“I am Salomon from London and I have come to fetch you.”

In December 1790, Joseph Haydn was 58 years old, famous throughout Europe, newly returned to Vienna and ready for a new challenge. Over nearly three decades he’d constructed a formidable reputation as Kapellmeister, master of music, in the service of the noble Austrian Esterházy family, composing the bulk of the works that make up one of the greatest career oeuvres in the history of music.

The elderly Prince Nikolaus had died at the end of September and it was well-known that his son Prince Anton had no interest in music. Indeed, the orchestra of the court was disbanded within hours of Nikolaus’ death and while Haydn kept his job title and would receive a retainer thanks to the musical prestige his name brought to the family, he was free of obligation and effectively available for hire.

His release from his Esterházy commitment also meant he could return to his beloved Vienna. Prominent aristocrats though they were, the main estate was in rural Hungary, a backwater where Nikolaus kept his highly-prized director of music squirrelled away from the city with its predatory impresarios and rival noble families.

Vienna was where Haydn had received his musical education. The son of a wheelwright from rural Austria, he’d been apprenticed aged six to a choirmaster uncle before being selected for the choir at St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, where among other things he sang at Vivaldi’s funeral in 1741.

Flogged and expelled in 1749 for snipping off the ponytail of a fellow chorister, Haydn embarked on a perilous career as a freelance musician and composer, occasionally singing in the streets for coins as well as teaching and working as an accompanist. His reputation in the city grew throughout the 1750s until he left for the court at Esterházy in 1761.

Lodging with his friend Johann Nepomuk Hamberger, Haydn looked forward to immersing himself again in the place he regarded as home, revisiting a few old haunts, re-establishing old friendships and attuning himself to musical life in the music capital of Europe. Financially secure even if not strictly wealthy, he foresaw a gentle progression towards a pleasant Viennese retirement.

Then, on that chilly December day, Johann Peter Salomon knocked on the door, announced himself and his intention to transport Haydn to London, and everything changed.

For all the years he’d worked away happily for the princes of Esterházy, Haydn had little or no idea just how far his music had spread. He had occasionally requested permission from Nikolaus to travel abroad, proposals his canny employer would dismiss with a handful of gold coins and the words, “Ah Joseph, it’s far too dangerous out there for a sensitive soul like you”, but he was as unworldly as it was possible to be. Meanwhile his symphonies, operas and string quartets were performed to wild acclaim across the continent, particularly in London where, among many others, King George III himself was a fan.

As Salomon, a German-born violinist and concert promoter based in London, elaborated on his proposition it began to dawn on the composer just how famous he might actually be. Indeed, when he heard how much money was on the table in return for an opera, six symphonies and 20 other orchestral pieces, Haydn had to stop himself running upstairs to start packing immediately. When his friend Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart later pointed out that he didn’t speak a word of English, Haydn chuckled, “That’s as maybe, but my language is understood throughout the world”.

The deal was signed and on 15 December Haydn and Salomon set off for London, travelling via Munich and Bonn (where he met a young Ludwig van Beethoven, to whom he would later become a mentor) before arriving at Dover on New Year’s Day 1791 after a rough crossing, the composer congratulating himself in his journal on not being sick.

In London, where he took rooms on Great Pulteney Street, Haydn was greeted as a major celebrity even in the vibrant city of William Pitt the Younger, Edmund Burke, Joshua Reynolds and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. The newspapers followed his every move, Oxford University presented him with an honorary degree and each day brought new invitations to balls, concerts, salons and the homes of the great and the good.

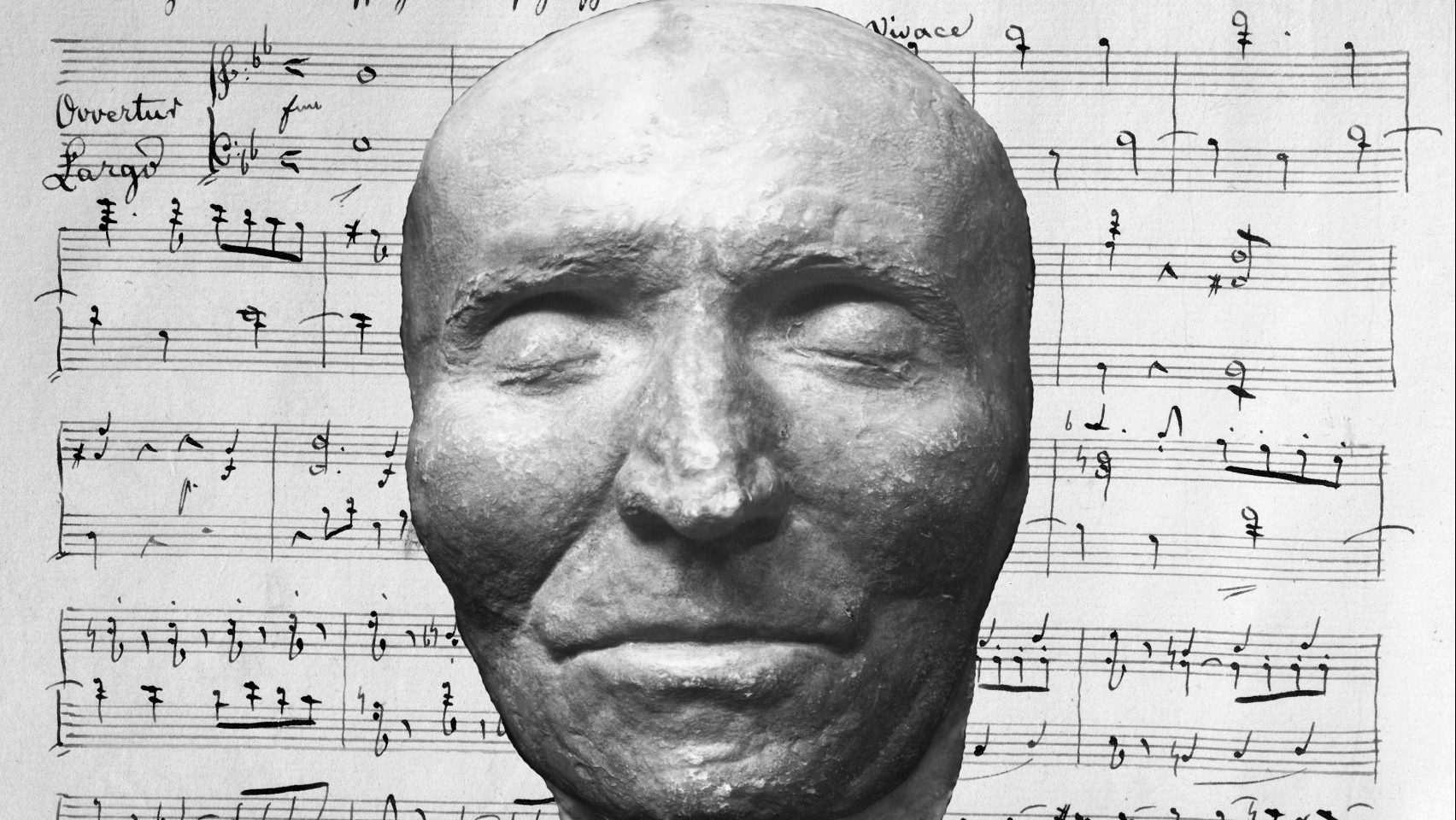

Within barely a fortnight of his arrival, Haydn had met the Prince of Wales, the future George IV, who would become his patron during his time in London. When the king first set eyes on the composer he rushed over to greet him without waiting for the formality of an introduction. It was all quite something for a smallpox-scarred son of a wheelwright who’d spent almost his entire career as a court musician and composer in the Austro-Hungarian provinces.

“My arrival caused a great sensation throughout the whole city, and I went the rounds of all the newspapers for three successive days,” he wrote in his first letter home. “Everyone wants to know me. I’ve had to dine out six times up to now, and if I wanted, I could dine out every day.”

When he attended his first concert in London the man who, during his career, had occasionally played in return for cabbages, candles and, on one occasion, a live pig, wrote, “I was conducted, on the arm of an entrepreneur up the centre of the hall to the front of the orchestra, amid universal applause, and there I was stared at and greeted by a great number of English compliments. I was assured that such honours had not been conferred on anyone in 50 years”.

The musician and writer Charles Burney recorded of Haydn’s first concert performance that, “Haydn himself presided at the pianoforte; and the sight of that renowned composer so electrified the audience as to excite an attention and a pleasure superior to any that had ever been caused by instrumental music in England”.

Haydn was revitalised by London and produced some of his finest work in his four years based in the city before returning to Vienna in 1795 to enjoy his wealth and celebrity in the place he loved most.

Underrated today among the likes of Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, the quality of Haydn’s prolific output and his influence on European classical music is immense. No classical composer has mastered so many genres, from revolutionising the string quartet to earning his status as ‘the Father of the Symphony’. Not only that, throughout his career he never lost sight of the sheer joy that music could bring. It flowed out of him to the extent that late in life he described with a chuckle how his imagination “played upon me as if I was a clavier. Indeed, I am really just a living clavier”.

He even brought happiness to the ailing John Keats, who in the last days of his life in 1821, knowing he was dying, requested a musician friend play Haydn’s works for him on the piano.

“This Haydn is like a child,” the poet said, “for there is no knowing what he will do next.”