It’s one of those moments that comes periodically in Cannes. You watch a film that exposes the inequalities of the world, the injustices, or the instances of oppression and unfairness. You witness the marginalised and those left behind in films by the Dardenne brothers and Ken Loach, or the extravagant awful rich being pilloried in Ruben Ostlund’s The Square or Triangle of Sadness or (both of which won the Palme d’Or), and you step out onto the Croisette, next to the Casino, opposite high-end shops of brands such as Prada and Dolce & Gabbana.

The cognitive dissonance is to be savoured or it will drive you mad. Film critics from all over the world sit in darkened rooms and watch tales of despair and desperation while outside super yachts sleep in the harbor, rocking gently on the Mediterranean tide.

This year the disparity between the reality of the world and irreality of the cinema and sometimes those two states switch places. War in Ukraine continues with several films devoted to the conflict playing at the festival – all from the Ukrainian perspective – and there is once more no Russian pavilion in the international village. The director of the festival, Thierry Fremaux was even moved to introduce the very Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov as “no longer a Russian director” when introducing his film The Disappearance of Josef Mengele.

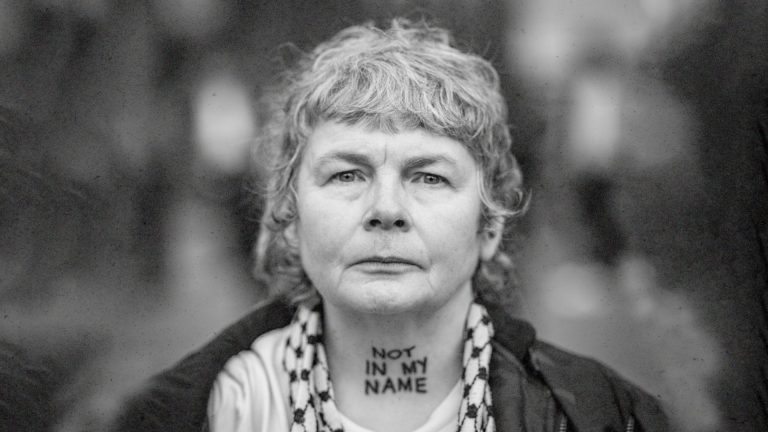

When it comes to the ongoing conflict in Gaza, the official stance of the festival has been much more muted and both sides-y. There is an Israeli pavilion and an Israeli film, Yes! by Nadav Lapid. At the beginning of the festival, a letter was published with hundreds of signatories from the world of film condemning Israel’s ongoing killing of the population of Gaza, many of whom are women and children and innocent men.

Suggested Reading

Misan Harriman: A lens on a world in protest

From the stage of the opening ceremony, tribute was paid to Fatma Hassona, the Palestinian photographer whose life is the subject of a film showing at the festival – Sepideh Farsi’s Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk – and who was killed in April of this year. She should have been here for the film’s premiere. Instead, along with six members of her family, she was killed in the house where she slept by an Israeli air strike. No contrast can be more stark.

More of that in a moment. The other film Once Upon a Time in Gaza is a film that bases its resistance in its very normality. Shot in Jordan by the Nasser brothers, Arab and Tarzan Nasser, it is a lo-fi crime movie with a slow burn pace and a nice line in meta-fiction as a man desperate to escape Gaza and a life of semi-criminality finds himself picked off the street to star as in a Hamas inspired TV show called “The Rebel.” It has more of Nicholas Winding Refn’s Pusher trilogy than the Sergio Leone or Quentin Tarantino films hinted at in the title.

But it’s punctuated by explosions as drones and missiles strike the city from Israel. “Making a film is resistance,” the hero is told and although there’s an irony to the point – after all it’s a Hamas representative who is saying this – it’s also true. The normality of a crime film is a stubborn refusal to have artistic expression always react to the actions of the oppressor.

The Nasser brothers aspire to a genre of filmmaking which will allow their work to escape the spiral of violence even as it explores it. It aspires to a certain slickness, which contrasts with the rawness of Sepideh Farsi’s Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk. The title comes from Fatma’s uncorrected English as she describes what it feels like to step into the streets of Gaza.

The film is basically a series of video calls between Sepideh and Fatma, occasionally broken by a news report or a political speech which gives context – although this in itself is not given without an obvious bias. The Iranian filmmaker and the Palestinian photographer bond over the months despite the fact that their lives are completely different.

Sepideh, like us, lives in a privileged space where bombs don’t fall. She travels freely to film festivals. She has a nice apartment and a cat who demands her attention, and as much as she sympathises with Fatma, she can’t help sounding a bit impatient when the connection on the call is interrupted. We see her face reflected on the screen.

Fatma on the other hand is a young 24-year-old photographer who is moving from apartment to apartment and might be calling from a bomb shelter. Her belongings can be gathered in a puddle of shopping bags. She has family members who pop into view to wave and a radiant smile.

Rather than being furious or despairing, she reassures Sepideh constantly that she’s okay. At one point, Fatma spends half the phone calls reassuring Sepideh not only that she’s okay but that she values these connections. “But there’s nothing I can do for you,” Sepideh says. “I can’t send you anything.” “But you’re here with me,” replies Fatma, and delivers another of her warm generous smiles.

And in between all of this are the photographs which Fatma takes. Images of devastation which we look at now but see anew looking through Fatma’s eyes. There’s a sense of immunity that is given to people who are looked at – looking is an expression of care, after all we “look” after people.

When Fatma doesn’t reply to her phone, it feels like an awful moment. But it gets worse. In the final conversation, she is told that the film has been accepted for the Cannes Film Festival and arrangements are being made for her to leave Gaza and attend the festival. She is delighted, but also determined to return. “My family and life are here,” she says.

For all our looking, for all our bearing witness, the Israeli bomb still killed her and her family; and there’s not much left to say about that.