Perton Civic Centre, in a village four miles west of Wolverhampton, is a hive of social activity. You can do Mary’s Keep Fit class on a Monday and play indoor carpet bowls on a Tuesday. It doesn’t exactly look like a place of high political drama.

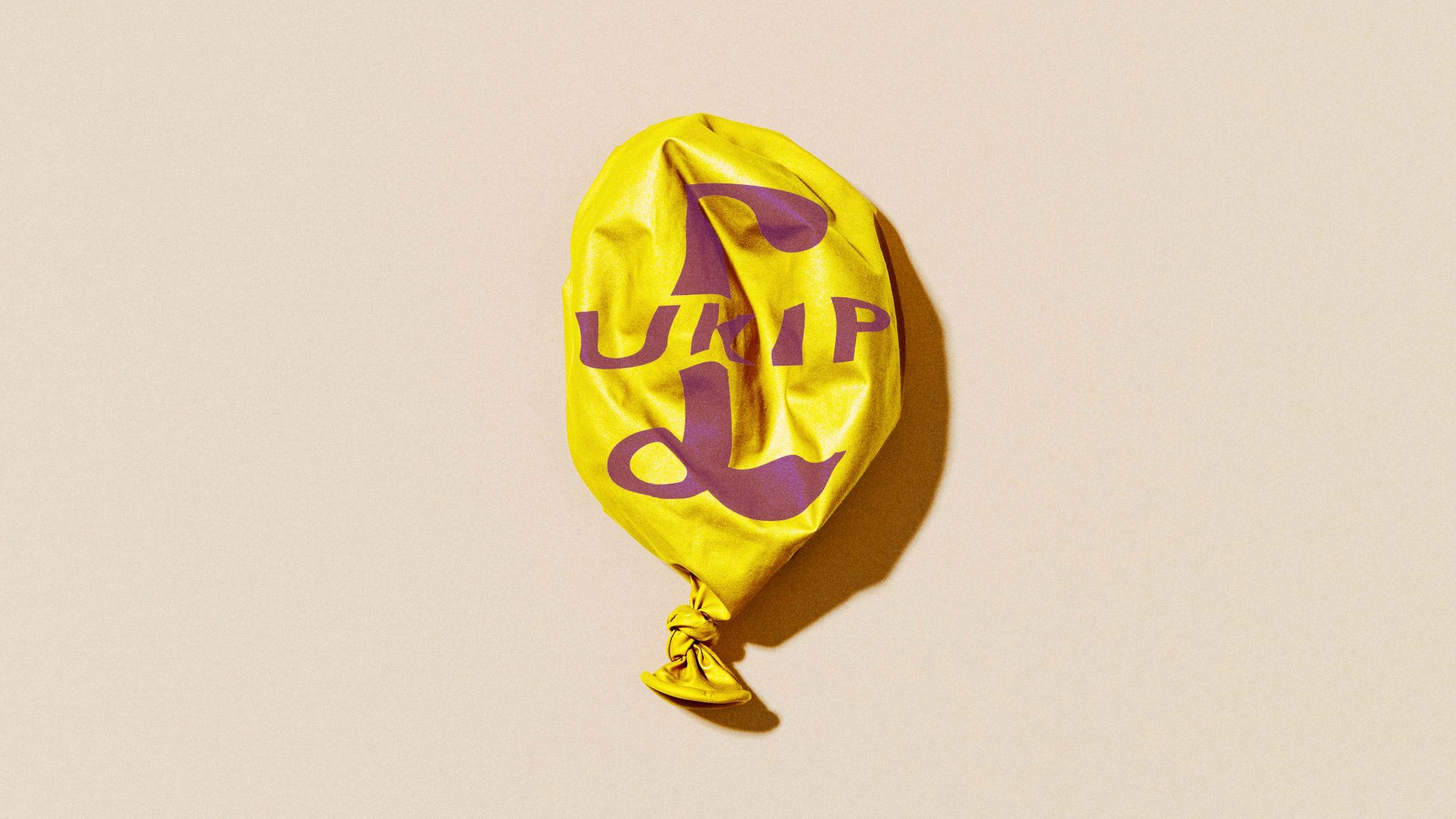

But that’s what it became, sort of, on May 5 this year, as the local election results for the Cheslyn Hay Village ward of South Staffordshire Council were announced. The Conservatives took all three seats in the ward – but, perhaps more importantly the sitting councillor, Steve Hollis, an electrician, lost his. He was among just 50 Ukip candidates nationwide that night. All of them lost – 88% of them came last. Nine years after winning 26.6% of the vote in the 2014 European election and spooking David Cameron into announcing an EU referendum, the UK Independence Party no longer had any elected representatives at any level, anywhere.

There may be some Ukip parish councillors here and there – but they have little responsibility and party affiliation is irrelevant. And that’s it. How did it happen? How did a party once so influential collapse into obscurity in the space of nine years?

The beginning of the fall came in September 2016, when Nigel Farage stood down as leader. Having achieved his life’s goal of wrenching the UK out of the European Union, Farage wanted to see more of his family, make some money and forge a new career in the media. Immediately it became clear that, without Farage, the Ukip edifice looked very flimsy.

Farage’s anointed successor was Diane James, who clearly didn’t want the job. She declined to participate in the official party hustings held around the country. In the job, she gave only one very brief press conference and no interviews before announcing she was stepping down after just 18 days. It later emerged she had written the Latin words vi coactus (“under duress”) next to her signature on Electoral Commission forms confirming her leadership. She quit the party entirely a month later.

James was succeeded by Paul Nuttall, who claimed that he had been present and “lost close personal friends” at the Hillsborough disaster, that he had a PhD and had played football for Tranmere Rovers. None of these things were true. He resigned the day after the 2017 general election, in which Ukip’s share of the vote dropped from 12.6% to 1.8% and the party lost its only MP. The last anyone heard of Nuttall, he was said to be completing his PhD, on the history of the Conservative Party in Liverpool at the turn of the 20th century.

His successor, Henry Bolton managed five months as leader before losing a vote of no confidence at an extraordinary general meeting after a relationship with a model almost 30 years his junior came to light.

Next up was Gerard Batten, an MEP – and it was then that things started to go really downhill. Elected unopposed in April 2018, Batten immediately took the party rightwards, allowing three notorious online figures, Carl Benjamin, Mark Meechan and Paul Joseph Watson, to join the party (Benjamin had infamously tweeted that he “would not even rape” the Labour MP Jess Phillips). It was Batten’s decision to appoint the Islamophobic activist and convicted criminal Tommy Robinson as his adviser on “rape gangs and prison reform”, however, which sealed his, and Ukip’s, demise.

Farage, who had until that point retained his Ukip membership, quit the party, writing that his “heart sinks as I reflect on the idea that they may be seen by some as representative of the cause for which I have campaigned for so much of my adult life”. By the end of the year the majority of Ukip’s MEPs had quit the party. At the start of the following year Farage launched the Brexit Party. Electoral collapse ensued for Ukip. At the European election of May 2019 it won just 3.2% of the vote and the last three of its MEPs who had not defected.

Batten was succeeded by Richard Braine, a software developer whose little more than two months in charge saw him eccentrically refuse to attend his own party’s annual conference. His resignation saw Ukip go into the 2019 general election under the acting leadership of Pat Mountain, best remembered for a car-crash interview with Sky News’ Adam Boulton on the day of the manifesto launch (she could not remember her party’s immigration policy, where it was standing and, responding to questions about whether the party was racist, acknowledged they had no black candidates “but we do have… I think he’s Indian”.) The party won 0.07% of the vote, marginally higher than that of the Ashfield Independents, who fielded one candidate to UKIP’s 44.

Mountain’s successor Freddy Vachha, a koi carp breeder whose CV listed “American” under his languages spoken, took office saying “that shower in Westminster should be quaking in their shoes”. He lasted three months before being succeeded by Ukip’s current, at least nominal, leader, Neil Hamilton.

It is difficult to say with certainty how many members Ukip now has at present, but the party’s 2021 accounts (the most recent available) recorded a membership income of £86,614, which, based on a standard membership fee of £30 a year would equate to 2,887 people (there is a discounted rate for under-25s, but under-25s are not thought to be well represented in the Ukip ranks). To compare that to 2019 – when Ukip were already in serious decline – membership income was £406,753, equating to 13,558 members – a drop of 80% in two years. Other metrics further demonstrate the catastrophic decline in support – donations fell from £711,343 in 2019 to £112,172 in 2021, and total income from £1,162,622 in 2019 to £215,850 in 2021.

Falling numbers have led to the merging of local party branches. For example, Berkshire, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire even relatively recently had their own branches. Now one, the Thames Valley branch, covers them all. Its Facebook page displays an American 1950s-style cartoon image of a girl on a bike and the slogan: “If we White people are so awful, why do you keep moving to our neighborhoods?”

Few members are thought to be active. Ukip’s last national conference was held in October 2022 in the function room of a country pub outside Skegness with the theme “War On Woke”. There were around 50 attendees. In a presentation, which is available on Ukip’s official YouTube channel, Richard Fullerton, chair of the party’s eastern region and billed as a marketing expert, told delegates that “membership is flatlining”.

“Is Ukip still a thing? This is something I get asked when I’m tweeting on Twitter,” he said. “Brexit has made us seem redundant, we’ve become invisible, we’ve lost Farage, we’ve had internal fighting, we’ve haemorrhaged members.”

Hamilton, the disgraced 74-year-old Conservative minister of the 1990s whose life gained an unexpected second act as a novelty celebrity alongside his wife Christine, is officially the party’s leader. His speech to last year’s conference – a rather sad affair, without a raised stage and with the emergency exit behind him – was a ramble, with a lengthy section attacking the epidemiologist Neil Ferguson, and scattered with references to such millennial-pleasing cultural figures as David Niven, Errol Flynn and Ken Dodd.

The far more proactive presence in the leadership is Hamilton’s deputy, Rebecca Jane, a former professional Marilyn Monroe lookalike who has run a detective agency for women suspecting their husbands of cheating and taken part in series 18 of Big Brother, and who now juggles mental health work with GB News appearances (she is also Ukip’s candidate for the Uxbridge and South Ruislip by-election sparked by Boris Johnson’s resignation).

Jane’s focus has been on attempts to unite the parties to the right of the Conservatives, which she refers to as “centre-right” or “splinter parties”. In an email to supporters last July, she wrote: “Let’s start by saying, that to align us all is an incredibly large task and will take a considerable amount of time. However, I am absolutely, increasingly aware that we have deadlines approaching and frankly, if this amalgamation is going to happen, it needs to be soon.

“The process of alignment, and the conversations we have are happening in various ways. What I can conclusively say is that ALL parties who align to our values have agreed to talk, except for Reform.” The Reform Party is led by the businessman Richard Tice.

Ukip’s chairman, Ben Walker, said in March: “We have tried endlessly in the interests of the UK to speak to Mr Tice and have been repeatedly ignored, except for an email from Mr Tice’s journo partner, Isabel Oakeshott, who believed we were all racists for wanting to protect our borders and control immigration.”

Perhaps to aid any amalgamations, in April this year, the party updated its rule book. Previously it had banned any former members of the BNP, National Front, English Defence League and Britain First from joining the party. This exclusion of the far right had been an important tool in Farage’s defence that Ukip had “no truck with extremist organisations”.

Now it proscribes “anyone who is or has previously been a member of Hope not Hate, Antifa, Communist League, Left Unity, Extinction Rebellion, Stop the Oil [sic]”. Walker described this change as “a swing to now exclude the ‘Extreme Left’ as opposed to like-minded, free-thinking people of the right”.

Within days Anne Marie Waters, founder of the far-right group For Britain, rejoined and is now the party’s justice spokeswoman. A day ahead of the announcement Steve Unwin, the party’s spokesman for home affairs, political reform and local government, retweeted a Ukip message saying there was “Big news coming tomorrow” and included the handle of National Housing Party UK. National Housing Party UK is a fringe organisation that shares extreme right-wing material on social media.

At Ukip’s spring conference in Winchester this year, during a Q&A with Jane, one delegate rose to speak. “It’s not a question, it’s just a statement,” she said. “I think I have an idea how we can stop these boats. Just simply announce that everyone crossing illegally will be shot. Actually shoot the bastards, that’s how.” The reaction was a mixture of applause and laughter. Jane responded: “For the sake of this being recorded, no comment.” That video is also publicly available on Ukip’s official channel.

“My ambition whilst I’m leader of Ukip is to put us back up there in the frame where we are the dustbin for people’s discontents and we are an effective party of protest because, by God, there’s plenty to protest about,” Hamilton told his party’s annual conference last year

“Let’s all ensure that Ukip does survive, does prosper and we can continue to provide the real opposition which no other party’s providing.”

But it is not surviving, or prospering. Instead, it is a party with no elected representatives, giggling about shooting desperate migrants in a hotel function room.

RIP Ukip. Died Perton Civic Centre, May 5, 2023.