‘We had a great adventure in Amsterdam,” says Marc H Miller. In 1979, the American art historian and his then-girlfriend Bettie Ringma, a Dutch photographer, moved into a houseboat moored on the canal at Prinsengracht, two more fledgling beatniks in a beatnik city. Talking to me from his home in Brooklyn, Miller admits that he was perhaps a little “too conservative” for what he encountered.

Over the course of a year, the couple created a bracing, bizarre series of Polaroids taken in the bruine kroegen – the city’s traditional “brown pubs” – as well as its Queer clubs, cabarets, discos and Turkish cafes. Customers commissioned pictures for six guilders a snap as a keepsake from a date or a pub-crawl. Those inebriated instances have now been collected in a book, Selling Polaroids in the Bars of Amsterdam, 1980.

The pictures show establishments steeped in cigarette smoke and alive with volatile and comical encounters. They feature figures with easy smiles and bad teeth, and situations both louche and surreal: a magician with a pigeon playing dead, a woman wearing a live boa constrictor as a turban, drunks squinting into the lens, breasts flashed and trousers dropped. The one constant is the palette of 1980, a muddy bisque of beige and brown.

Miller and Ringma met in Washington in 1974 when she was an aspiring artist and he was a graduate student. Following her divorce from a Dutch diplomat, Ringma bought a houseboat opposite the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam as a way to reconnect with Holland. In one picture, Miller is seen rolling a cigarette on its deck.

“To me, that’s the romance of the bohemian life of the 1970s and 1980s,” Miller says. He explains that he had just finished a PhD in art history when he left for Europe. “But for an American male in the 1970s, a PhD was a form of draft-dodging. It wasn’t so much a career decision; it was a stay-alive position.”

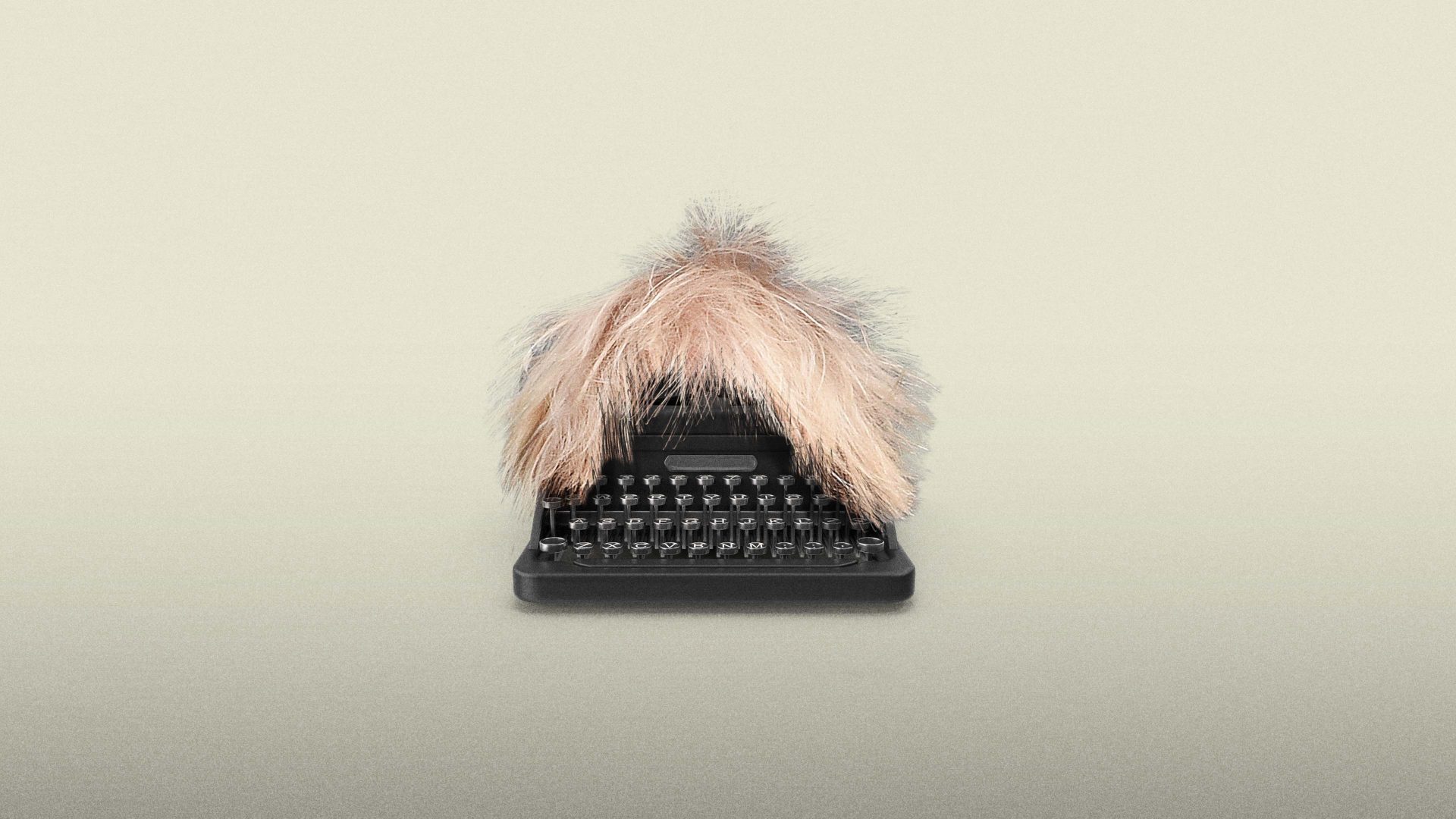

The photographs, taken with Polaroid SX-70 cameras, were initially a way to make ends meet. The pair began not in bars but on beaches, touting around the sands of Zandvoort, 10km from the capital. “We were constantly nervous that sand would get into the camera,” recalls Miller. “There was also the added awkwardness of approaching topless women.” The barflies of Amsterdam were keener on being photographed. As the couple noted, a camera plus alcohol equals money.

Gradually, the enterprise morphed into an art project. “It was the quality of the photos that at first convinced us that we had something worth retaining,” Miller says. In exhibiting their shots in one of the city’s avant-garde galleries they elevated “a vernacular art form that was generally thrown to the wind”. After that, Polaroid provided them with free film to continue their shoots.

The appeal of a Polaroid print is that it is one of a kind, it suits intimacy and immediacy. “There’s often a lot of artful nudes,” Miller says. “It’s also used very heavily when people are setting up shots, especially in fashion photography or movies. Wim Wenders has a collection of Polaroids.”

Miller and Ringma emerged from a New York art scene that had already recognised the medium’s qualities. “Warhol was the one who grasped the ability of Polaroids to be a galvanising force in a social situation, where everybody loves it if they get passed around.”

In Amsterdam, Polaroids chimed with the city’s artistic traditions. With their ashtray pallor and thousand-yard stares, the faces found in the red-light district and other neighbourhoods were worthy of Rembrandt. Likewise, masters of the Dutch Golden Age, such as Adriaen Brouwer, Frans Hals and Jan Steen, were celebrated for their paintings of more-than-merry drinkers.

“Going back to the 17th century, there are all these bar paintings and an interest in tronies, types of people,” Miller says. “In the bars, nobody thought it odd to get a picture of themselves.”

Often, the duo’s subjects appear like dubious characters from novels – a pensive pipe smoker, an elderly lady in a fedora, a weary drag queen, a boxer with a black eye – but there is no judgment here, just undiluted humanity seen in the racket of chatter and the fugue of booze.

Miller and Ringma separated shortly after their Polaroid adventure. He became a curator, while she continued to work on various art projects, splitting her time between New York and Amsterdam. Over the subsequent years, they went through periods of not speaking. “Needless to say, like any relationship there were ups and downs,” says Miller.

Shortly before Ringma’s death in 2018, however, interest in their photographs reignited their friendship. “The more I think about it, the more I realise that all of this stuff exists almost entirely because of her,” Miller says. “She was the one who had the personality to pull it off. She was everybody’s best friend.”

Ringma’s warmth and charisma were pivotal to their success in the unpredictable atmosphere of the bars. “One could see it as potentially dangerous,” Miller notes.

In particular, it could get a “little dicey” when people insisted on a picture with Ringma. One photograph shows her with a man holding a huge flick-knife to her throat: she plays along, a cigarette dangling from her lip in a mock gangster pose, but keeps a tight hold of the man’s knife hand. “Bettie knew how to handle herself and we got away from that one. When you look back – and nothing did happen – it looks one way, and if something had happened it would look another way.”

In the early 1980s, Amsterdam was morphing into a multicultural city. “The more famous photographers in Amsterdam missed that whole side of the changing demographics,” says Miller.

“And we caught it, not because of any great insight into what was going on, we just gravitated to the places that wanted our photographs. The stars were well aligned.”

Selling Polaroids in the Bars of Amsterdam, 1980 is published by Lecturis. Christian House is a freelance writer who contributes to the Financial Times, Sotheby’s magazine and The Art Newspaper