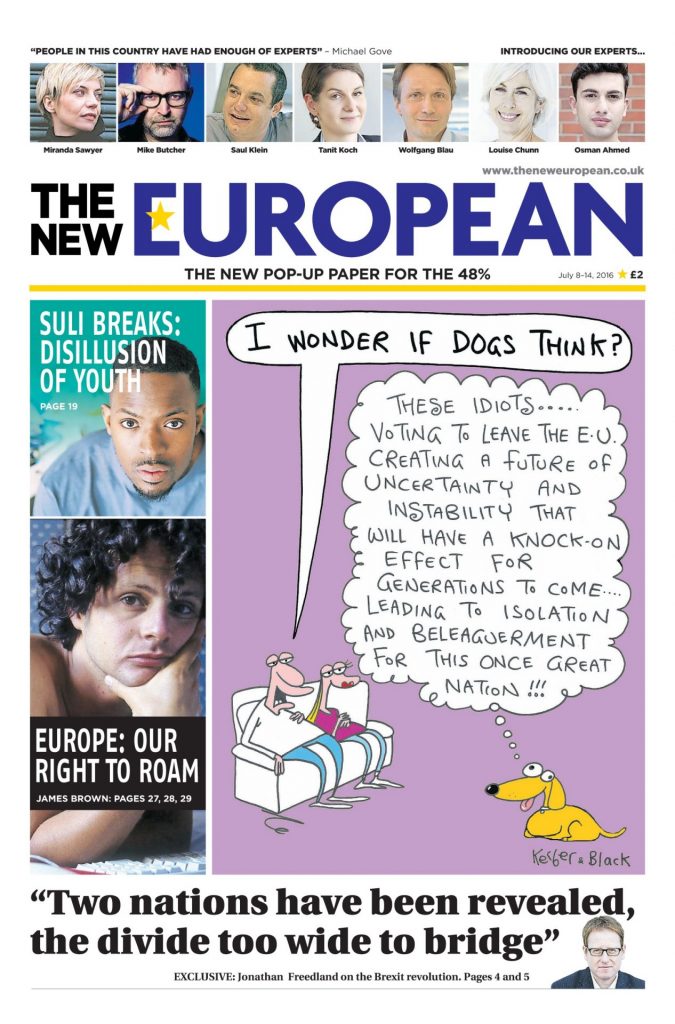

In a plastic folder in my study, I have three copies of the first-ever edition of the New European. Not quite hermetically sealed, but kept from direct sunlight to avoid what the book trade calls foxing or fading. As historical documents go, they may not be the Gettysburg Address or the handwritten lyrics to Yesterday, but I did once see a copy for sale on eBay for fifteen quid.

On page three of that first edition is a leader column I can’t recall writing (we launched in 10 days, so it’s all a bit of a blur), but on re-reading it didn’t make me cringe quite as much as I feared.

This was, remember, just a week after the referendum:

“The fact that Leave politicians are so openly clueless about what to do now the vote is won only adds to the sense that this is a self-inflicted wound of elephant gun proportions. Add to that the chronic, oppressive admonitions to the 48% on social media and at the bus stop and the cafeteria and the pub bar to shut up, quit whining, move on and just accept we lost.”

That sense of dismay, Leave’s cluelessness and the insistence that Remain should shut up lasted another solid nine years. When Keir Starmer stood up alongside António Costa and Ursula von der Leyen to announce their common reset of UK/EU relations, it felt as if we’d turned a corner. Not a screeching U-turn, not even a hard left at the crossroads. Maybe it was just the mildest of doglegs. But a corner all the same, with a trajectory heading away from the cliff edge of perpetual delusion.

Finally, after David Cameron, after Theresa May, after Boris Johnson, after Liz Truss, after Rishi Sunak and – significant to the shaky thesis of this article – after Starmer himself, here was a British prime minister not actively gaslighting the British public about the potential for Brexit to work.

That’s a positive. Ed Davey is absolutely right – it’s nowhere near enough. But at this moment in history, let’s take the win, imperfect as it is, and encourage further good behaviour.

To date, there’s been little by way of encouragement. Starmer’s first anniversary as PM is roughly five weeks away. He has been a monumental disappointment.

Central to that disappointment is this question: what does the prime minister actually stand for? To quote the British-American motivational speaker Simon Sinek: “People don’t buy what you do. They buy why you do it.” What is Starmer’s why?

Only around one in five of us has a favourable opinion of Sir Keir Starmer. For context, that 22% popularity polling makes him six points less popular than Sir Tony Blair is today. Yes… it’s really that bad.

The public’s brutal assessment is more than a verdict on policy – as misjudged as those policies have been to date, especially the winter fuel allowance debacle – or No 10’s cack-handed public communications.

It’s a verdict on him as a leader, as a man. People are unimpressed not just with his government, but with him. The absence of audacity and vision. The predilection for meaningless baloney in place of hard truths.

You don’t have to be James “The economy, stupid” Carville to wince when you hear “national renewal”, “fixing the foundations”, “planning for change” and – most gratingly of all – “taking back control”. Seriously, which eejit wrote that singularly triggering mantra into his speech, and is he still gainfully employed?

The latest catchphrase – “acting in the national interest” – is as bad. My daughter, a politics A-level student, actually laughed out loud when she heard him say that on the radio. “I should hope so,” she said. “Isn’t that his bloody job?”

Worse than the meaningless platitudes, though, is his ill-advised tactic of taking the fight to Nigel Farage on the Reform leader’s home turf. All this “island of strangers” nonsense and “smash the gangs” fantasies are water pistols to a knife fight. If you want to see where that strategy leads, take the train to Runcorn.

So if Starmer has no discernible why, what chance he will discover a why for Britain’s future?

Nietzsche – almost as unpopular a reference point these days as Enoch Powell – understood the motivation a good why can give. Hat man sein Warum des Lebens, so verträgt man sich fast mit jedem Wie. “He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.”

The converse is equally true: those with no sense of purpose will find any burden intolerable.

Here is the case Starmer the lawyer needs to win – not like some conveyancing solicitor arguing the toss over a party wall, but like a great prosecuting barrister, alloying policy with poetry, persuading a doubtful jury with the sheer weight of his argument. The jury, of course, being us.

The Tories have already self-interred. Farage is the man with momentum. The problem facing Farage in this new world is that he is a man deeply mired in the past.

Mr Ukip, Mr Brexit, Mr Breaking Point poster, Mr Trump’s lickspittle. This is how you characterise a man like Farage if you want to challenge him at the ballot box. Not by impersonating him on his specialist subject – The Past.

Here is the stark choice Starmer must put in front of voters: a toss-up between Farage’s view of the past, and Labour’s view of the future.

Mission impossible? Perhaps. Starmer governs at a unique period in history. It’s impossible to listen to the radio news for half an hour without hearing the phrase “new world”. It is indeed a new world we find ourselves in. And a new world requires a break with the past. It demands new thinking, new strategies.

It is, I suppose, a choice we’ve all got to make now. Do we continue to litigate the past, or do we make a break and vigorously prosecute our case for the future?

I know which I find the most interesting prospect. You?

Matt Kelly is the founder and editor-in-chief of the New European