It was “a record so inane and infuriatingly catchy that it had to be a hit,” according to the Guardian. The Daily Mail went even further. “If you have been tasteless enough to buy the ridiculous Trio single Da Da Da,” it sneered, “then you are probably to blame for the release of their album.”

Yet 13m sales worldwide suggest that, in 1982 at least, inane, infuriatingly catchy and ridiculous was a winning musical combination. The song by the German new wave outfit was a global sensation, its simple structure – deadpan lyrics over a tinny backing track provided by a hand-held Casio synthesiser – lodging in listeners’ minds enough for them to push the single high up the charts in more than 30 countries.

In Britain, Da Da Da reached no 2 in the charts, ahead of Japan, Visage and Bucks Fizz, and was kept off the top spot only by Irene Cara’s bombastic theme from Fame. Towards the end of the 1980s the song got a second life in the UK when it was parodied in an advert for the washing-machine firm Ariston, accompanied by a stop-motion video made partly by Aardman Animations.

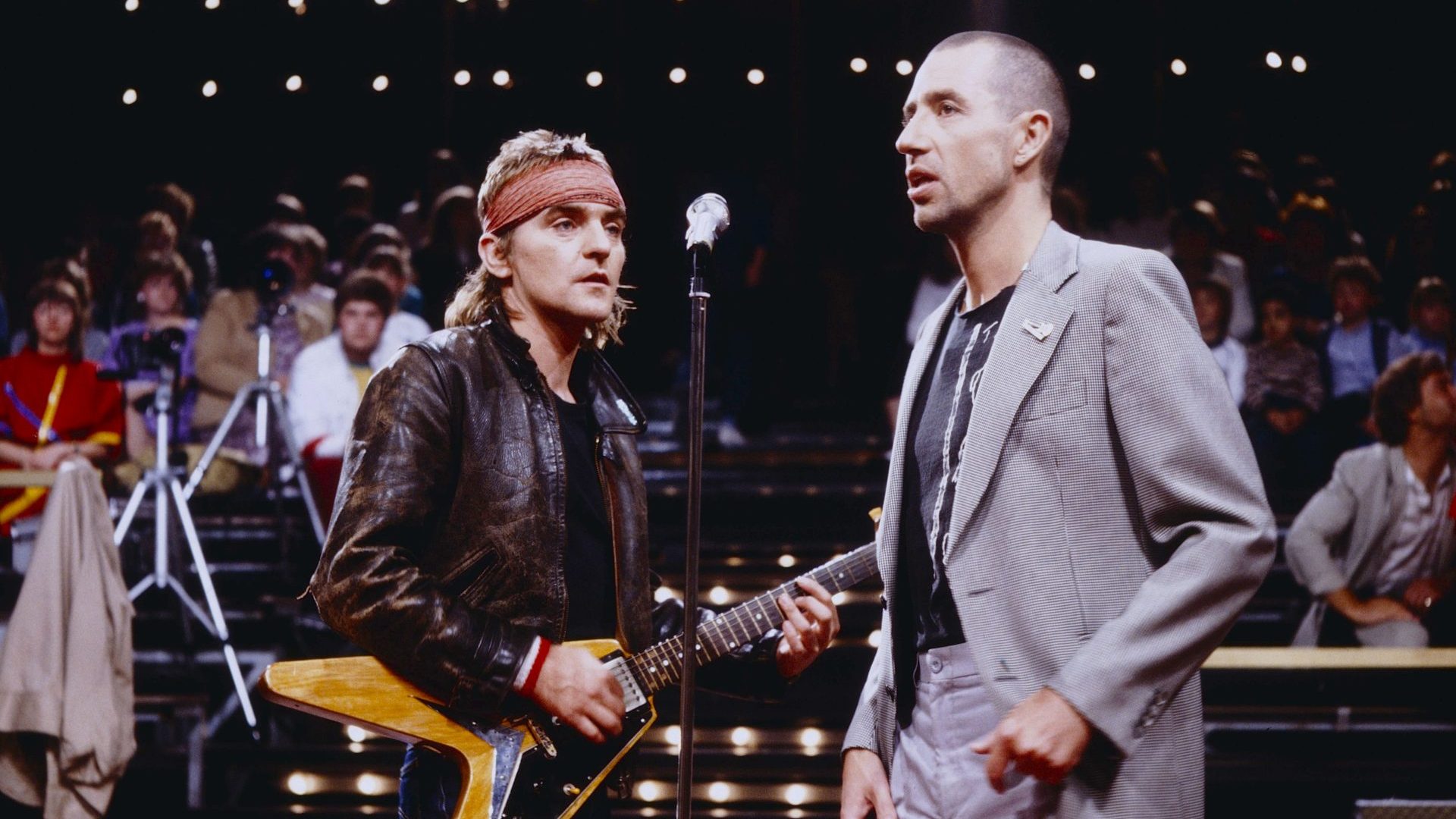

It was guitarist Kralle Krawinkel who put the Dada into Da Da Da, coming up with the catchy, lo-fi, endlessly repetitive keyboard melodies while vocalist Stephan Remmler half-mumbled the faintly nihilist lyrics, “ich lieb’ dich nicht du liebst mich nicht”, “I don’t love you, you don’t love me”.

Trio’s pared-down style was a reaction to the sumptuous and expensive production that had fuelled German electronic music over the previous decade by the likes of Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk, but there was nothing sneering in their output. They were making music, not making a point.

While Trio were associated with the German new wave known as Neue Deutsche Welle along with bands such as Nena of 99 Red Balloons fame, the three-piece described themselves as peddling Neue Deutsche Fröhlichkeit, or New German Cheeriness: while most West German bands concerned themselves with the cold war and nuclear annihilation, positioned as they were right on the faultline of the conflict, Trio set about producing stripped-down songs about the joys of not being in love.

This approach proved creatively freeing rather than restricting; there were three band members so they called themselves Trio. Their debut album was called simply Trio, their second and final studio album Bye Bye. Their music was free of self-indulgence and ornamentation, with most material written to a basic three-chord structure. There was a playfulness about Trio, their live set often featuring a tailor’s mannequin as a backing singer while Krawinkel mimed on toy instruments to the sound of Remmler’s little pre-programmed Casio keyboard.

Yet if anyone was the driving musical force of Trio it was Krawinkel. He described himself as the “heart” of Trio, Remmler as the “head” and, with a characteristic wink, drummer Peter Behrens as the “arsehole”, but he was the creative hub of the band’s output and philosophy.

Krawinkel had emerged into the vibrant live music scene of Germany’s northern port cities during the 1960s. The son of a sea captain from Wilhelmshaven, he grew up in Cuxhaven, on the Baltic Sea coast, cutting his musical teeth in his mid-teens as lead guitarist for The Vampyrs. Towards the end of the decade he played with Just Us, his first collaboration with Remmler, honing his trade with long sets deep into the night for tough audiences of hard-drinking seamen in the clubs and dive bars strung along the coast.

At the turn of the 1970s Krawinkel formed a folk-rock band, the phonetically eponymous Cravinkel, relocated to Hamburg – then the centre of the German recording industry – and signed a lucrative deal with Phonogram Records. After two moderately successful albums and having opened the notoriously disastrous 1970 Love-and-Peace Festival on the Baltic island of Fehmarn, billed as Europe’s answer to Woodstock, the band split in 1972 following a house fire that destroyed all their equipment and belongings.

Disillusioned by the Cravinkel experience, Krawinkel turned to teaching, lecturing at the University of Oldenburg, but keeping his hand in by playing occasionally with a country band called the Emsland Hillbillies.

In 1979 he reunited with Remmler and recruited Behrens to form Trio, who met with low-key success in Germany until Da Da Da propelled them to international stardom.

Perhaps inevitably, the pressure of such astounding success on three lads who just liked making music took its toll. The band split in 1986 after making and starring in a disastrous 1985 feature film, Drei Gegen Drei, in which three generals from a South American military republic, played by Trio, hire doppelgangers whom they intend to have assassinated so they can live new secret lives funded by stolen riches from their national treasury. The film was a financial disaster and confirmed the end of the band.

Remmler and Behrens moved out of the house the three musicians shared, leaving Krawinkel to dabble in solo recordings that culminated in the well-received 1993 album Kralle, but his interests began straying from music and the north German coast he loved.

In the early 1990s, Krawinkel relocated to Seville where he started an olive farm and took up riding horses, occasionally returning to Hamburg to play in pick-up bands in the bars and clubs where it all began. On one occasion, in 1996, he earned a place in the Guinness Book of Records by riding a horse from Seville to Hamburg, at the time the longest continuous ride ever recorded.

Krawinkel was an extraordinary guitar player, as good as Keith Richards they said, only with better technique. Occasionally during Trio concerts he would, for comic effect, embark on flashy guitar solos so long that Remmler and Behrens would start playing table tennis on stage.

Yet this was pure stagecraft, because Krawinkel was never entirely comfortable in the limelight. Despite being the band’s musical driving force, he was more than happy for Remmler to be the face of Trio, remaining in the background as much as he could – the band’s worldwide smash hit, for which he wrote the music, featured barely any guitar, and during those extended live guitar solos he wore a large woolly hat that all but hid his face.

Happily married and financially secure thanks to Da Da Da, Krawinkel’s only vice was the cigarettes he had chain-smoked since his teens, leading to a lung cancer diagnosis in the autumn of 2013 that would kill him within months. He spent his final days back on the north German coast, gazing out at the horizon that had helped to forge his musical dreams.

“The good North Sea air should always be the final part of cancer treatment,” his widow, Monika, told Bild. “Kralle had a kind of holiday at home.”