Many aspects of medicine have confused me over the years, but not death – that is until recently. I’ve worried all my life about what happens after death, (probably nothing, I’ve concluded reluctantly) and I’ve wrestled all my career with the ethics of when life loses meaning and death becomes a preferable option, but I’d never questioned what death actually was. I’d never doubted the parameters I was taught at medical school, or that there was a moment at which we pass from life to death, and I’d never contemplated the possibility of people being brought back from the dead.

Then the husband of a recently deceased patient arrived in our ICU with a “healer”. I’d called him (the husband, not the healer) a couple of hours earlier because the patient was deteriorating fast, and they had set off immediately from the Midlands, but unfortunately arrived an hour after the patient had suffered a cardiac arrest and died. The husband was upset, of course, but he took the news calmly and then looked across to his companion. The healer cleared her throat and looked up at me.

“Thank you, doctor,” she said, “for all you’ve done. We understand what you’ve said, but if it’s OK I’d like to spend some time with her, because I am pretty sure that I can bring her back.”

This was a first for me and, for longer than was polite, I just sat staring at them.

Should I agree? I didn’t want to upset the husband at this difficult time, but what would the other patients and my colleagues think? And what was she planning to do? The patient was in an open ward, would it be noisy? And what if we had missed a weak pulse, she wasn’t dead and they emerged 10 minutes later, triumphant?

In the end I said “yes of course,” mainly because I couldn’t think of a strong counter argument. Then I waited, nervously. Forty-five minutes later, they appeared again from behind the curtains, thanked us once more and left. The healer had apparently been unsuccessful this time, but she seemed unperturbed – you win some, you lose some, I suppose.

For months afterwards I scoffed at the healer’s efforts, arrogant in my superior medical knowledge, but gradually, as I attended more and more ultimately unsuccessful resuscitation attempts, I began to question some of my own assumptions about death.

In 1846, Eugène Bouchut won the Paris Academy of Sciences competition to come up with a way to diagnose death that was both safe and timely. At the time, the public were terrified of being misdiagnosed and buried alive, so many, who could afford it, demanded to be kept in waiting mortuaries until decomposition had begun before being put into the ground – just to be sure. Bouchut suggested listening for a heartbeat with the recently invented stethoscope for five minutes. At that point, he claimed, death could be confirmed, and his definition has stood the test of time. Junior doctors up and down the land dutifully listen for a heartbeat for five minutes (as well as listening for breath sounds, and checking for a response to pain and for pupillary reflexes) and it works. People don’t spontaneously recover after that (a study confirmed that four minutes 20 seconds was the longest time at which spontaneous cardiorespiratory activity resumed after cardiac arrest), but does that mean we’ve worked out when death actually occurs? And what about if we institute cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) at the five-minute point? Death is not declared until CPR has ceased, because CPR is viewed as prolongation of life, not resurrection. If a patient is not for CPR (ie has a DNACPR – do not attempt CPR – order) they can be declared dead after five minutes, but an identical patient next door (who is for CPR) is deemed still alive as they wait, (desperately), for the cardiac arrest team to arrive.

In 2008 the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges stated in its code of practice that:

“Death entails the irreversible loss of those essential characteristics that are necessary to the existence of a living human person, and thus the definition of death should be regarded as the irreversible loss of the capacity for consciousness combined with the irreversible loss of the capacity to breathe. This may be due to a wide range of problems in the body, for example cardiac arrest.”

By this definition, death occurs when we will never be able to be conscious or to breathe again. These two are deemed the essential characteristics of a living person and if they’ve gone, irreversibly, you are dead. We then verify the death by cardiac (as described above), brain (as described below) or somatic (the beginning of decomposition, decapitation etc) criteria.

There is a lot to applaud in the code of practice. It is careful to distinguish between a living person and a living organism, which is vital, as various aspects of the organism continue to live on after death (the nails and hair continue to grow, for example) and the word irreversible is used to rule out situations in which the death-like-state might be reversed (for example in a hypothermic patient or during CPR), but while there is little argument about the somatic criteria, there are still questions around both cardiac and brain death.

The controversy about cardiac death relates to the word irreversible, because we don’t know when the loss of blood circulation becomes irreversible. We decide the point at which it becomes permanent by whether and for how long we attempt CPR. Cardiac death often occurs, therefore, when we decide to stop trying to prolong life, so it is a decision or a judgment, rather than a fact. The patient usually dies when we stop, but if we decide to continue for another cycle of chest compressions, the patient remains alive for that cycle, and occasionally then regains a pulse and lives on. And if we then attach them to an ECMO machine (an artificial external circulation), they could go on indefinitely.

This difficulty with pinpointing the moment of irreversibility means that many people, including me, favour a definition using the word permanent in place of irreversible, but still permanence is at our discretion. The lack of circulation becomes permanent when we judge it to be so and we stop (or don’t start) CPR, so our definition includes what is appropriate for that person as well as what is physiologically possible. Cardiac death is therefore context-specific. As technology and ethics progress, our definition will almost certainly need to evolve, too.

The concept of brain death emerged from our ability to ventilate unconscious patients for prolonged periods. The brain is required to drive our breathing but, supplied with oxygen and nutrients, the heart can go on beating independent of a functioning brain. That meant that the hearts of ventilated ICU patients who had no prospect of consciousness or spontaneous breathing (ie dead patients), could continue to beat for prolonged periods (years even). Not only that, these patients (or bodies) could also absorb nutrients, fight infections and even gestate a healthy foetus to term. Most medics, lawyers and ethicists agreed, however, that if basic brain function had permanently ceased the patient was no longer alive, so criteria were drawn up. In the UK these are called Death by Neurological Criteria and involve two doctors following a strict protocol. They must have an explanation for the brain death, must exclude reversible causes and must then undertake a sequence of clinical tests looking for any evidence of brain stem function, twice. If no function is elicited the patient has legally died (at the time that the first set of tests is completed).

Diagnosing death by neurological criteria is robust, practical, timely and safe, and I support it. It draws a clear line in the sand and allows relatives to begin the mourning process. It also allows heart-beating organ donation (ie the removal of organs from a body whose heart is still beating, for transplantation), which saves and transforms thousands of lives every year. But the criteria are not universal. Different countries have different rules. In the US, Total Brain Failure is required (although often not strictly adhered to), and in other countries further testing is stipulated, such as checking for brain-wave activity or for blood flow to the brain. In some countries, on the other hand, the criteria are less stringent than in the UK; for example, some do not require that the doctors check for a lack of breathing (a crucial part of the UK tests). So it is possible to be declared dead in one country, but then be moved to another where you are alive again. In Japan you have a choice, you can accept the brain death criteria for yourself or reject them (in advance, obviously) and in some states of the US families have challenged the definition on religious grounds, won and then kept their loved one going on a ventilator (at huge expense) for years. It is also possible, with a very specific lesion in the base of the brain, to fulfil the UK criteria and yet still be conscious. In the overwhelming majority of cases this can be excluded categorically, and in the extremely rare cases when it is possible, red flags now exist in the testing guidelines that suggest undertaking additional investigations to rule out any higher brain function.

I am not arguing that we should abandon brain death testing. I think the UK criteria are excellent, but the lack of global consensus highlights that, as with cardiac death, we have made a choice about how to define brain death. We have decided that the loss of certain brain functions equates to the death of a person, but we could have made a different decision. We might have concluded that the essence of life is awareness of our surroundings and that the ability to breathe is immaterial – we can easily support breathing, after all. By those criteria a patient in a persistent vegetative state (or even those with very advanced dementia) might be defined as deceased. We already deem their lives to be of less value than ours by the fact that we limit the medical interventions we offer them, so why describe them as alive at all? Or we could go the other way and be more stringent about our criteria for brain death, and demand ancillary tests such as scans for all patients.

I don’t know the right answer, but I have concluded that though real, death is a process, not a moment around which we have constructed definitions. It is also context-specific, defined both by what is appropriate and what is possible for the individual concerned, so it will change in the future as ethics and technology evolve. Our current definitions of both cardiac and brain death are robust and practical, but we mustn’t regard them as set in stone (as it were). Both religious and secular challenges are likely to become more frequent, and as science evolves and cryogenics or even inorganic living become possibilities, it’s not going to get any easier. Perhaps the first objective should be to agree on a global definition of what we think death is – for now, at least.

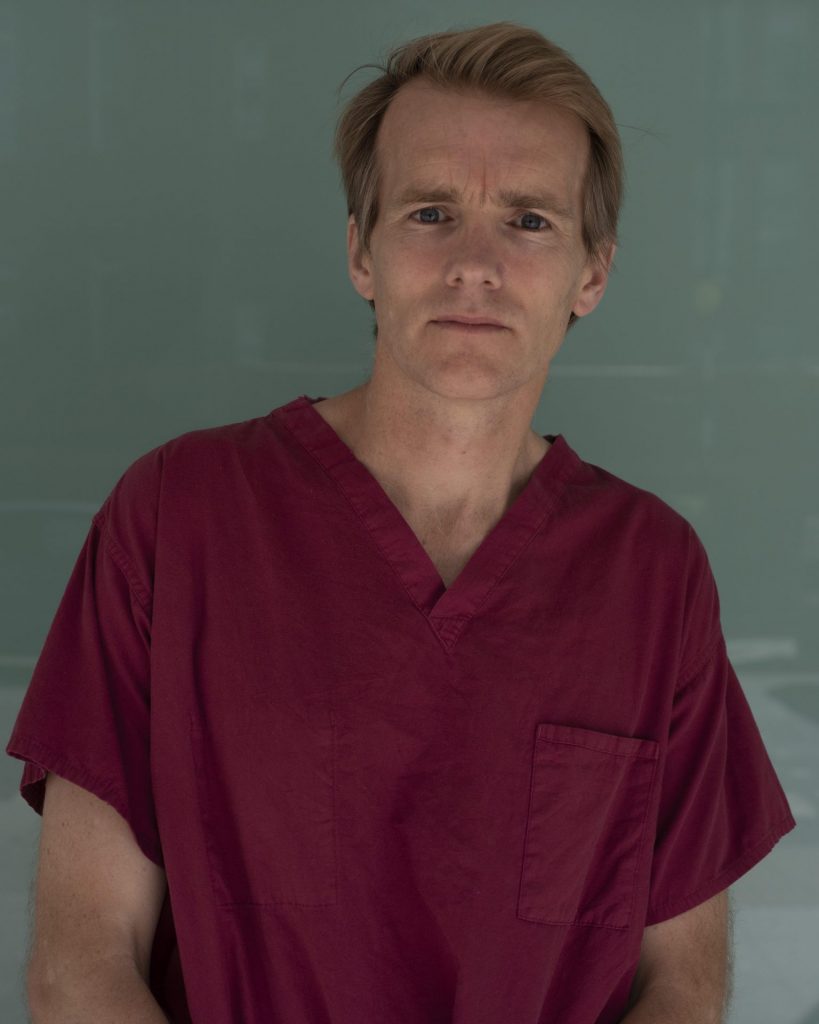

Jim Down is a consultant in critical care and anaesthesia at University College London Hospitals. His book Life In The Balance is out now, published by Viking