“The meaning of my life is football, and that is frightening,” says Arsene Wenger at the start of a surprisingly emotional new documentary about his extraordinary achievements in football management. “Perhaps I have loved it too much.”

The film, Arsene Wenger: Invincible, is about balls, but the human kind more than the ones hitting back of a thousand nets. It’s about obsession, perfection, driving ambition and bitter defeat. At its best, it achieves a spiritual, meditative quality amid drama and heartbreak.

It is co-directed by Gabriel Clarke and Christian Jeanpierre. Clarke is well-known in the UK as ITV Sport’s touchline reporter, delivering the preview features and post-match interviews at England games and throughout the first, formative 25 years of the Champions’ League. Jeanpierre is known in France as “Monsieur Foot”, the face of the legendary weekly TF1 show Telefoot and commentator, with punditry supplied by Arsene Wenger, on hundreds of games for the national team, following Les Bleus to Euros and World Cups.

As we wait to go on stage together at the film’s premiere in Finsbury Park, just the length of a few football pitches away from Highbury, scene of Wenger’s greatest triumphs, Jeanpierre, Clarke and I discuss the film and the legend we are about to interview in front of a very starry crowd of former and current Arsenal luminaries.

“When you commentate with Arsene, you learn about football,” Jeanpierre tells me . “You see a new aspect of the game every match, or spot something new in the character of a player. But making this film with Arsene, I learned about life.”

Only a few days previously, Clarke was covering a chilly 1st round FA Cup tie between Sheffield Wednesday and Plymouth Argyle. It finished 0-0. In the morning, he’s off to grab a few minutes with England’s Declan Rice for a pre-match package. But alongside this obsessive commitment to reporting, Clarke has developed an impressive career as a documentary film maker of considerable quality. I knew him a bit back when I was a football reporter myself (Daily Express, 1994-1996, more of which later) but re-connected when he was at the Cannes Film Festival in 2015 with his fine debut cinema doc Steve McQueen – The Man & Le Mans. Since then he’s made award-winning films about former Barcelona, Newcastle and England boss Bobby Robson and, most recently, the England World Cup winner and Republic of Ireland manager in the incredibly moving Finding Jack Charlton.

Clarke is pacing like an expectant father, anxious that Wenger, who’s inside the cinema watching the finished film for the first time, is satisfied with the outcome. “It has been the work of many years to get him to make this film,” he says. “I’ve asked Arsene countless times and I know he’s had the offer many times, for many millions of dollars from other sources, and it took the persuasion and involvement of Christian to get it over the line.”

In fact, the film-makers made two films at once, one in French, the other in English, with Wenger basically recording his interview answers first in French and then in English. “He says practically the same thing in both,” Christian assures me.

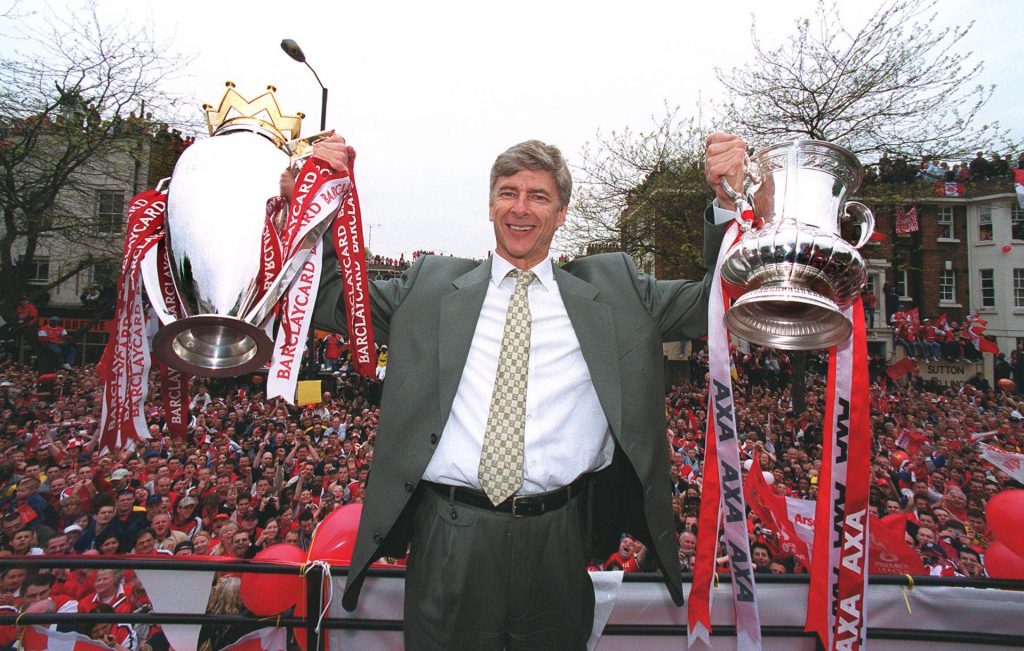

What strikes me, watching the film (I’ve only seen the version anglaise), is the Anglo-French nature of the enterprise. There are lots of establishing shots of my neighbourhood, of Highbury Fields, of the stadia old and new, of Highbury and the Emirates, of Islington Town Hall where the Arsenal team celebrate their trophies right in front of my children’s primary school, and there’s Arsene jogging through the woods in suburban Totteridge where he still partly lives, and where my parents go for their daily walks; but there’s also lots of smart Paris streets, and the little alleys of Duttlenheim where Wenger grew up and where his family work ethic was forged amid strict Catholicism of post-war rural Strasbourg. “Don’t say town, say village,” says Arsene of his roots.

The film is smartly focused on the environment around the man, an environment which he clearly affects with his achievements, his charisma and philosophy. I lived in Islington before, during and after the Wenger years at Arsenal and I can tell you that not only did the football get better, but the food improved, the coffee got nicer and the price of houses went up along with the wages and transfer fees of footballers.

“The great men absolutely impact on their time, their surroundings and on the people,” says Clarke. “I saw that with Brian Clough in Nottingham and certainly with Jack Charlton, how he altered the mood of an entire nation in Ireland. Arsene definitely altered this corner of north London, it’s architecture and its attitude.”

The fact that we are sitting in a new boutique cinema, in what used to be a fairly grotty spot behind Finsbury Park station, is evidence of that. Here’s where millions of Arsenal fans have got off trains for years and marched to the old Highbury stadium, and where, in the dark days of the 70s and 80s, pitched battles between rival hooligans would often occur – and now you can watch arthouse films and The French Dispatch.

Wenger’s arrival at Arsenal in October 1996 coincided with the rise of New Labour (the famous deal between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown took place on Upper Street) and an increasingly cosmopolitan outlook in London where an influx of Europeans chasing a slice of cool Britannia all helped alter the landscape. Under Wenger, Islington became a corner of France.

He brought in players such as Patrick Vieira (Wenger’s first signing, whom he repeatedly calls “a hell of a player”), Thierry Henry, Robert Pires, Sylvain Wiltord, Nicolas Anelka, Emmanuel Petit, as well as Remi Garde and Gilles Grimandi.

“Arsenal was like the second French team,” remembers Jeanpierre. “Every match of theirs was suddenly on French television, all the news was about Arsenal, even more than our own teams like PSG or Marseille. For the French, what was happening in London was a little miracle.”

When France won the World Cup in Paris in 1998, it felt like Arsenal had won it, too. While concentrating on the football and the manager, the film nevertheless gives a real sense of a kind of utopian immigration model, a forging of success using the underlying bedrock of the old Arsenal players (and proper lads) such as Tony Adams, Martin Keown, Lee Dixon, Ian Wright, Ray Parlour and adding European flair with the Dutch players Dennis Bergkamp and Marc Overmars and all those French guys. “You could say it was an example perfect immigration,” says Wenger in the film. “Creating something new and improved, but only by respecting local values.”

In the Q&A, he expands further. “Absolutely it changed. From 1996 it was a French influence – but after 2000 it was a multicultural team, people coming from all over the world, and English society was changing with that. Even the club Arsenal went from English owners to global ownership and that happened throughout the league – when I arrived I was the only foreign manager, but now it is hard to find many English managers and many of the clubs are globally-owned, it’s a worldwide league. It is a huge change in football and in society.”

What’s clear is that Wenger loved Arsenal, at first sight. He loved the tradition of Highbury, with its marble halls and tiny corridors and art-deco, architecturally-listed stands, and he loved the fighting spirit of English football and the long history. As he will tell us during the post-screening Q&A, he is enormously proud of the fact that he has won seven FA Cups, more than any other manager, and for a Frenchman, the FA Cup has always been “something special”, the trophy that more than any other symbolised English football.

“Until Arsene arrived at Arsenal,” says Jeanpierre, “almost the only English football we would cover on French television would be the FA Cup Final, every year. It was a famous event, so it is no surprise to us that he took it so seriously.”

But the film is mostly focused on the construction of the side that would become known as The Invincibles, Wenger’s team that went through the entire 2003-4 season undefeated on their way to the title, a feat that had never been achieved in the modern era, and has still not been matched, even by the recent imperious Liverpool, Manchester City or Chelsea teams under managers of the standing of Jurgen Klopp, Pep Guardiola and Jose Mourinho. As even Wenger’s once-bitter rival Sir Alex Ferguson finally admits in this film: “I never came close to going a whole season unbeaten, that’s an achievement on another level, that stands apart, and it belongs to Arsenal.”

As Gabriel Clarke, who secured the interview with Ferguson for the film, says: “Sir Alex pushed Arsene and Arsene certainly pushed Sir Alex and their rivalry was so intense because it kept making them want to go one better than the other. We had to have him in the film but we were a bit surprised he said Yes and surprised how he’d softened in terms of confessing to his respect for Arsene.”

The film, then, has its villain, its dramatic antagonism in the form of Fergie. It also has great jeopardy because, as is famous, Wenger states his dream of going a whole season unbeaten quite early on, during a previous unbeaten run. He is widely derided for doing so, by press and players, the former accusing him of arrogance, the latter for burdening them with such a pressure.

But Wenger, like a crazy inventor, or wild artist, a Rodin, or a Don Quixote tilting at windmills, states his intention again and prepares his players for the mental strain, to play with freedom. In many ways, the film is about the relentless pursuit of perfection, the creation of a flawless masterpiece to be sculpted out of footballers and goals.

Having confessed in the film that he would “throw up” at night after a defeat, Wenger also admits: “It was the dream of my life to convince a group to achieve something they thought was impossible.” And he goes even further in stating his ambition: “I wanted to transform football to a work of art, to make people sit in their seat and think that what they were seeing was unbelievable.”

So, when we do finally take the stage, it’s clear that with the classy, sensitive and thoughtful film Arsene Wenger: Invincible, his brand of football has indeed become a work of art. I ask him if he would call the Invincible side and their 2003-2004 season his masterpiece?

“Yes, because it means that, for a year, I did my job in a perfect way,” he concedes. “It means there was no weakness, no flaw. I think you have to give something special to people, to have ambition to do something unforgettable. And if you are audacious and you are ambitious, you can see that life can be wilder than your wildest dreams.”

So the film has got a baddie in Sir Alex and jeopardy in the tightrope moments when the precious, flawless masterpiece is in danger being dropped (the last-minute penalty miss by Ruud van Nistleroy for Man United at Old Trafford, being 1-2 down to Liverpool at Highbury before Henry takes it upon himself to dribble through) – but it is also a great love story.

It’s clear Wenger adored his Arsenal. Perhaps too much. Love at first sight became an all-consuming passion. I ask him how he would describe the relationship? “It’s a real love story that on my side will never stop,” he says, unflinching. “I arrived here at 47 years old and stayed until 69 and I gave this club the best years of my life and I’m happy for that. Arsenal loved me back and allowed me to achieve my dream and make my team with no compromises, with the values we felt were important to us, and values that will remain after me.”

However, the film doesn’t shirk from showing the bruises of that love, too, the pain of the final years when, despite more FA Cup wins in 2014, 2015 and 2017 but amid falling league table positions, the faithful crowd turned against him and the hierarchy at the club eventually felt compelled to let Arsene go at the end of the 2018 season. Although that day of “Merci Arsene”, of his final match in charge was deeply emotional for all those present, myself included – according to Wenger who kept his own emotions under some sort of control: “It was like being at my own funeral.”

In the film, he utters an extraordinary line about the Emirates stadium he, in effect, built and agitated for and which in 2005-6, with its excavations and accrued debts, physically altered the landscape of an entire area of London. Referring to the club’s former stadium, he says: “Highbury was my soul; the Emirates was my suffering.”

What a line. What a devastating sadness though. Yet I do know what he means. The move to the Emirates lessened the team financially, and although he kept Arsenal among the European elite by still qualifying for the Champions League every season, they never looked like winning another league title. But as he told the audience, the line up of players was still pretty dazzling: Robin van Persie, Cesc Fabregas, Jack Wilshire, Tomas Rosicky, Alexis Sanchez – these were wonderful footballers out of whose talents he couldn’t quite create another flawless masterpiece. There was always frailty and crashing defeat lurking.

But even despite the pain and suffering of being let go by the club whose 21st century form helped build, isn’t he still in love with Arsenal, I ask? There is a rare pause, a brief moment of composing himself. “Yes, of course, I am.” The smile returns. “I tackle, I shoot, I defend I attack, of course. My life is red and white and that will remain and, now I don’t work as a manager anymore, I can have no other commitment.”

On a footballing front, it’s rather interesting to see and hear this. Arsenal fans know Wenger has not returned to the Emirates since that last day, that so-called funeral. But tonight he speaks warmly of the future for the first time. He looks out to the audience, where current Arsenal manager (and captain of his own FA Cup winners of 2014) Mikel Arteta is a surprise attendee. “Mikel is here tonight and I have to say to him that the basis is there for the club to be successful again, a great training ground, a top stadium that is paid for, it’s all there and he has the responsibility and the possibility to make another invincible team now.”

It’s an extraordinary evening on many fronts. The audience includes not just Arsenal legends Ian Wright, Lee Dixon, David Seaman and Pat Rice but also comedians Alan Davies and Ian Stone, runner Mo Farrah, current Arsenal technical director and Invincible team member Edu. There are also celebrated managers such as former Spurs boss David Pleat and former England manager Roy Hodgson, with whom I become embroiled in a 15-minute conversation about Catherine Deneuve, Juliette Binoche and Milan Kundera.

After the Q&A, Wenger poses for pictures with everyone, displaying admirable patience and calm for someone still digesting the documentary portrait of himself, and questions about whether or not he should have a statue outside the Emirates (something to which of course he can’t answer). But the warmth with which he and Arteta greet each other and embrace in a private moment, having a long chat, was something to see. With Edu, too, suggesting rapprochement may be possible.

Full of motivational maxims and zen sayings on life, football, success and defeat, the film might well prove some kind of therapy. But the night of the premiere itself was also significant, evidence of a broken heart that might be on the mend.

For me – and I think, as viewers, we always put ourselves in the picture and find personal resonance – I couldn’t quite believe how close to this material I was. And it dawned on me on the way to the cinema. This was the summa of all my life’s experiences, a moment when all my life pathways seemed to converge. This was my last-minute penalty to win the title.

I was about to interview Arsene Wenger for a film, a discipline which has been my life since 1997. However, before that, I was a football reporter, one of the first to interview Wenger himself, before he even arrived at Arsenal. I was the first English reporter to interview Patrick Vieira, too. But I’m also a lifelong Arsenal fan, taken to Highbury in 1975 by my father who, in turn, had been taken there by his father in 1947, and my father was in the audience tonight.

I’ve also got a French degree and lived in Paris for a year, becoming obsessed with French film and French football. I even went to see Wenger’s Monaco side play. So this, in my local patch, with my family present, with my French translation skills needed for a Christian Jeanpierre, a man I’d watched host French TV shows, and with Gabriel Clarke, a British film-maker whose own father’s films had been incredibly influential on me (Alan Clarke, director of such tough classics as Scum, The Firm, Rita, Sue and Bob, Too), and with Arsene Wenger, who’d given me so many moments of joy as a fan.

Well, it was quite overwhelming as a thought when all that weighing on me. Not only that, but I’m also featured very briefly in the film, on one of my early assignments as a young reporter, having to go to the famous Highbury steps for an impromptu press conference at which the new Arsenal manager was going to defend himself against rumours that were about to surface of hideous allegations in his private life. You can spot me in small crowd of journalists that gathered there that evening.

By the reaction and conversations I overheard, the film also means just as much to so many other people who all know where they were when such a goal went in, or where they were when the team lifted the trophy.

After the Q&A, I didn’t mention that unsavoury incident on the steps again but told Arsene another story, about how, before he’d even joined Arsenal and when he was still working out his final days as manager of Nagoya Grampus 8 in Japan, a French journalist friend from sports daily L’Equipe had given me Arsene’s phone number. Sitting at the sports desk of the Daily Express, I’d called it, not expecting him to pick up, but sure enough, he did. And we had, partly in French, part in English, an excellent chat out of which I’d got a decent story for the back page. But after that he also asked me for my opinion as a respected football writer: “What should I do when I get to Arsenal? How is the team?”

I told him in no uncertain terms: “Arsene, you have to get rid of that back four,” referring to the legendary Arsenal defence including Tony Adams and Lee Dixon, that had enjoyed league titles a few years earlier under the managership of George Graham. “But they’re old now, and too slow,” I said. Arsene listened, calmly, taking all my advice in.

Of course when he arrived, he immediately made that same, ageing back four the foundation of his side, cornerstones of his first league and FA Cup double-winning team in 1998.

And that, ladies, gentlemen and Monsieur Wenger, is why, by then, I’d become a film critic.

Arsene Wenger: Invincible is in UK cinemas from 12 November and available on Blu-Ray DVD and Digital Download now