Shasta is sold into slavery. They’re dickering over the price when he slips out, to where the horse belonging to the purchaser is tethered. He wonders what his new master will be like. Surely the horse would know. “I wish you could talk, old fellow.”

“And then for a moment he thought he was dreaming, for quite distinctively, though in a low voice, the Horse said, ‘But I can.’”

This is from the first chapter of The Horse and His Boy, a volume in the seven-part Chronicles of Narnia by CS Lewis. It was first published in 1954, but talking horses in literature predate this by getting on for 3,000 years.

In the blood-spattered power struggles of The Iliad, Achilles has two immortal horses, Xanthos and Balius. After the death of Achilles’s best friend Patroclus, Xanthos is given the gifts of speech by the goddess Hera, He addresses Achilles – but his words are not the delicious surprise experienced by Shasta and the readers of The Horse and his Boy.

“We shall surely save you for now, mighty Achilles.

But your day of destruction is near…”

It won’t be the fault of the horses either: a god will be responsible. The prophetic horse is then silenced by the Furies, and Achilles says that Xanthos had no great need to speak. He knows he’s going to die in this war – but not before the Trojans have paid a price.

The introduction of talking animals makes an instant statement: this story has a fantastical agenda. The horse’s first speech in the Narnia story sets the tone at once for newcomers and confirms it for those who have read the other books. Animals talk: don’t expect uncompromising realism.

Xanthos doesn’t speak until Book 19 of 24, by which time we’re well accustomed to the capricious interventions of gods into human lives. The speech of Xanthos is no great stretch: and it prepares us for the terrible events that bring about the death of the hero, but not before other horrors have been played out first.

Animal speech changes everything. It would be a different book if Moby Dick spoke in good English to Captain Ahab, or if the cat in Ulysses had said “thanks for the milk, Poldy” rather than “Mkgnao!” But a talking animal doesn’t trivialise the narrative; only authors – and readers – can do that. When animals talk they tell us to forget naturalism. Talking animals can be delightful, they can be sinister, they can be nauseatingly cute and they can be truly horrifying.

They crop up in a million stories for children, like those written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter. They can also be found in stories of maturity, in books no child could easily grasp. There are also many stories that exist in the half-world that lies between childhood and adulthood.

Such books operate in a liminal state in which children anticipate adulthood by reading a little beyond their years and in the same pages, adults willingly return to certain aspects of childhood, in a way that enriches rather than demeans. The Narnia books become for some an adult pleasure, for the books’ subtle readiness to lift the spirits by taking on big themes.

Talking animals can also be dreadful. Take the morning on which Gregor Samsa wakes “from uneasy dreams” to find himself “transformed into a gigantic insect”. He answers the calls of his family through the door in what was “unmistakably his own voice, it was true, but with a persistent horrible twittering squeak behind it”.

This of course is the beginning of The Metamorphosis, a novella by Franz Kafka. It tells of Gregor’s life as an insect, the kindness of his sister Grete, the violence of his father, the pain of his existence and his eventual death from despair.

There are many interpretations of this parable, if it is a parable, and the reader can pick one or all or none. What comes through without ambiguity is the horror of feeling cut off from the rest of humanity – and that’s something experienced by everyone who has ever existed.

Kafka’s work is full of creatures who are half-human yet not at all human: half-and-halfers, neither one thing nor the other. In A Report to an Academy, the academy is addressed by an ape who has, by an effort of will, made himself human: “No, freedom was not what I wanted. Only a way out…”

There is also an essay by a philosophical dog and an account of a pack of talking jackals who treat the narrator as their messiah. All these highly articulate animals make the big topics they discuss both comic and sinister, packed with meaning and at the same time absurd.

Behemoth comes into the sinister-yet-absurd category. He is a monstrous cat – “big as a hog” – who is part of the devil’s retinue when he pays a visit to Moscow during the atheist and Stalinist years, in The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov.

Behemoth is the greatest invention of a wildly inventive novel. In an early chapter he gets on a tram: “Both conductress and passengers seemed completely oblivious of the most extraordinary thing of all: not that a cat had boarded a tramcar – that was after all possible – but the fact that the animal was offering to pay its fare!”

Behemoth has a taste for chess, vodka and the occasional gunfight; he takes a special delight in arson. When he speaks – he’s rather a laconic cat – he is given to vicious sarcasm: “I protest… Dostoyevsky is immortal!” he says as he blags his way into the writers’ club.

Once again we seem to be in an allegory of some kind, but it’s never quite clear what’s being allegorised. Rather we must deal with chaos and anarchy, with irresponsible love of power, and how the world works when it lacks belief in just about anything.

Allegory and fable are there in the front seat as soon as an animal opens his mouth or beak. We are taken back to the improving tales of Aesop, and of the homely truths recounted by his foxes and crows and lions, who all date back to a time not much later than that of The Iliad.

These tales are so much a part of western culture – and other cultures too – that we accept them almost subliminally. Every time an animal speaks, we are waiting for him to dramatise some essential truth about human life. The trick, then, is to make the tradition work for you, either by subverting it, as Bulgakov and Kafka do in their different ways, or by going along with it.

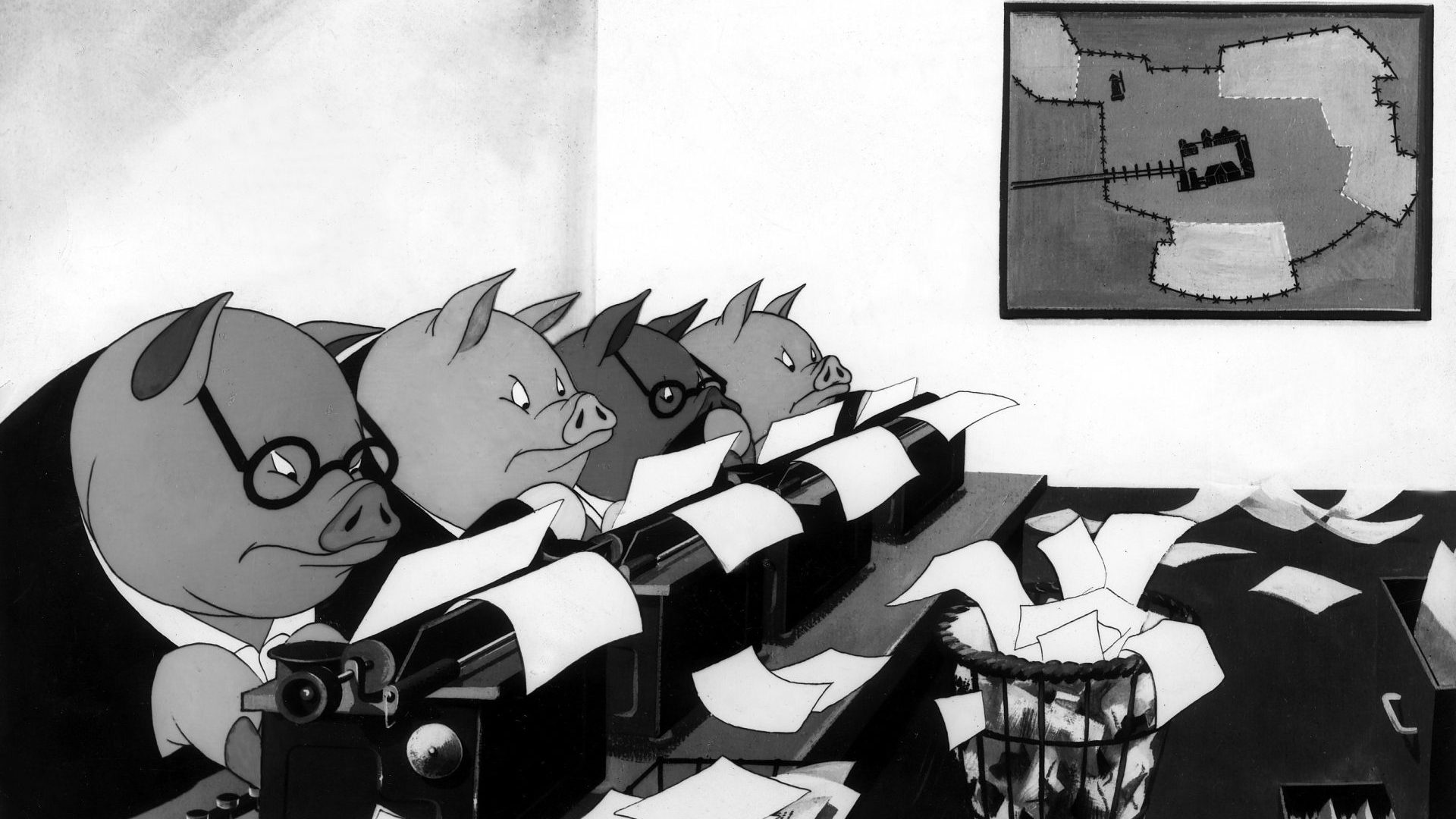

George Orwell’s Animal Farm is another of those liminal novels, reaching out to the child that exists in adults and to the adult in the growing child. I remember my delight in the first chapter; I suppose I was 13 or 14. I was utterly taken up by the joy of the revolution and was convinced that from now on everything would be good. The perfect society was being created before my reading eyes.

The animals throw out Mr Jones the farmer, take over the farm and manage the place for themselves, far better than Jones ever did, under the slogan “all animals are equal”. The story reflects the history of the revolution in Russia; naturally, the pigs are in charge, being the most intelligent animals, but they operate benignly and all is wonderful. At first.

Then Napoleon seizes sole control. The noble worker, the horse Boxer gives his all: “Napoleon is always right. I will work harder.” He grows too old to work and his reward for loyalty is to be sold to the knacker-man. It’s a heart-breaking betrayal, does every first time reader weep?

The key slogan is amended: “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others”. The book moves on to its inevitable end: the pigs are in charge and Napoleon is supreme. They make accord with the world of men, and then comes one of the most famous pay-off lines in all literature: “The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again, but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

Perhaps the most famous talking animal of them all can be found in the third chapter of the first book of the Bible, when the serpent, inhabited by the devil and more subtle than any beast in the field, tells Eve that if she and Adam eat the forbidden fruit “ye shall be as gods”.

Pick up any newspaper today and almost every story will, at its heart, be about someone seeking to be as a god. This theme – power for the simple love of power – was picked up by John Milton in Paradise Lost, as he retells the tale of Adam and Eve, and how the serpent “the fittest imp of fraud” addresses Eve, telling her that she is so beautiful that she should be seen as:

“A Goddess among Gods, adored and served

By Angels numberless…”

She agrees, and all is lost.

HH Munro, who wrote under the pen-name of Saki, loved to puncture Edwardian Edens and to toy with their traditional hypocrisies. He also delighted in introducing feral creatures into drawing rooms, especially at tea-time.

A guest at a house party teaches his hosts’ cat to speak. Tobermory is a cat through and through, first telling his impatient owner that he’d join them at the tea-table “when he dashed well pleased”. He is then asked his view of human intelligence, “mine for instance”: “’You put me in an embarrassing position’, said Tobermory, whose tone and attitude certainly did not suggest a shred of embarrassment.”

He tells the assembled guests what they all really think of each other, and when someone attempts to get the better of him says: “From a slight observation of your ways since you’ve been in the house I should imagine you’d find it inconvenient if I were to shift the conversation to your own little affairs.”

The assembled company plot to poison Tobermory: society can’t operate in the face of a truth-telling cat, after all. The story – titled Tobermory – is a six-page tour d force, one that certainly sets the cat among the teacups of polite society.

Mowgli, the feral boy in Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book and its sequel, is initiated into the polite society of the wolf-pack and grows to understand the beauty of the Law of the Jungle. He learns all the animal languages and they speak back to him in rolling phrases that echo the King James Bible.

But the wolves eventually turn against Mowgli because he is a Man. Cast out, he asks his friend and protector Bagheera, the black panther if he is dying. “No, Little brother. Those are only tears such as men use.” They are powerful tales, packed with meaning. The animals speak and the human in the jungle is enriched and ennobled by what he learns from them.

Polynesia the parrot teaches Dr Dolittle animal language. The Cheshire Cat grins enigmatically from the sky in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Winnie-the Pooh is an idiot savant; Ratty and Mole live on the river-bank in The Wind in the Willows; Paddington comes to England from Darkest Peru and is welcomed by the Brown family; Hazel and the other rabbits re-enact The Odyssey in Watership Down; Harry Potter is fluent in snake language or Parseltongue.

Talking animals have enriched our literature and our lives. But I’ll leave the last word to the cow that appears in Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker series. At the Restaurant at the End of the Universe Arthur Dent is offered a cut of beef – by the cow itself. “Good evening… I am the main dish of the day. May I interest you in parts of my body?”

As a comment on the relationship between human and non-human animals, it is perhaps unimprovable.