“What was I going to do? Retire? Go fishing?” says a character as they face (perhaps) – don’t worry, no spoilers here – certain death in Tom Cruise’s Mission: Impossible: The Final Reckoning. The question could just as easily be posed of the star and producer – “a Tom Cruise Production” – of this final instalment of the colon-rich, sphincter-tightening franchise.

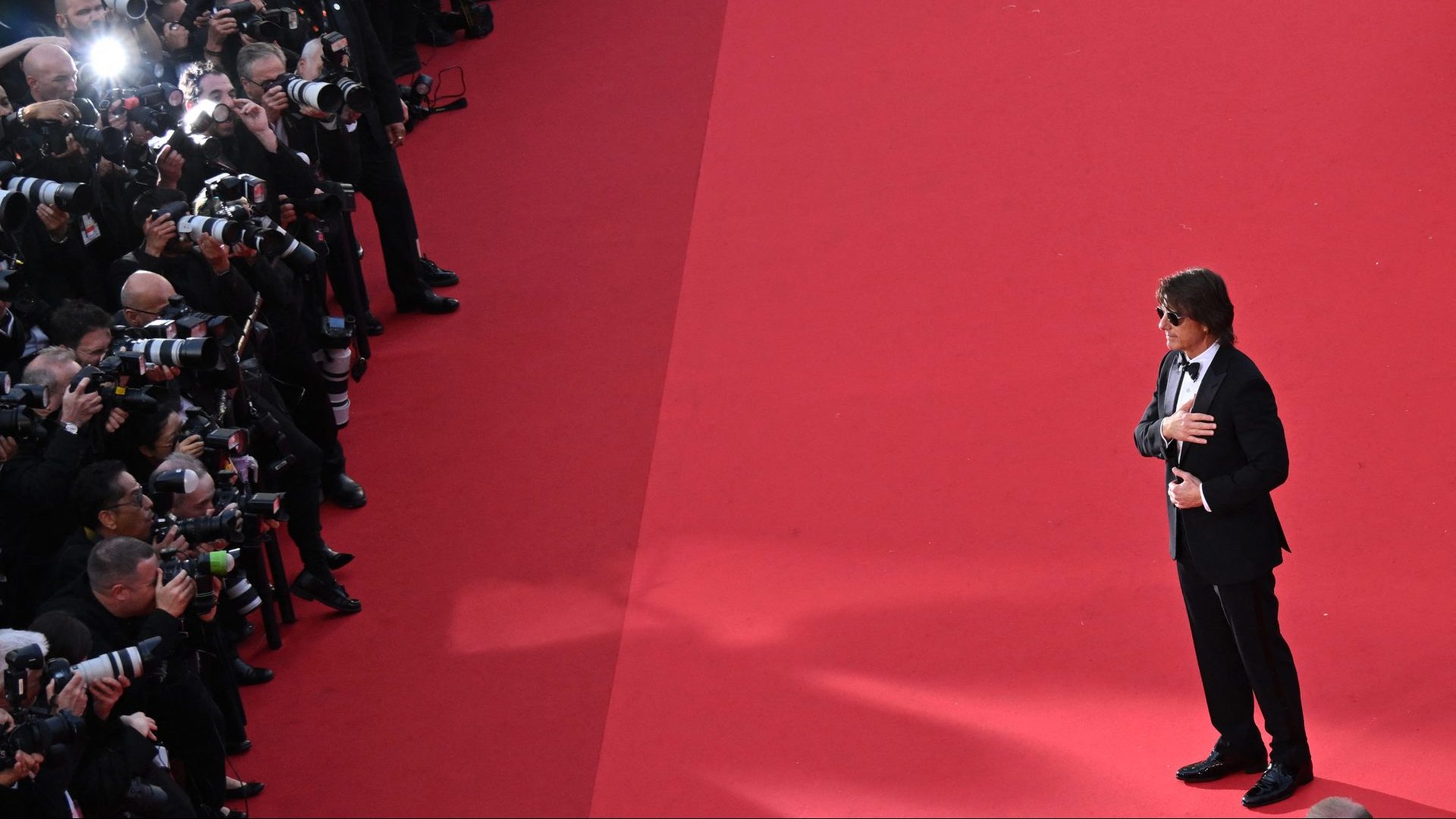

Upping the ante as ever, Tom Cruise dives to the bottom of the ocean and hangs on for dear life to a mountain-skimming prop plane, in the film that premiered at the Cannes Film Festival this week. In between, he pegs it everywhere as if he’d never heard of Uber, or impatiently listens to eleven different characters delivering a round robin of exposition, a baffling flaw in the era of show-not-tell scriptwriting.

The film hasn’t quite got the machine-tooled efficiency that gave Bond and Bourne a quite literal run for their money, and suffers end-of-franchise nostalgia – the Return of the King syndrome if you will – trying to give each of the characters their due and getting all strangely mushy about each other. I’ve always found the Mission: Impossible films to be jarringly uninvolving on an emotional level while always enjoying the kinetic daredevilry of its action sequences. The emotional depth is the kind felt at a goodbye party for an employee who’s only been with us a month.

The one exception to this might be Tom himself. Let’s be clear. I’m not going to miss Ethan Hunt. I mean, who is Ethan Hunt if not “A Tom Cruise Production” in flesh? He certainly isn’t a character. I doubt there’ll be a hunt for the new Ethan Hunt, the way there is for a new James Bond.

But I am going to miss Tom. I worry about Tom. Without Mission: Impossible, what is he going to do now? Go fishing? Surely, he’s going to need to bungee jump off the Hoover Dam or go down the Niagara Falls in a barrel of a weekend, if only to wind down from a career that has made him the most action-oriented American movie star since Buster Keaton. He’s the west’s answer to Jackie Chan, working in the tradition of a genuine heart-throb doing his own stunts, like Jean-Paul Belmondo.

And the weird thing is, Cruise’s career has been a mirror image of what it should have been, with his biggest action role in the latter half. When most actors are “too old for this shit,” it seemed like Tom was just getting started (Danny Glover was 41 when he said that line in Lethal Weapon).

In his youth, his films tended to skew comedy or dramatic. Coming out of the Brat Pack via films such as Taps (co-starring Sean Penn) and The Outsiders (co-starring the entire 1980s), Cruise first hit it big with the one-two punch of All the Right Moves and Risky Business and morphed himself by sheer will and persistence into a good actor.

A handy trick Cruise employed was to ally himself to elder co-stars as he took on the role of the upcoming and arrogant whippersnapper. In The Color of Money he was the cocky pool player, schooled by Paul Newman’s Fast Eddie. In Rain Man, he was a car salesman yuppie and Dustin Hoffman’s younger brother, who learns about autism and caring. In Cocktail, he was the acolyte to famed Australian Bryan Brown who would teach him to… make cocktails. “When he pours, he reigns,” promised the best tagline ever.

It was a sly move. Before you knew it, he was not just learning from screen legends – the end of The Color of Money gives Newman a clear advantage – he was besting them. “You can’t handle the truth!” rants a spittle-flecked Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men in 1992, but the end of the courtroom drama had a clearly triumphant Cruise handling it just fine.

Along the way, he’d notched up some of the industry’s finest directors. They included legends such as Francis Ford Coppola, Sydney Pollack, Martin Scorsese, Barry Levinson, Rob Reiner and Ridley Scott, though it was brother Tony Scott who had the biggest impact on the star’s career with 1986’s Top Gun, which gave both aviator shades and the naval flight academy a recruitment bump. Cruise’s Maverick has no identity beyond a grin and a catchphrase. Maverick, like Ethan Hunt, is essence of Cruise, this time poured into a cockpit with nary a mentor in sight. He’s an insider’s outsider. He doesn’t follow orders but accomplishes the mission, maverick in call sign only. Kelly McGillis had the thankless task of looking like she wanted to teach him something about aerodynamics.

Having dominated the latter half of the eighties, Cruise convinced doubters about his acting chops with his performance as paraplegic Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic in Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July, a heartfelt, angry side of Cruise that reminded audiences that away from sunny Reaganite power fantasies Cruise could deploy an unsuspected range.

That’s not to say that throughout Cruise’s career there haven’t been some dips and unfortunate role choices. The public’s perception has not always been of Cruise as the international treasure who rappelled into the Covid crisis to single-handedly save cinema. There was Legend for instance, an early brain fart of a role that had a lank-haired Cruise play Jack in the Green, poncing around saving unicorns from a satanic Tim Curry.

Sometimes, it was his private life that skewed the public’s perception of him. His relationship with then marriage to Nicole Kidman on the woeful Days of Thunder led to Far and Away the worst film of his career (see what I did there?) His third marriage to Katie Holmes led to a daughter and the smush-neologism of TomKat, but the break-up was acrimonious.

Over all of this was cast the strange light of his involvement with the Church of Scientology, a subject I’ve been careful to avoid lest I start getting followed by mysterious people; something which definitely wouldn’t happen. Rumours abound over his attempts to convert Hollywood greats to L Ron Hubbard’s religion as well as it having an involvement in the break up of two of his marriages. He had moments of out-of-control exuberance: he jumped up and down on Oprah’s sofa and got in Matt Lauer’s face about the terrors of psychiatry. The rumours about his sexuality led to a merciless ridiculing in an episode of South Park, something which must have been hard for a man who is always trying to be taken so seriously.

Stanley Kubrick would exploit this tendency in Cruise as well as the many ambiguities of the Cruise persona in Eyes Wide Shut, emasculating his lead to a dithering bourgeois doctor being taunted with homophobic slurs on the streets of New York and gnawingly jealous of his wife’s (Kidman) sexual fantasies. With his stardom assured and emboldened by his work with Kubrick, Cruise was in a position to move out of his comfort zone. Paul Thomas Anderson turned him into a sleazebag proto-Andrew Tate for Magnolia and Michael Mann made him a chalky-haired hitman with a rare villain role in Collateral.

But ever the canny navigator of his own career, Cruise underwrote this risk taking with a popular franchise based on a 1960s TV show. Enter Mission: Impossible. It was, to say the least, an odd choice.

The whole point of the original show was the anonymity of the cast. The characters were one dimensional agents who staged elaborate espionage jobs and heists. It had one star: the theme music by Lalo Schifrin.

Brian de Palma’s inaugural entry kept the faith of the original while promoting young Hunt (Cruise) above the mentor/adversary, played by Jon Voight. But each subsequent entry saw Cruise taking greater prominence and control.

John Woo brought his “gun fu” to the ludicrous fun of the first sequel, JJ Abrams put the train back on the tracks in his efficiently exciting follow up, and Brad Bird ushered in the first massive success of the series with Ghost Protocol.

The arrival of screenwriter/director Christopher McQuarrie saw Cruise find a partner ready to loyally serve the star and establish full Cruise control. He would go on to direct all the remaining films in the franchise including the most commercially successful: Fallout.

Final Reckoning brings together a whole mishmash of millennial apocalyptic hysteria. The adversary is called the Entity and comprises all our fears about AI, nuclear weapons, misinformation and the rise of populism into a pulsing blue graphic. “It makes our allies, enemies and our enemies, aggressors,” someone explains. So, Trump 2.0 then? Cruise’s mission (if he should choose to accept it) is to put the genie of technology back in the bottle and unite the world. Never has he been more messianic and throughout the film there is a religious fervour. A computer key is shaped as a cruciform, like something from a reliquary, and the Entity itself is referred to as the “anti-God.”

So what of Cruise himself? Having proven once more that the title was a lie, Cruise is the one we are assured who could be trusted with the total power that the Entity promises. Having saved the world numerous times on the big screen, could he be tempted to sort out the world’s problem via political office?

After President Reagan, Governor Schwarzenegger, Trump I & II, would Cruise fancy running – in his inimitable arms pumping style – for the White House? Given the popularising of so many marginal crackpot ideas, Scientology might not be the dealbreaker it once was.

Think about it: President Tom Cruise. Perhaps unlikely, but not impossible.

John Bleasdale is a writer, film journalist and novelist based in Italy