The first world war was only a few days old in August 1914 when military police knocked at the door of a Blackpool boarding house frequented by touring entertainers and circus performers.

Their quarry was not the Webb Brothers, tumblers of note whose act included turning somersaults while playing concertinas, but the man sharing their accommodation, an acrobat of impressive physique who had the misfortune to be German.

Joseph Pilates had arrived in Britain in 1912 on the brink of his 30s, hoping to establish himself as a professional boxer. Yet a combination of relatively advanced years and a grasp of English that was barely rudimentary saw him finding alternative employment as a circus performer.

When war broke out, being an itinerant German relatively new in the country popping up at various coastal locations that summer, Pilates found himself an early victim of the Alien Restriction Order. He became one of the first Germans in Britain to be interned.

When the knock came he was expecting it, having already had to register with the local police station and noticed the suspicious looks he was receiving from the officers behind the desk. When he mentioned he had worked briefly in London as a fitness consultant inside Scotland Yard it only increased rather than diminished the doubts among officialdom.

As he was marched away up a Blackpool side street between two grim-faced policemen, amid the happy sounds of a resort enjoying a last innocent summer before the reality of war kicked in, it was a rare moment in Pilates’s life when he didn’t feel entirely in control of his own destiny.

The feeling would have soon passed. Pilates was a man who had never been blighted by self-doubt and had been convinced he was going to make a difference to the world from an early age. The only question was how.

Remarkably, internment provided the perfect conditions for him to develop and hone the exercise and health regimes that would make his name famous around the world. After all, if he could transform himself using the techniques he had devised, then anyone could achieve the same results.

The son of a Greek father and German mother, Pilates’s Mönchengladbach childhood was blighted by asthma and rickets. Instead of succumbing to his ailments, he took up bodybuilding at 13 determined to improve his health, and within a year was being used as a model for anatomical charts. Relentlessly curious about how the human body worked, he expanded his self-improvement regime into martial arts, yoga and Zen meditation. Pilates soon concluded that the main drivers of poor health were bad posture, inefficient breathing and the increasingly sedentary lifestyle of the 20th century.

None of this mattered to the military police, of course. Pilates was taken from Blackpool to Sandhurst for questioning before being sent first to a prison camp in Jersey, and then to a disused barracks in Lancaster. There he set about devising keep-fit and conditioning classes for his fellow inmates, recognising how the disillusion and melancholy that went with imprisonment could be alleviated by a mixture of positive thinking and physical exercise.

By the time he was transferred to the Knockaloe camp near Peel on the Isle of Man in 1915, Pilates had planted the seeds of what he called “contrology”, a method by which the mind is trained to have complete control over the body, focusing on the core muscles governing posture, balance and support for the spine while maintaining an awareness of the importance of breathing.

Pilates spent the entire war interned and was not released until the spring of 1919. During the four-and-a-half years he spent behind the wire he was able to refine his theories, put them into practice and see their clear health benefits despite having little access to equipment.

“Not one prisoner in that camp who followed my exercise system faithfully came down with the Spanish flu even when the epidemic was sweeping England and the world,” he would boast for the rest of his life.

Released in March 1919, instead of being free to continue his life in Britain Pilates was sent to a processing centre at Alexandra Palace, before being repatriated to a Germany he had not seen in seven years and barely recognised.

He arrived in a very different country to the one he had left, a nation defeated and humiliated. He settled in Hamburg and found work helping to train police officers as well as finding the nation’s dance troupes receptive to his methods – modern dance pioneer Rudolf Laban was an enthusiastic adopter of the Pilates programme – but by the mid-1920s he could see the direction in which Germany was heading, and he didn’t like it.

During the summer of 1926, he boarded the liner Westphalia at Hamburg and headed for a new life in the US, meeting his future wife, Clara, on the voyage.

Before long Pilates had opened a studio and gymnasium on Eighth Avenue in Manhattan that soon became a magnet for dancers and performers. He came to wider public attention in 1931 through his work with the heavyweight boxer Charley Massera. Sidelined from the ring for three months with a broken hand, Massera was sent to Pilates for fitness conditioning, achieving dramatic improvements in how he took a punch to the body that impressed even one of the greatest fighters who ever entered the ring.

“Massera hardened his muscles to such extent that he could take a solid wallop from Jack Dempsey without flinching,” said the Daily Republican. “Dempsey remarked, ‘who’s the kid? Boy, can he take it.’”

Word spread throughout New York and beyond, allowing Pilates to build a roster of celebrity clients that ranged from Yehudi Menuhin to Peggy Guggenheim to Katharine Hepburn, perfecting the techniques that would survive him and conquer the 21st-century world.

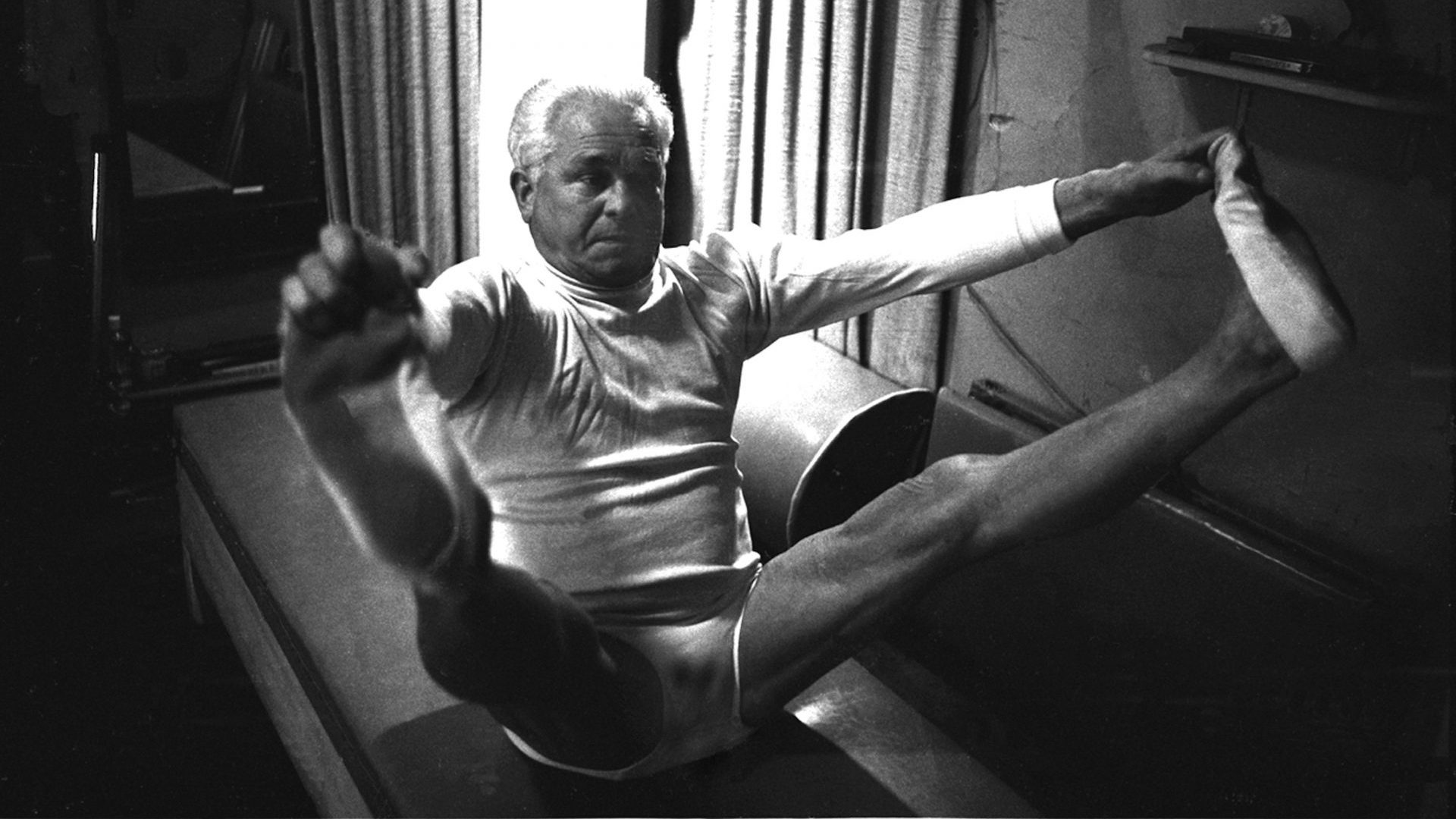

“I picked up my knowledge as a child,” he told an interviewer in 1963 while demonstrating he could still bend to touch the floor with his elbows at the age of 82. “I watched men at work and play; then I watched animals, both domestic and wild, in and out of the zoo. I soon discovered that animals had the best system of all for keeping fit. You never see a big cat out of shape or in poor physical trim.”

It all sounds obvious to us today, but the mark of genius is making the greatest ideas seem commonplace. Pilates’s methods were developed under the most trying circumstances; a journey that began with a knock on the door in an unfamiliar town in an unfamiliar country and a rare, possibly unique moment of uncertainty in a man who was always certain.