When it comes to literature that is challenging, experimental or even just playing around with traditional forms and structures, there is always a danger of it being hamstrung by a certain earnestness.

Some authors who push against, or even through, established boundaries produce exhilarating results, revealing a freshness of thought and technique that can revitalise a tired genre. Too often, however, the results turn out to be a sally into self-indulgence, a writer setting out to prove a point and bolting a narrative to it in a way that proves deeply unsatisfying as a reading experience.

The reader is, of course, the important one here. Books are written for readers after all, which is why when one picks up a book that appears to have been created for reasons other than providing the reader with an enervating and even entertaining experience, we feel short-changed.

Writers should of course be readers too; the journey to authorship begins with absorption in other people’s books, experiencing the magic of entering a world of characters separate from the one we inhabit and being inspired to emulate them. Writing comes from reading, and the best writing comes from authors with a deep love of reading.

I’ve read too many authors who never give the impression they actually love reading, authors who have appointed themselves to change the face of literature apparently without experiencing enough of it themselves. Maybe they feel they don’t have to, convinced enough of their own genius and destiny to have largely dispensed with other writers’ work. For them the reader is beneath them, meaning their books are frequently turgid, overwrought and utterly joyless.

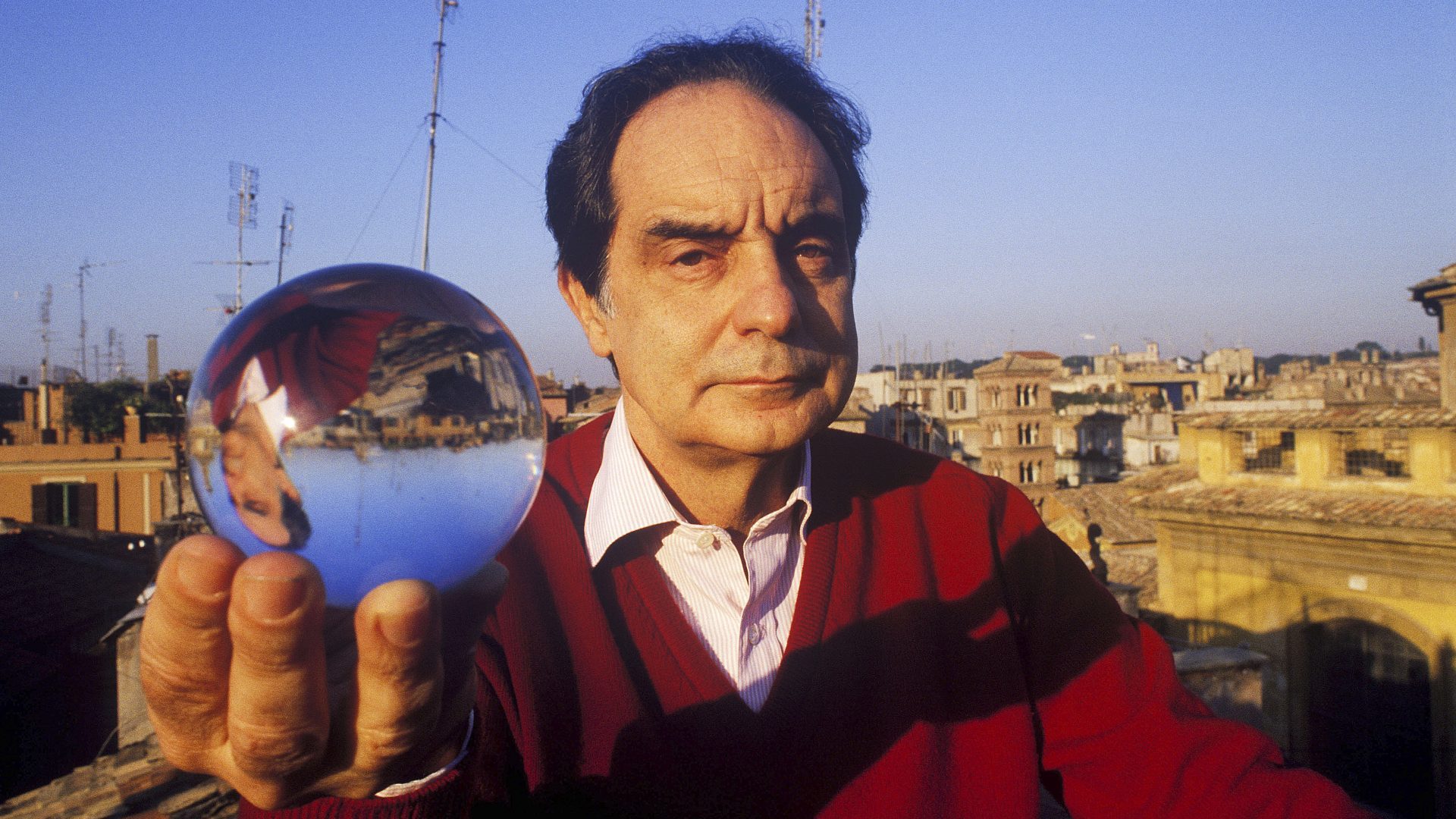

There is nothing more refreshing than finding that a writer who has genuinely changed the face of modern literature is also an avid reader, someone who shares the thrill and excitement of reading as a source of fulfilment with the people who buy their books. No writer exemplifies this better than Italo Calvino.

The Italian writer, who was born 100 years ago this month, was a literary all-rounder of extraordinary prolificity. He was only 61 when he died as the result of a stroke, but left behind enough fiction, non-fiction, journalism and letters to fill a life twice as long. Salman Rushdie had it about right when he wrote in 1981: “One of the difficulties with writing about Italo Calvino is that he has already said about himself just about everything there is to be said”.

Calvino is best known for novels like Invisible Cities and If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller, but last week when I felt I should mark his centenary, it wasn’t to one of those old favourites that I turned. Instead I reached for The Written World and the Unwritten World, a volume of his collected non-fiction issued earlier this year in Ann Goldstein’s translation by Penguin Modern Classics.

A gallimaufry of Calvino’s journalism, essays, interviews and introductions to books issued as part of his job as an editor at the Italian publishing house Einaudi, the book is a testament to how Calvino, for all his justifiably elevated literary status, was at heart one of us. He loved reading and remained in awe of writers and writing throughout his life, which helped to make his books as accessible as they were innovative.

“I belong to that portion of humanity – a minority on the planetary scale but a majority I think among my public – that spends a large part of its waking hours in a special world, a world made up of horizontal lines where the words follow one another one at a time, where every sentence and every paragraph occupies its set place: a world that can be very rich, maybe even richer than the non-written one, but that requires me to make a special adjustment to situate myself in it,” he writes as the opening to the essay that gives the book its title.

Reading Calvino never feels like he regarded any aspect of his writing and reading lives as a chore. His prose grabs you by the lapels and his enthusiasm and endless curiosity fizz from the page, all fired by a profound love of books.

In his 1984 essay A Book, Books, written a year before his death, he accepts that the nature of books would change in an era of computerised technology. Noting the rise of the word processor, he predicts that libraries will become repositories of microfilm rather than paper, lamenting that “I am fond of books also as objects, in the form they have now, even if it’s increasingly rare to see editions that express love for the book-as-object, which as a companion for our life should be beautifully made”.

Nowhere is his enthusiasm more profoundly presented than in his 1959 Answers to Nine Questions on the Novel for the magazine Nuovi Argumenti. Asked to select his favourite writers and explain why he admires them, Calvino unleashes a passionate torrent of literary admiration.

“I love Stendhal above all because only in him are individual moral tension, historical tension, life force a single thing, a linear novelistic tension. I love Pushkin because he is clarity, irony, and seriousness. I love Hemingway because he is matter-of-fact, understated, will to happiness, sadness. I love Stevenson because he seems to fly. I love Chekhov because he doesn’t go farther than where he’s going. I love Conrad because he navigates the abyss and doesn’t sink into it…”

And so on, taking up a full page of The Written World… as if he had waited years to be asked this question with names like Tolstoy, Manzoni, Chesterton, Twain, Kipling and Mansfield, each with a justification for his enthusiasm even if his love for Jane Austen is “because I never read her but I am glad she exists”.

When it came to his writing, when asked by the French newspaper Libération why he wrote, he admitted to a mixture of self-doubt and inspiration familiar to us mortals.

“I write because I’m dissatisfied with what I have already written and would like in some ways to correct it, complete it, offer an alternative,” he says. “I have the thought: ‘Ah! How I’d like to write like X! Too bad it’s completely beyond my capabilities!’ Then I try to imagine this impossible undertaking, I think of the book I will never write but would like to read, to put beside other beloved books on an ideal shelf. And suddenly some words, sentences appear in my mind…”

This technique was most tangibly and most successfully implemented in Calvino’s 1979 novel If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller, arguably his masterpiece and the work in which his love of literature is most overtly expressed as he seeks to recreate the world of reading on the page.

“You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller,” it begins. “Relax. Concentrate. Dispel every other thought. Let the world around you fade.”

You, the reader, are transported to a bookshop to select and buy If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller but find after reading the opening pages there has been a printing error and the same pages are repeated. You return it to the shop, select another book and the same thing happens, again and again, until the reader has read the openings to ten different novels by different authors.

“My principal idea was to write a book in which the reader would not be reading the text of a novel but a description of the act of reading per se,” he said of a work that was innovative and experimental yet still left the reader satisfied and feeling they had been invested in the concept from the start.

Above all, Calvino’s work was joyful. As Rushdie said in his 1981 essay, “Reading Calvino, you’re constantly assailed by the notion that he is writing down what you have always known, except that you’ve never thought of it before. This is highly unnerving: fortunately, you’re usually too busy laughing to go mad”.

The Written World and the Unwritten World covers a range of subjects, from the act of sitting to the grail knights, from procrastination to an imagined encounter over a board game between Montezuma and Cortès, but even the most recondite chapters brim with passion, incisive intelligence and wit that still treats the reader as an equal, especially when discussing a shared love of reading.

The opening essay analyses the rewards and agonies of selecting books to take on holiday, followed by what he calls the Good Reader’s return to “the rapid concentrated quarters of an hour granted to reading before he goes to sleep, before rushing to the office, in the tram, in the dentist’s waiting room”.

Calvino was a writer who understood readers because he was one. Few writers, certainly not writers as stylistically adventurous as he was, had such a deep understanding of the world of the reader as Calvino because he happily inhabited that same world. He knew what it meant to be a reader and recognised the privilege granted to an author that someone might spend some of those invaluable snatched quarter-hours with their work to escape the everyday. He knew that privilege had to be earned, even as he subverted the entire established form of the modern novel.

As he said in Why Do You Write?, “I consider that entertaining readers, or at least not boring them, is my first and binding social duty”.

The Written World and the Unwritten World: Collected Non-Fiction by Italo Calvino, translated by Ann Goldstein, is published by Penguin Modern Classics, price £10.99