More years ago than I care to count, I spent what for me qualifies as a happy afternoon – in the library of the Imperial War Museum, looking at trade figures. And I found something that intrigued me.

It was a simple set of numbers that looked, at first glance, impossible. But when I delved deeper, a set of numbers that revealed an extraordinary story of wartime smuggling, at huge risk, that went some way to saving Britain from the Nazis.

I had been researching a story about the final payments made by the British government to Washington DC for the Lend Lease loans given to us during WWII so we could buy US government supplies and munitions from America. The table of figures I came across was for UK imports from Switzerland during the 1940s.

These showed, as you would expect, that Britain’s capacity to bring in goods from Switzerland fell off a cliff in June 1940, after the fall of France. But then in the years before D-Day, Swiss imports to Britain rose.

How could this possibly happen? After the fall of France, Switzerland was surrounded by Axis powers, including the new Vichy government. These powers – or more accurately, Germany – had pretty much total control over all Swiss exports and imports. There were no flights between the UK and Switzerland.

And yet the UK imported significant amounts of Swiss goods throughout this period.

The answer, as I discovered, was because of Operation Danegeld, a giant smuggling operation organised and run by the British government’s Ministry of Economic Warfare. It was a vital and top-secret operation because the Swiss and only the Swiss made dozens of things without which Britain’s wartime economy would have almost ground to a halt.

For a start, the Royal Navy, the RAF and the Army needed vast numbers of binoculars, range finders, theodolites (which measure angles horizontally and vertically), cameras and most of all chronometers. These are highly accurate and reliable watches which greatly aid navigation at sea, and often in the air. Chronographs, very accurate stopwatches, were also needed in huge number for clockwork fuses and timing artillery barrages.

The UK required thousands and thousands of such items and its allies even more, Switzerland wasn’t the only source of them – just the best and most important one.

The Swiss had also, because of their watchmaking industry, developed the most precise machine tools available. Amazingly accurate and delicate lathes, cutters, milling machines, planes and drills, amongst many others. Just the kind of machinery needed to make gun barrels, engine parts, aircraft, and high-precision components for almost every kind of weapon.

Many of these tools were as big as a van, some as large as a lorry. But a way had to be found to get them back to the UK.

But that was not all. The Allied forces used artillery and anti-aircraft shells in their millions every year and all needed fuses so that they exploded just before they hit the ground, or came close to an enemy aircraft. That meant very accurate fuses and very accurate fuse wire.

And naturally, Swiss machine tools to make fuses and their components including wire makers were the best in the world. The precision wire for the fuses was also used to make heated clothing for aircrew.

The Swiss also produced jewelled movements and bearings, the microchips of the time. Minute and often handmade, using emeralds, diamond dust and other precious stones to cut friction to a minimum, they were used in watches and chronometers and just about every meter and gauge produced. An aeroplane, with its engine heat monitors, airspeed indicators, altimeters and a dozen other instruments, couldn’t be built without them.

Jewelled movements and bearings could withstand huge pressure and temperature changes and remain accurate, an essential characteristic in wartime. The skill and detail involved was immense; Swiss industry boasted that its workers could drill a hole smaller than a human hair into the head of a pin, hollow out the head, line it with diamond dust and use it to make a microscopically small axle or pivot – and all by hand.

The Allies needed millions of movement and bearings, as well as miniature screws, nuts, wire, dies and ball bearings, the Swiss had a virtual monopoly on the lot.

All this too needed to come from Switzerland somehow. Not only that, but Switzerland didn’t mine any precious stones itself, so the raw material had first to be smuggled into Switzerland and then the finished goods smuggled out.

The problem was even worse for diamond dies, made of the precious stone and used for drawing fine wire from hard metal. These were crucial to advanced manufacturing, but the dies were made on the French side of the Jura mountains.

So the diamonds had to be smuggled into Switzerland, then into occupied France (along with gold to pay the producers), and then the dies had to be smuggled back into Switzerland and finally back to the UK.

Organising the logistics of all this was a daunting prospect.

In the summer of 1941, an amazing car journey took place. A 44-year-old British man, his French wife, their maid, their five-year-old son and the family dog, drove from Spain across occupied France to Switzerland.

Carrying an emergency supply of tinned goods, they passed seamlessly through occupied France, barely delayed by French Gendarmes and passing easily through checkpoints. They stayed in hotels and dined in restaurants stuffed full of German officers without raising an eyebrow. In the middle of the second world war, this might seem like an impossible journey but for John Lomax, it was a piece of cake.

The secret of Lomax’s success was that he enjoyed diplomatic immunity, and this was something he took full advantage of. Lomax and his family were on their way to Berne, where he was to be the new commercial attaché at the British embassy.

Even in the middle of the bitterest, most costly and deadly war in history diplomatic conventions were still respected; Lomax and his family needed to get to neutral Switzerland, just as German diplomats needed to get to Mexico or Argentina and so they were given permission to travel across occupied Europe.

Even so, Lomax pushed his luck. The convention was that such journeys be made by train and that they should not take longer than 24 hours. Yet he drove, a journey taking three days, and he did not waste a minute.

At the Franco-Spanish border, the dog got free and ran riot through the garden of the French Customs chief, terrifying his chickens. John Lomax offered compensation in the form of a tin of cigarettes, a slab of chocolate and a $10 note. All three were worth their weight in gold in war-torn Europe and pretty soon the head of customs was offering to “assist with any little transactions” if he could.

He would over the next three years help many a “traveller” working for John Lomax and was always rewarded with a tin of cigarettes, a slab of chocolate and a $10 note.

Lomax completed his journey with ease, but had the Vichy and especially the Nazis regimes known what his real mission was, they would doubtless have made a real effort to prevent him ever making it to Berne.

The National Portrait Gallery has a picture of a rather stuffy and stiff-looking Sir John Lomax from the 1950s in full ambassadorial regalia. He looks something like Captain Mainwaring. But far from being stuffy, self-important or rule-bound, Lomax was dynamic, determined, ruthless and very efficient.

Lomax wanted to become a doctor after distinguished service during the first world war, which included winning the Military Cross. But his injuries prevented him from doing this and instead he joined the Consular Service of the Foreign Office.

The Consular Service was the commercial arm of the Foreign Office, and Lomax therefore spent years being looked down on by diplomats and their wives as a mere “trader”. But by the beginning of the second world war, he had become an expert on the finer points of international trade, including tariffs, embargoes, and even, as he freely admitted himself, bribery and corruption.

With Switzerland now surrounded by Nazi Germany and its allies and with all flights banned for the duration, smuggling was the only way of getting goods to the UK. So, John Lomax after a career spent encouraging foreign countries to open up their markets to British goods, was now told to smuggle millions of pounds worth of goods across occupied Europe, without the Swiss, the French and most importantly the Germans finding out what was going on.

The obvious solution was to create a smuggling route from Geneva across France to neutral Spain and then onto the UK via Portugal. Lomax was not the first to run the operation or the last but he is the only one to have written a book about it, and it is Boy’s Own stuff.

Lomax set about his task with verve. He recruited young men and women stranded in Switzerland by the war, bought up production from Swiss watch factories, smuggled in diamond dust and millions of pounds worth of precious stones via the diplomatic bags and found a woman to smuggle them across the border into France and back again.

He then used the diplomatic bags of sympathetic states (and the Swiss, although they were totally ignorant of the fact) to smuggle jewelled movements into the UK, often through friendly junior officials who did not bother to tell their ambassadors. Sometimes, they were hidden in newspapers posted home – but only Axis newspapers, which no one wanted to steal.

Smugglers were paid to hide jewelled movements and watches in their luggage and cars. Officials along the route from Switzerland to Spain were bribed relentlessly. Depots were set up in Vichy France, and Spanish border guards who caught smugglers coming into Spain knew to visit the British consulate in Barcelona to deliver the seized contraband – in return for payment, of course.

Motor gears essential for the RN’s fleet of motor Torpedo Boats were disguised as innocent record players, and Lomax’s team became experts at forgery, fraud and corruption. Placing orders through invented companies in Latin America, via friendly Italians or even issuing forged German export certificates themselves; they arranged the export of Swiss machinery which never arrived at its destination.

These had been “unfortunately” seized by the Royal Navy at sea, or stolen in Gibraltar or somehow got “lost” the second they were out of Switzerland.

The scale of the operation was so huge that it is impossible to think the Swiss didn’t notice that a massive amount of their most sophisticated industrial production seemed to be disappearing into thin air. They obviously decided to turn a blind eye to the whole affair.

The operation was so smooth and well organised that John Lomax claimed it was actually cheaper than shipping the goods in peacetime. Bribery and corruption oiled the wheels, patriotic men and women risked their lives to keep the smuggling routes open and so did some very well-paid rogues, crooks and thieves.

In his book Diplomatic Smuggler, Lomax even claims that one such smuggler who tried to blackmail him was assassinated by a Free French agent parachuted into Occupied France. Nothing was to stand in the way of the smuggling route.

The smuggling of millions of small components such as jewelled movements, watches and dies was one thing but British industry also needed whole machine tools as well. Some of these were huge and British industry needed a lot of them. Lathes, milling machines, drilling machinery and many others, of supreme accuracy, had to be smuggled out of Switzerland.

The answer was once again the diplomatic bag, but not the almost daily delivery of papers and documents under diplomatic immunity. Diplomats change posting regularly and all their families’ property, from furniture to clothes and cars was – and still is – transported with complete immunity. In the 1940s this was done by sealed railway cars.

Lomax and his team cajoled and bribed diplomats from supposedly neutral counties to include heavy equipment like lathes in the railroad cars that they were using to take their belongings out of Switzerland and across France. On other occasions, they just broke into the trains and hid their machinery. They then re-opened the cars in Spain and resealed them after reclaiming their contraband.

The British government, of course, had to create a list of the most important equipment that was needed immediately. So the diplomatic smugglers in Berne were always hurrying to find ways of getting the latest piece of essential new machinery to the UK as soon as possible.

One of the most essential was the measuring machinery that only the Swiss produced. It is after all not only essential in wartime to produce equipment to the highest standards, but you also have to be able to check it is good enough. To do, that Swiss equipment was essential.

The idea that much of British industry and the armed forces were dependent on foreign and especially Swiss technology might seem like a state secret of the highest order. But it is perfectly obvious that it was a well-known fact even during the war and the evidence for that can be found on the cinema screen. At least two films of the time were about just this subject.

The Foreman Went To France told the true story of Melbourne Jones. Realising that France was about to fall, he went to the continent to bring back some absolutely vital, Swiss-made machine tools, for drilling gun barrels.

The second film was Sherlock Holmes And The Secret Weapon, in which Holmes and Watson travel to Switzerland to foil a Nazis plot and rescue a Swiss engineer who has developed a top-secret and highly accurate bomb sight.

This high-tech design is so secret that the engineer divides it into four parts which only four different Swiss engineers, based in London, are allowed to make. What is interesting is that it is openly admitted in the film that only Swiss engineering and engineers are good enough for the job. This contains a large element of truth, as often it was necessary to not only smuggle machinery out of Switzerland but also the Swiss engineers to make it work.

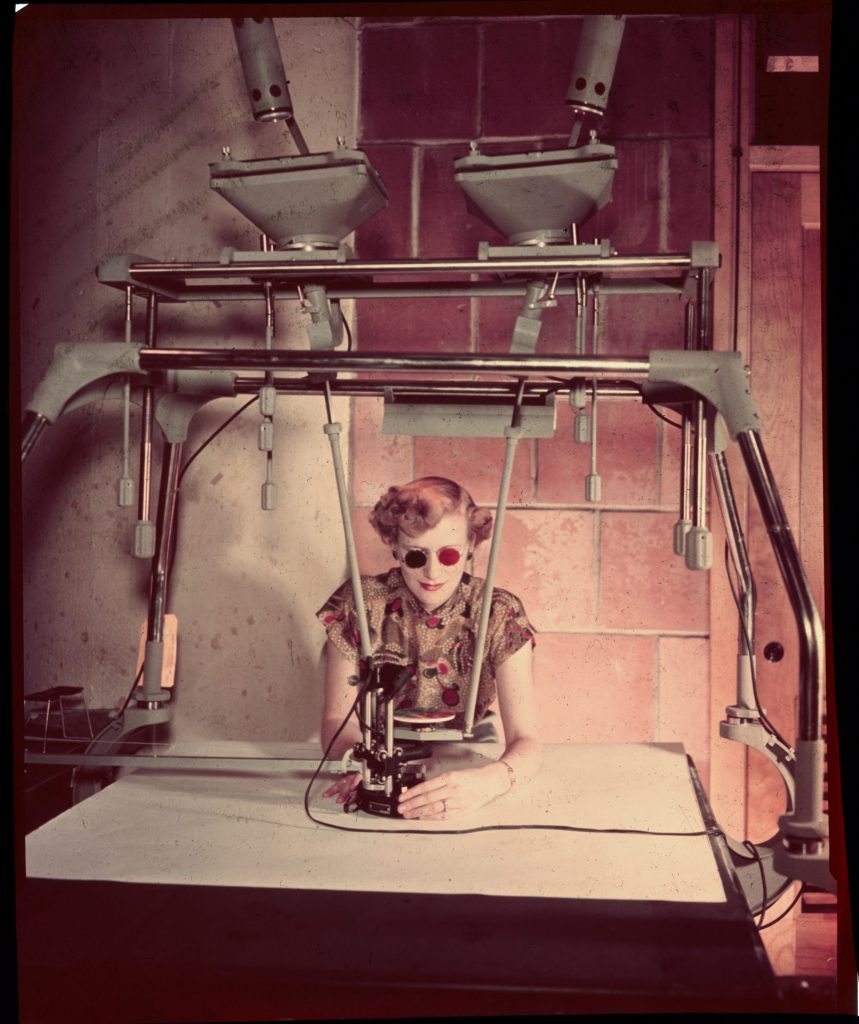

There was, however, also demand for equipment of more direct use to the war effort, than machine tools, jewelled movements and watches. The best example is not a fictional bomb sight but something almost as important to the RAF – the Wild stereoscopic plotter. A large machine, weighing three tons and originally designed to enable better map-making, it was the only optical machinery capable of turning oblique aerial photos into usable, very accurate images.

The UK had only two of them and they were working 24/7, 365 days a year not making maps but analysing aerial reconnaissance photographs. It was the Wild plotter that was used to identify the V1 rockets being tested at Peenemunde on the German Baltic coast, which was subsequently heavily bombed by the RAF, in an attempt to slow down its development.

The RAF and nearly everyone else was desperate for more Wild stereoplotters but the Germans knew that this piece of hi-tech equipment was of vital use to the Allies and kept an eagle eye on production. Attempts to order a new one “on behalf of” a South American government failed, so did bribing existing owners to demand new parts and repaired components, or at least enough to recreate a whole new projector.

Then a Luftwaffe raid on Southampton severely damaged one of the two Wild plotters in the UK. The smuggling of a new machine had to go to the top of the list.

The solution was ingenious. A Portuguese company was “persuaded” to order one and the Germans approved its export, but only on the grounds that the machine never left Portugal. So, in a scenario familiar to fans of Trigger’s broom in Only Fools And Horses, the machine’s essential parts were stripped and sent to the UK, where they were used to repair the damaged plotter.

The Portuguese, meanwhile, sent back bogus parts to Switzerland for repair claiming they had been “damaged in transit”. The Swiss manufacturer connived in the fraud by destroying the obviously fake parts and supplying new genuine ones.

Later in the war, several other Wild plotters were acquired via Portugal and another two were shipped all the way across Nazi Germany to Sweden and finally sent to the UK. The same route was also used to smuggle essential Swedish high-tech engineering products to the UK, including specialist metals and ball bearings. The Swedes used high-speed ships and Mosquito bombers, which were also used to get the Danish nuclear physicist Nils Bohr to the UK.

The Wild plotters arrived in time to assess the defences of Normandy before D-Day, saving many lives. It was just another example of the huge importance of the smuggling operations from Switzerland through occupied Europe.

Professor Neville Wylie of Sterling University, regarded as the leading expert on Operation Danegeld, quotes Dingle Foot, the effective head of the Ministry of Economic Warfare, as saying that the Danegeld operations were “one of the great achievements of the war”.

Only 1% of the essential supplies smuggled out of Switzerland were lost in transit and since the goods were sold to UK firms the operation sometimes made a profit.

Towards the end of the war Winston Churchill demanded and was presented with a full report on Operation Danegold, including the history of Swiss watchmaking and a full list of the machinery, components and vital equipment that had made its way to the Allies (attached).

That document is still held by the National Archives in Kew. It has been suggested that Churchill’s decision to be gentle with Switzerland after the war despite the fact that economy did far more to support the Nazi war effort than the British one – and despite its hoarding of large amounts of Nazis gold – might be because he was acutely aware of how much Britain’s war effort had been dependent on the Swiss government turning a blind eye to Operation Danegeld.

As for John Lomax, he became Sir John and reached, as he joked, the very heights of the diplomatic service, as HM Ambassador to Bolivia; home of the highest capital city in the world.

Small reward you might think for such a huge contribution to the British war effort. But quite an achievement for mere “trade”.