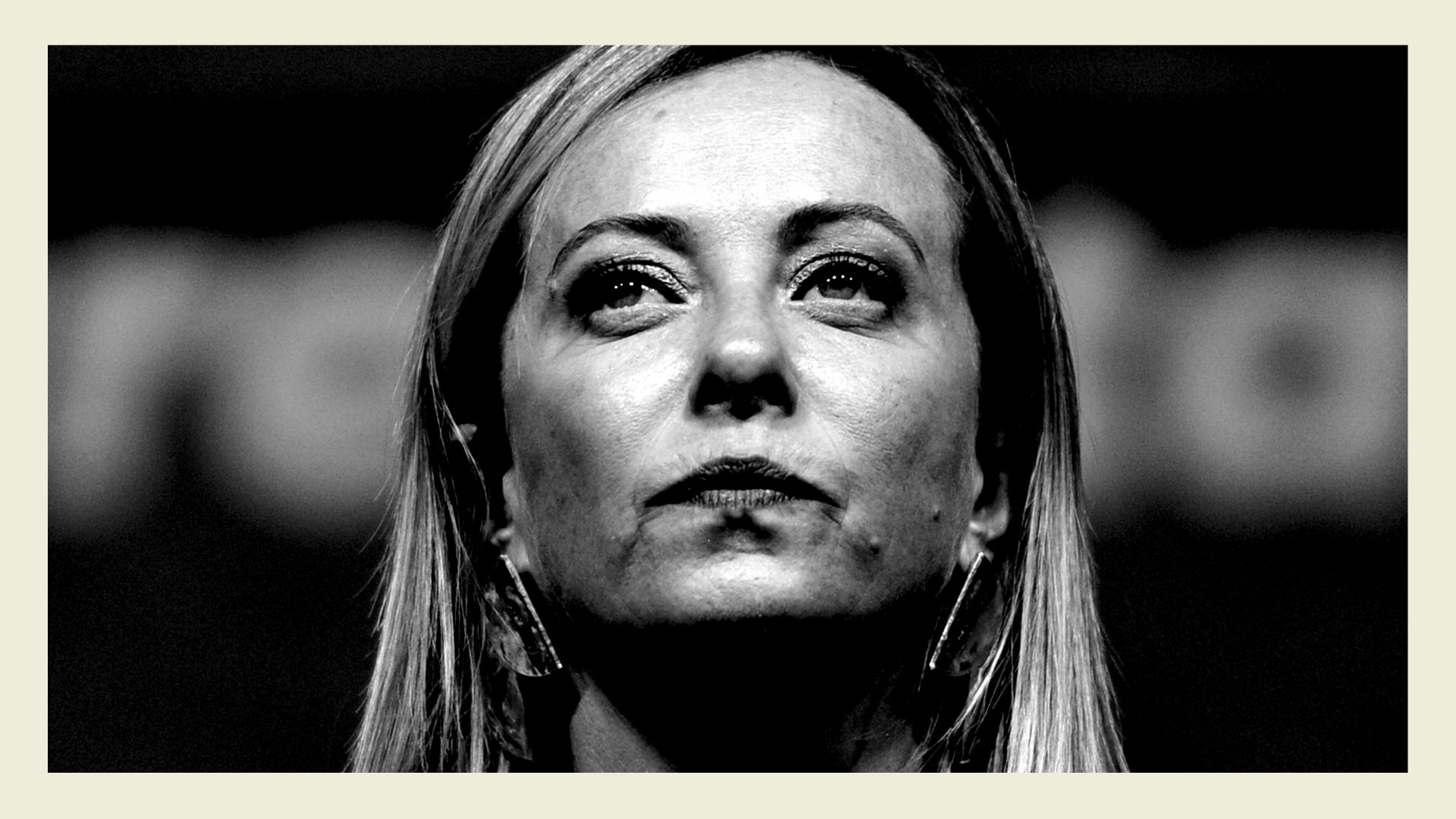

At first glance, Italy looks like a feminist success story. The country boasts its first female leader, the right winger Giorgia Meloni, and more women are forging successful careers, especially in law. According to figures from the Cassa Forennse, the Italian state social protection body for law professionals, Italy had 117,559 female lawyers admitted to the Bar Association in 2020, the highest total number of any European country. In comparison, the UK and Wales recorded the next highest number with 77,531.

Italy has a long history of women in the legal profession. The first woman to earn a law degree in Italy was Lidia Poët, and she achieved that goal – remarkably – in 1881, just seven years after women were first accepted into Italian universities.

It would seem then, that Italian women are making progress. But in reality, a concerning amount of women are trapped in the lower echelons of the professions, while their male colleagues ascend the ranks around them. The reality is that, despite its new female leader, Italy remains a feminist blackspot.

Poët earned her law degree from the University of Turin, and she wrote her thesis on women’s status in society and their right to the franchise. Two years later, she passed the equivalent of the Bar examination and was admitted to the Order of Lawyers and Prosecutors of Turin by 45 votes to 50, making her Italy’s first female lawyer. But her moment of triumph was short-lived.

The attorney general did not approve of Poët’s success. In a struggle portrayed by Matilda De Angelis in the new Netflix series, The Law According to Lidia Poët, he lodged a complaint with Turin’s Court of Appeals which was upheld, meaning that, three months after qualifying, she was struck off. She was eventually reinstated in 1920. But in that time, while not technically permitted to practice law, Poët continued her legal work in her brother, Enrico’s, office. When he travelled to Vichy each year, she took overall control of the firm, while remaining invisible.

According to a study completed in 2017 by the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs, women are constantly pushed into these “invisible background roles” within law firms across Europe. On top of this, women also represent the “working class” level of the legal services market. As a result, their opportunities for promotion can be limited to the lower echelons of the professional hierarchy.

Italy follows this unwelcome pattern. Barbara de Muro, a leading corporate lawyer and partner at the law firm LCA tells me that, according to the EU Justice Scoreboard 2022, it has the highest number of lawyers in Europe, with approximately half of them women. “When analysing data on partners or senior roles in law firms, however, there are far fewer women than men,” she says.

De Muro is also head of the Italian Association of Law Partnerships Women (ASLA Women), a working group that aims to improve the prospects of women in the Italian legal profession. In 2018, the group found that a mere 20% of equity partners are women. When it comes to partners who bear no risk, and who take a salary, the number is 24%.

According to the Cassa Forense, in 2018 female lawyers earned less than half that of their male counterparts. It is a divide that occurs across the country, despite age, although it is more prominent in the older generations and, interestingly, is not affected by a woman’s decision to have children. It’s a gap that time has failed to bridge. Data from a 2022 report by the Italian Center for Social and Economic Research shows a significant income gap. “Even today the difference in average income between a man and a woman is so stark that you must add the income of two women to match the income of a male colleague,” Francesca Bodo Corona, leading criminal lawyer and founding partner of the Avvocati 10100 Torino law firm.

Moreover, the 2017 study from the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs found that women often opt for areas of law that are less profitable, but more stable. Family law, for instance, can fit tightly into a schedule, in most cases, and is unlikely to cause weekend work.

Wilma Viscardini doesn’t want to be called a feminist. Nor does she want to be called avvocata, “a female lawyer”. The senior partner and founder of the Donà Viscardini law firm prefers avvocato – with the male ending.

Though avvocata is grammatically correct, many women, including Viscardini, object to using it, claiming it is not taken as seriously as the masculine version. For Viscardini, avvocata emphasises her gender more than the fact that she is an attorney. Avvocato, meanwhile, simply designates her profession, regardless of sex.

De Muro’s preference, however, is different. She prefers avvocata, explaining that not only is highlighting her gender significant, but essential in recognising the existence of women working in the profession.

Today, it remains a highly politicised debate. “Every day, somebody asks me which I prefer to be called,” Bodo Corona explains. Except, these enquiries often are not limited to avvocato and avvocata. At points in her career, Bodo Corona has been called doctoressa, the Italian term referring to a university graduate. People assumed she was a trainee.

Like Poët, Bodo Corona enrolled at the University of Turin’s law school with two very clear ideas. One – she would become the first lawyer in her family; and two – she would specialise in criminal law. “That was my ambition,” she tells me, “and so I did.” In 2009, she obtained her master’s degree in law, dropping just two marks in her thesis on the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the massacres in Guatemala. Nearly 150 years after Poët, Bodo Corona was subsequently enrolled on the province’s Bar Association in 2013 as a criminal barrister. Also, like Poët, however, she soon realised how rife sexism and misogyny were in the legal world.

On more than one occasion, Bodo Corona found clients were deterred by her gender, rather than impressed by her years of legal experience. Once, after escorting a potential client to the conference room, he turned, thanked her and asked: “Doctor, when does the lawyer arrive?”

Another time, a male client decided only to engage her services upon learning from the law firm’s website that she would have male colleagues to guide her decision-making. “Since then,” she admits, “I and one other female colleague have gone on to win three cases for him.” When she first began her time as a lawyer, de Muro faced the same objection from a male client, who wanted to work with men only. The male partners at the firm, however, suggested the client reexamine his thinking, leaving him no choice but to engage her services. “Today, 20 years later, I am still working for the client who, for the sake of clarity, changed his mind immediately about women lawyers,” she says.

This hasn’t always been the case for Bodo Corona. “Several years ago, while I was chatting with a peer in the courthouse’s hallway, we noticed a pregnant colleague entering the courtroom a bit out of breath. ‘When a woman decides to give birth to children, she must understand that she cannot be a lawyer,’ he said to me. Perhaps he forgot I had two small children,” she says. Opting for a stony silence, she turned and walked away.

“Colleagues still maintain today that the legal profession is not a woman’s affair and that, therefore, my energies expended in this field are inappropriate. An older colleague told me exactly that seven years ago,” Bodo Corona says.

Decades earlier, Viscardini endured similar remarks. She was the city of Rovigo’s first female lawyer. After graduating in 1956, she began her legal training at a small firm in her hometown before going on to later pass the Bar exam. “To tell you the truth, my success was due to the novelty of being a woman,” she says. She may well have remained a provincial lawyer, had her fiancé (and later husband), Gaetano Donà, not drawn her attention to the new field of law at the European level. When the European Commission was founded in 1958, as she spoke French, she was able to apply for a legal advisor role.

“Even at the European Union institutions,” she explains, “there was some resistance and scepticism to accepting women into roles that had historically been held by men only. So initially, I had to make do with a position in the Department of Statistics.” Thanks to her perseverance, she was later accepted into the Legal Service of the Commission as a lawyer and she vividly remembers her welcome by the Director General: “You are the first woman, it will depend on you whether there will be a second”.

She would go on to be the first female attorney to present a defence of the Commission before the Court of Justice and spent the remainder of her time there working for the Commission in Brussels as the European Economic Community (now European Union) was developed. However, when she returned to Italy in 1974, much to her frustration it appeared her years in Brussels and Luxembourg were lightyears away from national realities, especially in Italy. And so, Viscardini got to work on the case of Donà v Mantero.

“Hardly anyone had realised that there was now a new system,” she explains. In particular, there were no EU law courses in Italy so judges and lawyers were unaware that they could draw upon this in their judgements. The case of Donà v Mantero changed this. To put it another way, one woman transformed how European law was used in Italy.

In the 1970s, Italian football clubs did not perform well in European competitions, winning only two of the 29 major European trophies on offer during the decade. No Italian team won the European Cup (now known as the Champions League). “The managers of the major teams attributed this lack of success to the autocratic policies which dictated that only Italian citizens could play in Italian teams,” says Viscardini. Soon, she was approached by a major club manager inquiring about the possibility of hiring foreign footballers, to which she answered that, if they were hiring from another member state, the principle of free movement of workers should permit this. Failing to convince the manager to take legal action, she resorted to doing so herself and the case of Donà v Mantero began; Dona being her husband, a football fan and convinced European, Mantero, the manager of the Rovigo football club that played in a minor league.

“Donà first looked for a Belgian player willing to transfer to Rovigo’s team,” she tells me. They then placed a successful advertisement in a Belgian newspaper looking for foreign players. “Mantero refused to hire the player or reimburse the expenses on the pretext that he did not believe this was legally possible. Donà, represented by myself, sued Mantero before the competent national court,” continues Viscardini.

The court asked the European Court if European law should be interpreted to mean that professional footballers were permitted to work anywhere within the community and they responded that it should. Viscardini had won her case.

“The “Donà/Mantero” ruling of 1976 thus opened the borders to European Community football players,” says Viscardini.

Carmela Devita, a third-year law student at the University of Turin specialising in EU and international law, can’t see how Poët is remembered at her university at all. “Since I started my bachelor’s degree, I have not heard anyone mention her name or discuss her achievements. At least, not before the recent announcement of the Netflix series about her life.” Moreover, her legal heroes stretch far beyond Italy’s borders, citing names such as former supreme court judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg and congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

And yet, as reported by the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs, men still made up 60% of Italian public prosecutors (in first instance courts), which is perhaps a cultural problem – the division of male and female roles in the family realm disrupts workplace promotion. But for Bodo Corona, the debate over the place of Italian women in the law – and in the workplace in general – should be concerned with “professional expertise” and “self-awareness” rather than simply gender inequality. “After all,” she says, “in the courtroom, all criminal lawyers wear a gown. That is the same for all. That cancels out all our differences and stereotypes.”