The two most remote native-English speaking communities on earth are to be found in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, on the island of Tristan da Cunha, which lies 1,505 nautical miles (2,787km) from the South African coast; and in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, on Palmerston Island in the Cook Islands, which is 430 nautical miles (800km) from Rarotonga, the main island of the Cooks.

Neither island has an airfield, the only way in and out being by sea.

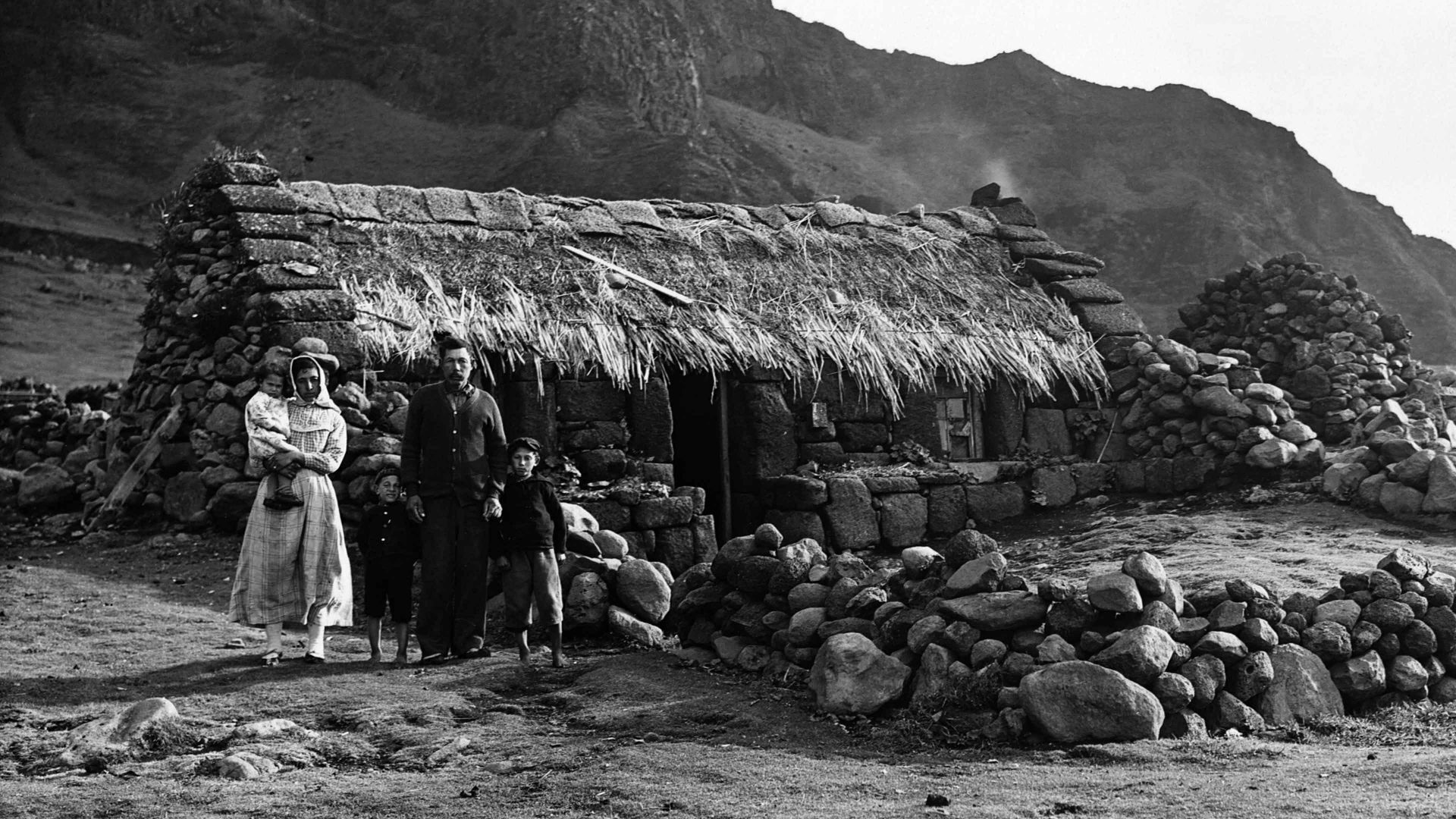

Tristan is a South Atlantic British dependent territory which is said to be the most remote permanently inhabited settlement in the world, the nearest habitation being St Helena, which is about 1,500 miles (2,400km) away. A British garrison was stationed on Tristan in 1816 to prevent it being used as a base to rescue Napoleon from St Helena, and the islands were formally annexed to Britain. When the garrison left in 1817, three soldiers asked to stay; during the rest of the 1800s they were joined by shipwrecked sailors, a few European settlers, and six women from St Helena. By 1886 the population was 97; today it is about 250.

Palmerston Island is one of a number of sandy Pacific Ocean islets on a continuous ring of coral reef enclosing a lagoon. There is no safe entry for large ships. When Palmerston was visited by Captain James Cook in June 1774, it was uninhabited, though some ancient remains have been discovered.

The Palmerston community has a rather astonishing history, and the story of how the islet came to be the home of a community of mother-tongue English speakers is a strange and fascinating one. The community dates from the middle of the 19th century. All the islanders are descended from a single Englishman, William Masters (also spelt Marsters), a ship’s cooper and carpenter who arrived in July 1863.

The linguist Rachel Hendery has written a book about the community with the clever title of One Man is an Island. According to Hendery, it is not entirely clear why Masters ended up in Palmerston, nor where in England he came from: the historical records show that Leicestershire in the English Midlands, Gloucestershire in the west of England, Yarmouth in Norfolk, and Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast, are all possibilities. She reports that he left England for the US goldmines, and then spent some time in and around the Pacific before ending up on Palmerston.

Among the original group of people who arrived with William Masters were three Polynesian women – Akakaingara, Tepou Tinioi and Matavia – all from the island of Tongareva (also known as Penrhyn). Akakaingara and Tepou Tinioi were his wives. Matavia married him after her first husband, who she had had a son with, died, and Masters adopted the boy.

Masters in the end fathered 17 children of his own, and the vast majority of the 60-odd islanders today are his descendants. He insisted that they should all speak English, which they naturally had to learn from him.

Their descendants, who have lived on the island in relative isolation ever since, still speak it as their native language today, in a form somewhat influenced by the Polynesian language Tongarevan.

PENRHYN

Penrhyn means “peninsula” in Welsh, so is a rather strange name for a Polynesian island. The Lady Penrhyn was one of the ships which was part of the First Fleet carrying convicts from England to Australia. On its return voyage it sailed past Tongareva, bestowing its name on the place. Appallingly, Penrhyn was depopulated by Peruvian slavers in 1864.