GERMANY

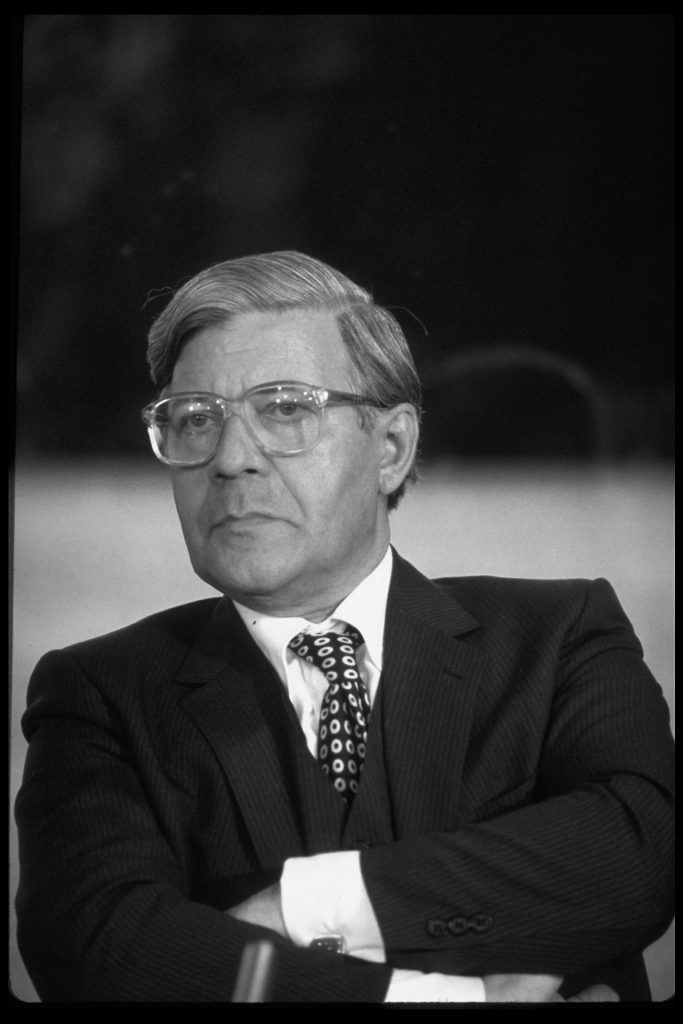

The chancellor can be removed via a “constructive vote of no confidence”. The motion must first be proposed by at least a quarter of the members of the Bundestag and must contain the name of a replacement candidate as the new head of the federal government. The Bundestag then votes on the motion within 48 hours and if a majority of MPs are in favour of the successor, the president appoints him/her as chancellor. This is how Helmut Kohl took power in 1982 – he had convinced his coalition partner to oust Helmut Schmidt.

This process means that there is no leadership vacuum, avoiding the instability found during the Weimar Republic, when parliaments could remove chancellors and ministers at will by motions of no confidence without even having a majority to form a new government.

SPAIN

A prime minister can be removed by a vote of no confidence; the current prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, of the socialist PSOE party, came to power when his predecessor, the conservative Mariano Rajoy, was defeated in just such a vote in 2018 – the first time since the Franco dictatorship and Spain’s transition to democracy in 1975 that a prime minister had lost a no-confidence vote.

Rajoy’s Popular party had been discredited by a massive campaign slush fund scandal – its former treasurer was jailed for 33 years – and, despite Sánchez having only 84 seats in the 350-seat Congress, he won the no-confidence vote by cobbling together a coalition of parties – including the Basque Nationalist party and two proindependence Catalan parties – to get the support of 180 MPs, four more than the 176 needed.

BELGIUM

It is simple to remove a prime minister of Belgium but difficult to become one. The PM comes to office via a complex process further complicated by the fact that the Flemish and French-speaking communities often struggle to agree on candidates.

After an election, the king appoints a formateur, who is responsible for forming the government. The formateur usually becomes PM but the process can take months – in 2010, the country took 541 days to assemble a government.

In 2018, the prime minister, Charles Michel, resigned after one of his main coalition partners quit in a row over migration and a vote of no confidence was proposed. Michel offered his resignation to the king and a snap election was called. Alexander De Croo was sworn in in 2020 after two years without a formal government.

GREECE

The prime minister is usually the leader of the political party with an absolute majority of seats – if no overall majority is obtained, the largest parties take turns to attempt to form a government.

A prime minister and his or her government can be removed through a vote of no confidence. In July 2019, the conservative Kyriakos Mitsotakis took office after winning an election on a pledge to create jobs and boost investment. In January this year, the leftist opposition leader and former prime minister Alexis Tsipras filed a motion of no confidence in the government over what he called its botched response to a blizzard that left thousands of motorists stranded in their cars across the country. Mitsotakis survived the motion, winning with 156 votes, five clear of the 151-vote threshold required in the 300-seat parliament.

IRELAND

If a motion of no confidence in the Taoiseach or the government is passed both the Taoiseach and their government must resign. To remove the leader of a party, a quarter of all its MPs must sign a motion of no confidence. If the Taoiseach resigns as leader of his/ her party to avoid such a vote, a successor is elected – a move that can trigger a general election, particularly if coalition partners do not accept the new party leader.

In 2011, the then foreign minister, Micheál Martin, instigated a vote of no confidence in Taoiseach Brian Cowen’s role as Fianna Fáil leader, but Cowen won the vote. Martin resigned from the cabinet but then, under pressure, Cowen was forced to step down as party leader a few days later. Martin was elected to succeed him, taking over as Taoiseach after a later election.

SWEDEN

When a prime minister, or statsminister, resigns, dies or is forced from office through a vote of no confidence, the speaker of the Riksdag asks the premier or their deputy to stay as a caretaker government until a new administration is formed.

In June last year, the centre-left leader Stefan Löfven became the first Swedish PM to be ousted by a no-confidence motion. However, just weeks later Löfven was re-elected by parliament and he led a caretaker government for six more months before he asked to be dismissed. The speaker then held talks with the country’s eight parliamentary party leaders to decide on a replacement. Löfven’s fellow Social Democrat Magdalena Andersson was chosen, and became Sweden’s first female prime minister in November. Her government narrowly survived a no-confidence vote on June 7.

FRANCE

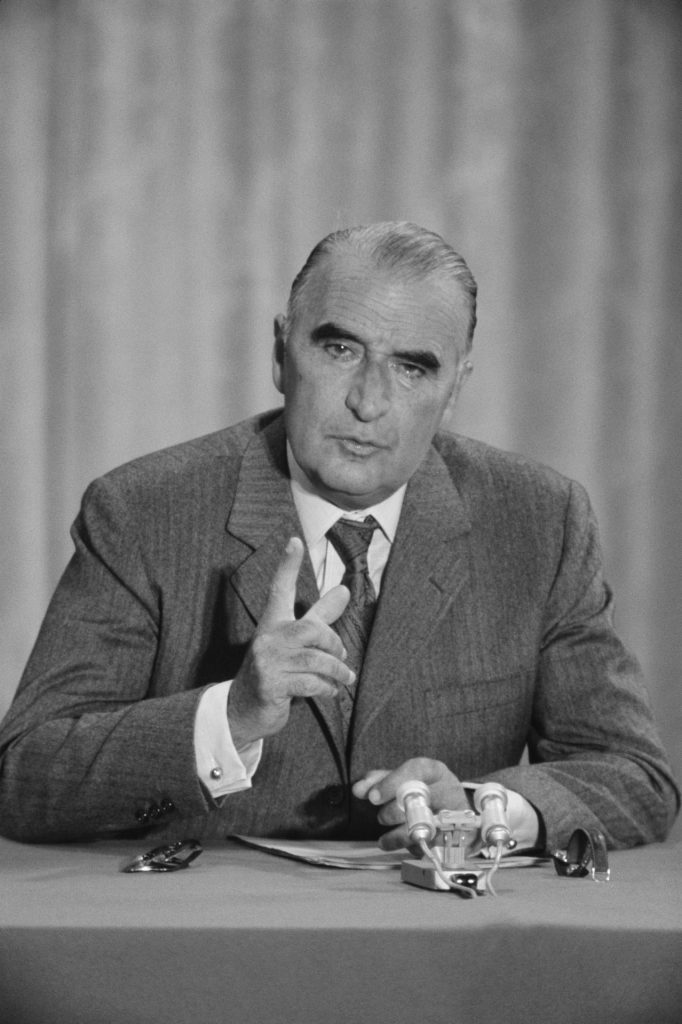

The president of France has a greater degree of executive power than the prime minister and their government and, although not allowed to dismiss the premier at will, can ask for his or her resignation, as well as dissolve parliament altogether.

A vote of no confidence can be brought against the president; in 2018, Emmanuel Macron won one after the Gilets Jaunes protests. Georges Pompidou was not so lucky in 1962, and was toppled. The president can also be removed by impeachment for wilfully violating the constitution or national laws. But in practice, the French political system mostly makes it very difficult to oust a president from office.

The lower house of the French parliament can pass a motion of no confidence in the government as a whole with a simple majority vote.

ITALY

The theoretically symbolic but powerful president is the guarantor of last resort for a stable, competent government. If a prime minister loses a vote on an important bill, one which they have portrayed as a symbolic issue of confidence, even by a single vote, the president will ask him or her to step down. If a ruling coalition becomes unable to push through key policy, the president will ask the PM to step down. The president can sack a prime minister who refuses to leave, but so far the face-saving resignation has been the rule.

Deputies and senators may also move a motion of no confidence in the government at any time, provided it is signed by at least one-tenth of the members of one of the two houses of parliament. Giuseppe Conte won a vote of no confidence in January 2021, but resigned a week later.

POLAND

Polish prime ministers can go in two ways. In 2017, Beata Szydło of the Law and Justice party (PiS), who was popular at home but at daggers drawn with Brussels over migration and the rule of law, easily won a vote of confidence bought by the opposition. But the same day, her own party leader, Jarosław Kaczyński, handed her a large bunch of flowers in the chamber then demanded she resign in favour of the current premier, Mateusz Morawiecki.

The president can dissolve parliament if the leadership loses a confidence vote of an absolute majority of all deputies, or if a draft budget has not been adopted within four months of it being submitted. If a government becomes unworkable, the Sejm or lower house can shorten its term by passing a resolution supported by at least two-thirds of its deputies.

NETHERLANDS

The government falls if one coalition party pulls its support and the remaining leadership cannot form a new coalition. Deputies or the house of representatives may also bring motions of no confidence against the prime minister, who must tender his or her resignation if the vote is lost. Mark Rutte, who has been in power since 2010, has survived several, earning him the moniker “Teflon Mark”.

The first was in 2012, when he promised in the middle of the eurozone crisis that he would give “not one more cent for Greece”. When three years later he supported a multibillion-euro bailout for Athens, he faced a no-confidence vote that he easily won. In April last year, Rutte narrowly survived another confidence vote 78-72 over claims that he lied during lengthy coalition talks.