to the FA, but ultimately it’s the FA that has a final say as to whether or not they accept that recommendation.”

Adrian Bevington was the FA’s Club England managing director from 2010 to 2015. He told me that the league most acutely affected by the rules changes was not the Premier League.

“There’s no doubt about it. Brexit has certainly made the transfer market more challenging in England, and I would say particularly in the English Championship,” he says, referring to England’s second tier.

“Players who are at the Premier League level are generally playing in top divisions or internationally, or both, or in European club competition before they go to the Premier League, so they qualify with 15 points.

“But look at clubs historically, in the past decade, who have been very good at acquiring talent, say, out of Ligue 2 [France’s second tier] in France as an example. They wouldn’t necessarily qualify now, because they wouldn’t be playing European club football, they may not be internationals, and if they’re playing Ligue 2 in France they wouldn’t get in. It’s made the market a lot more difficult to get the players from EU countries into clubs which would historically have got them in the Championship or maybe League One [England’s third tier].”

One unexpected side-effect of the changes was that, while it is considerably more difficult to sign players from within the EU, it has become easier to buy them from leagues in Latin America.

Says Hashmi: “What we have seen is the FIFA rankings and the bandings, they were altered slightly, adjusted slightly just before Brexit, and that has made it easier for people from certain countries to get that [eligibility] and get points awarded.

“In terms of the markets that have opened up, we’ve seen a shift in the points available in, for example, Argentina, Mexico, Brazil – so leagues in those three countries, their rankings have now been adjusted… so you can get more points playing in leagues in those countries compared to pre-Brexit.

“I think we will only see the real impact of it a couple more years down the line. The FA have quite openly said just before Brexit that they would be keeping the GB criteria under review.

“When the recent paper was released in terms of the governance of football, the football white paper on regulating the sector, there was also an announcement by ministers that they were going to review the efficiency of the existing visa system with the goal of attracting the best global talent to English football.”

Meanwhile, the biggest clubs can use their financial clout to buy or form ‘sister’ clubs or academies in other parts of the world and perhaps park players who are too young or as yet unable to gain a work permit for a few years. Manchester City, for example, is part of the City Group along with New York City, Melbourne City, Spain’s Girona and Belgium’s Lommel SK, among others, while for a long time the Netherlands’ Vitesse Arnhem was a reliable loan destination for Chelsea’s fringe players.

“I think the investments we’ve seen from UK clubs into overseas football is quite telling,” says Hashmi.

“City Group’s investment allows them to build up academies and clubs overseas that can then harness the potential of youth players. It allows them to ensure that the overseas clubs and academies are aligned with City Group’s main objectives here in the UK, and actually I think that’s quite telling in terms of the more investment that’s being put in by UK clubs into overseas football. It’s allowing them to almost shape and mould youth players so that, when they are ready for transfer at the age of 18, they have already played in the right type of games, they’ve already played at the right level, because there has been the synergy between the UK club that’s investing and the clubs or academies that they’re investing in.”

But this sort of deal, she acknowledges, is not really an option outside the biggest clubs of the Premier League. And, as Bevington says: “The Championship clubs generally don’t have the partnerships in Europe where they send players out.”

And further down the football pyramid, the cost and bureaucracy could be off-putting.

“In terms of being able to bring in an overseas player, the club needs to have a Home Office sponsor licence,” says Hashmi. “To be able to do that they’d then have to pay for the certificates of sponsorship to assign to that player. If the player doesn’t meet [the eligibility criteria] and they go to the exceptions panel, there’s a £5,000 fee to have the application considered.”

But couldn’t that be a positive thing – giving young English, or British, talent more opportunities to get game time and develop?

“From a development point of view it definitely should create more opportunity,” Bevington says. “What you would counter that with is the balance.

“I think every club in the Championship has become better with their recruitment profiling over the past decade into territories that are now maybe not as easy to get players in. So I gave you the French Ligue 2 as an example, but there are many other examples there.

“The Scottish Premier League is now a market that’s scouted a lot more than it was previously, in my opinion, and you’ve seen players from Scotland moving down increasingly to England. But actually you’ve also seen some players out of Scotland moving into other countries of Europe.

“I’m working on the player agency side at the moment for an agency that has a lot of players based in Europe, particularly in Germany. It’s an education for a lot of agents around Europe that players who, three or four years ago, would have qualified and been attractive for English clubs, at this particular moment don’t necessarily qualify.”

The view that English World Cup success is being stymied by foreign players in the English leagues doesn’t hold water. Until 1978 overseas players were in effect barred from playing in England by an FA edict that players had to live in the UK for two years before playing for an English side (1956 footballer of the year Bert Trautmann got around it by marking time in a prisoner-of-war camp). But England failed to even qualify for the World Cup of that year, or the one before it.

It’s just another bureaucratic nightmare created by Brexit – and the diminution of one of those few industries at which we still, just about, lead the world. “Grazie alla Brexit” indeed.