On April 19, those of a certain persuasion will mark Bicycle Day in a manner that has nothing to do with lycra. It will be the 80th anniversary of the first intentional LSD trip, taken by a 37-year-old Swiss chemist who then cycled home through Basel – private cars were banned from the streets because of the war – while experiencing sensations that were both disturbing and exhilarating.

“I sank into a not unpleasant, intoxicated-like condition characterised by an extremely stimulated imagination. I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic colours. Everything I saw was distorted as in a warped mirror,” Albert Hoffman later reported. Twenty-four years ahead of schedule, he had invented the Summer of Love, with its “cellophane flowers of yellow and green” and “plasticine porters with looking-glass ties”.

Hofmann had been working in the pharmaceuticals department of Sandoz Laboratories since 1929. Now a subsidiary of Novartis, the company’s earlier successes included the analgesic anti-inflammatory antipyrin, a forerunner of ibuprofen (1895), and the sugar substitute saccharin (1899). In 1918, it developed ergotamine, still used today as a migraine medicine, from ergot, a fungus that develops on rye. Hoffman had been continuing the company’s work with ergot when, in November 1938, he synthesised the chemical lysergic acid diethylamide and promptly set it aside for another five years before an accidental ingestion on April 16, 1943 produced interesting results and led to a full experiment three days later.

According to James Kingsland, author of Am I Dreaming? The New Science of Consciousness, and How Altered States Reboot the Brain, Hoffman was the “ultimate geek… He was an academic, meticulous and curious but also bold enough to try out LSD on himself. He was also extremely well-read, a lover of the natural world and very spiritual, and he saw LSD through that lens.”

Yet the original Bicycle Day also revealed the darker side of his creation. As well as vibrant hallucinations, at one point Hoffman was “seized by the dreadful fear of going insane. I was taken to another world, another place, another time. My body was without sensation, lifeless, strange. I then perceived clearly, as an outside observer, the complete tragedy of my situation.”

Hofmann was terrified by these side-effects, but convinced LSD might find a genuine use in neurology or psychiatry. It became a lifetime’s quest. He would eventually become director of Sandoz’s natural products department, giving him free rein to study LSD and other hallucinogenic substances. This led to the synthesis of psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, which produces similar effects to LSD and is, according to Kingsland, “probably the safest psychoactive drug known to science”.

Meanwhile, Sandoz offered free samples, under the trade name Delysid, to international institutions in order to find medical uses for LSD. From the late 1940s until the end of the 1960s researchers attempted to discover treatments for anything from alcoholism – studies backed by Bill Wilson founder of Alcoholics Anonymous – to anxiety, depression and personality disorders.

Luminaries in the field included US psychoanalyst Sidney Cohen, the aforementioned Leary and, in the UK, psychiatrist Ronald A. Sandison. Because LSD-induced effects were judged to be similar to some psychoses, they hoped to discover treatments for these conditions too. “A lot of early research explored LSD as a treatment for alcohol addiction,” says Kingsland. “At the same time, psychoanalysts discovered that low doses helped their patients open up during sessions – like throwing open a window into their subconscious.”

Between 1950 and 1965, 1000 academic papers were published on its potential uses and any number of books emerged from authors whose credentials varied between academic and pop science. Results were sporadic but occasionally showed promise.

Yet LSD’s astonishing effects – including feelings of distorted time, hallucinations, intense emotions, confusion and altered states of thinking – had brought it to the attention of the wider public. Aldous Huxley, British author of dystopian fiction, was a staunch proponent believing it could make humanity a more peaceful species, and while he took the drug and his use of it seriously, it’s arguable he helped to glamorise its recreational use, although Amanda Feilding, director of the Beckley Foundation which promotes scientific research into psychoactive substances and global drug policy, disagrees. “On the contrary, Huxley and other thinkers like Ernst Jünger were precise and measured in their thoughts about psychedelics, both in terms of risks and benefits,” she says.

By the mid-1950s, reported users included Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, based on his experiences as part of a CIA LSD trial. Kesey even hired a bus to tour the US extolling the virtues of psychedelics. The likes of gonzo-journalist Hunter S. Thompson and poet Allen Ginsberg became aficionados. As the concept of alternative lifestyles, fashion and music in defiance of mainstream society grew, so did associated drug use.

The year after Leary and a second Harvard psychologist Richard Alpert were dismissed in 1963 for administering LSD on themselves, they and Ralph Metzner published The Psychedelic Experience: A manual based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead. They claimed LSD had the power to radically change society and should be available to all. Although Leary is often credited as the man who almost single-handedly invented 1960s counterculture, he became the subject of FBI raids, spent time in exile and in prison, and was described by US president Richard Nixon as “the most dangerous man in America”. Says Kingsland: “At that point the writing for LSD was on the wall. Leary’s slightly crazed proselytising had a largely negative effect.”

Feilding agrees. “Once LSD became associated with the anti-Vietnam war movement and other groups the government found troublesome, the regulators were determined to ignore the scientific evidence.”

Beatles John Lennon and George Harrison were dosed by their dentist in early 1965, and while the full fruits of their acid experimentations would not surface until Revolver a year later – with its concluding track Tomorrow Never Knows borrowing from Leary – some theorise that it even inspired the lines “Now I find I’ve changed my mind, And opened up the doors” in Help.

Also answering Leary’s call were rock stars from the Grateful Dead to Jimi Hendrix, and any number of writers, artists and actors from Tom Wolfe to H. R. Giger to Peter Fonda – whose tripping scene in the movie Easy Rider attracted much opprobrium . Yet while they embraced LSD as a life-affirming wonder drug, governments had the opposite reaction.

“LSD gained an ingrained reputation as a party drug, which made it more difficult for scientists wanting to do serious research,” says Kingsland. Prohibition was the result. “Most of the stories surrounding LSD were exaggerated or unfounded,” says Feilding. “But moral panic was the outcome.”

And while Leary was correct to point out that LSD isn’t addictive in itself, users can become addicted to their experiences causing lasting psychological trauma. Lawmakers made much of its connections, actual or anecdotal, with changes in mood, panic attacks, psychosis, suicidal thoughts, high blood pressure, anxiety and flashbacks.

By the late 1960s it had been outlawed in most western nations. Even the CIA’s MK-Ultra programme to identify drugs that could be used in interrogations, often using unwitting subjects, was canned on the grounds of illegality and cost.

LSD’s advocates and academic researchers pretty much lay the blame for its prohibition and subsequent suppression of serious research at Leary’s feet. Sandoz ceased production in 1965 while Hofmann himself was dismayed that a drug with genuine medical potential was being used recklessly.

LSD’s stock was at its lowest. Urban legends abounded, from stories of people on LSD going blind while staring too long at the sun, or falling to their deaths while convinced they could fly off the nearest high building. Then there was the character alleged to have taken so much acid that he permanently believed himself to be a glass of orange juice and so daren’t lean over in case he spilled.

Many of these stories were wildly exaggerated, but there were enough high-profile casualties – Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett and the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson among them – to make this the drug’s low watermark. Aside from a brief period when illegally produced LSD and MDMA – or ecstasy – led to the Acid House scene and Rave subcultures in the late 1980s and early 1990s, its heyday seemed past.

But more recently, there has been a revival in academic research, and an associated, but separate resurgence in usage. In 2012 a study into LSD’s ameliorating effects on alcohol addiction again showed promise, while in 2014 Swiss psychiatrist Peter Gasser reported in The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease that LSD had demonstrable benefits in treating anxiety. It was the first study in 40 years to assess the therapeutic effects of LSD. Other recent clinical trials have studied LSD’s use in treating migraine, depression and declining brain plasticity.

And in 2015 it was reported that young professionals in San Francisco were microdosing LSD – taking perhaps 10 per cent of the amount normally required to induce psychoactive effects – thus enabling them to become “more innovative”. Anecdotal evidence suggested enhanced creativity, attention and energy levels. However, researchers have yet to establish these benefits in controlled conditions.

“LSD’s problem as a therapeutic is that its effects can last eight hours or more, which makes it impractical,” says Kingsland. “As far as microdosing is concerned the results have been mostly indistinguishable from placebo. But you’d need modern clinical trials to assess this properly, and they simply haven’t been done.”

Governments, however, seem unmoved. A spokesperson at the Home Office said Britain currently has no plans to decriminalise LSD while the US National Institutes of Health says: “LSD is a potentially harmful substance, leading to dangerous consequences including altered perception, a lack of inhibition and psychoses, with potentially damaging and permanent effects.” And as Kingsland adds: “The drawback is that all psychedelic drugs can cause a manic episode or unmask an undiagnosed psychosis. The risk is particularly high for people with bipolar or schizophrenia, or a family history of these. Until this risk has been thoroughly investigated, this remains a limitation on their clinical use.”

LSD remains illegal throughout the world, although it has been decriminalised in Portugal and the Czech Republic. Whether it has a future as a mainstream therapeutic drug probably depends on governments, not scientists. “Use of illegal drugs goes up every year, regardless of how much money is spent fighting it,” says Feilding. “Consumption cannot be eradicated, a situation increasingly recognised by health and regulatory professionals. The best we can do is implement policies of harm reduction. This also makes possible the exploration of these compounds for potential medical and psychological benefits.”

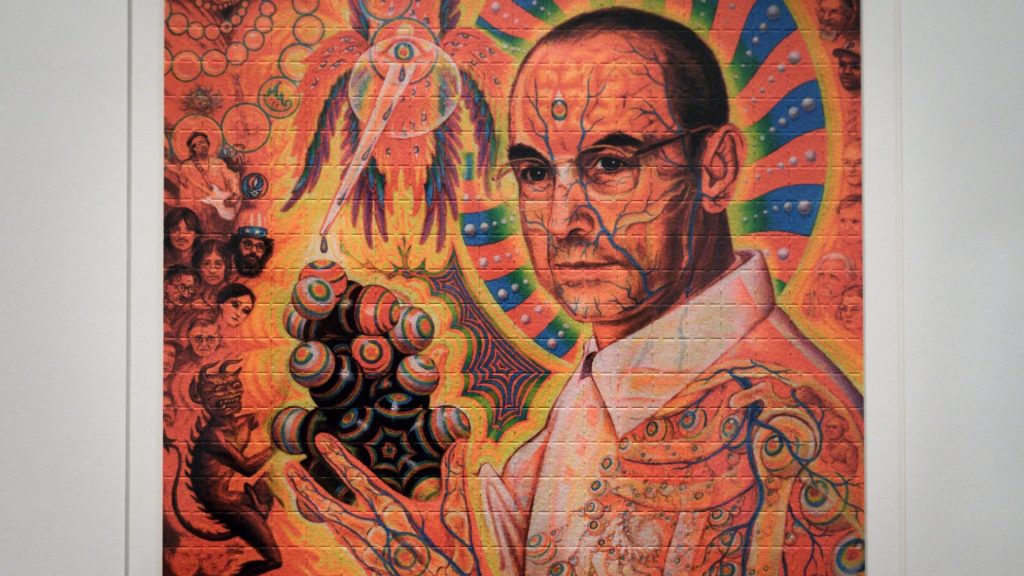

Hofmann died in 2008 aged 102. On his 100th birthday, Feilding had written: “If it was not he who discovered LSD, but rather LSD that found him, then indeed it chose wisely. As those who know him are aware, they are a very well-matched pair.

“It is a rare thing in the modern world, or in any world, for a man to live beyond a century. But to live so long with senses so intact and above all with his luminous intellect undimmed, is so exceptional as to suggest a strikingly remarkable individual. He takes pride in the collage, made by an admirer, juxtaposing portraits of Newton, Einstein and Hofmann, three men who have fundamentally transformed the way we conceive reality. Apart from his scientific achievements, it is his personal qualities – nobility, humanity and breadth of vision, – that mark him out as an outstanding natural philosopher.”

Hoffman, meanwhile, had continued to take small doses of LSD throughout his life. Describing it as a “sacred drug” he wrote in his memoir LSD: My Problem Child: “I believe if people would learn to use LSD’s vision-inducing capability more wisely, under suitable conditions, in medical practice and in conjunction with meditation, then in the future this problem child could become a wonder child.”

Eighty years later, as we’re still struggling to come to terms with his discovery, perhaps it might be worth our while to pay attention.