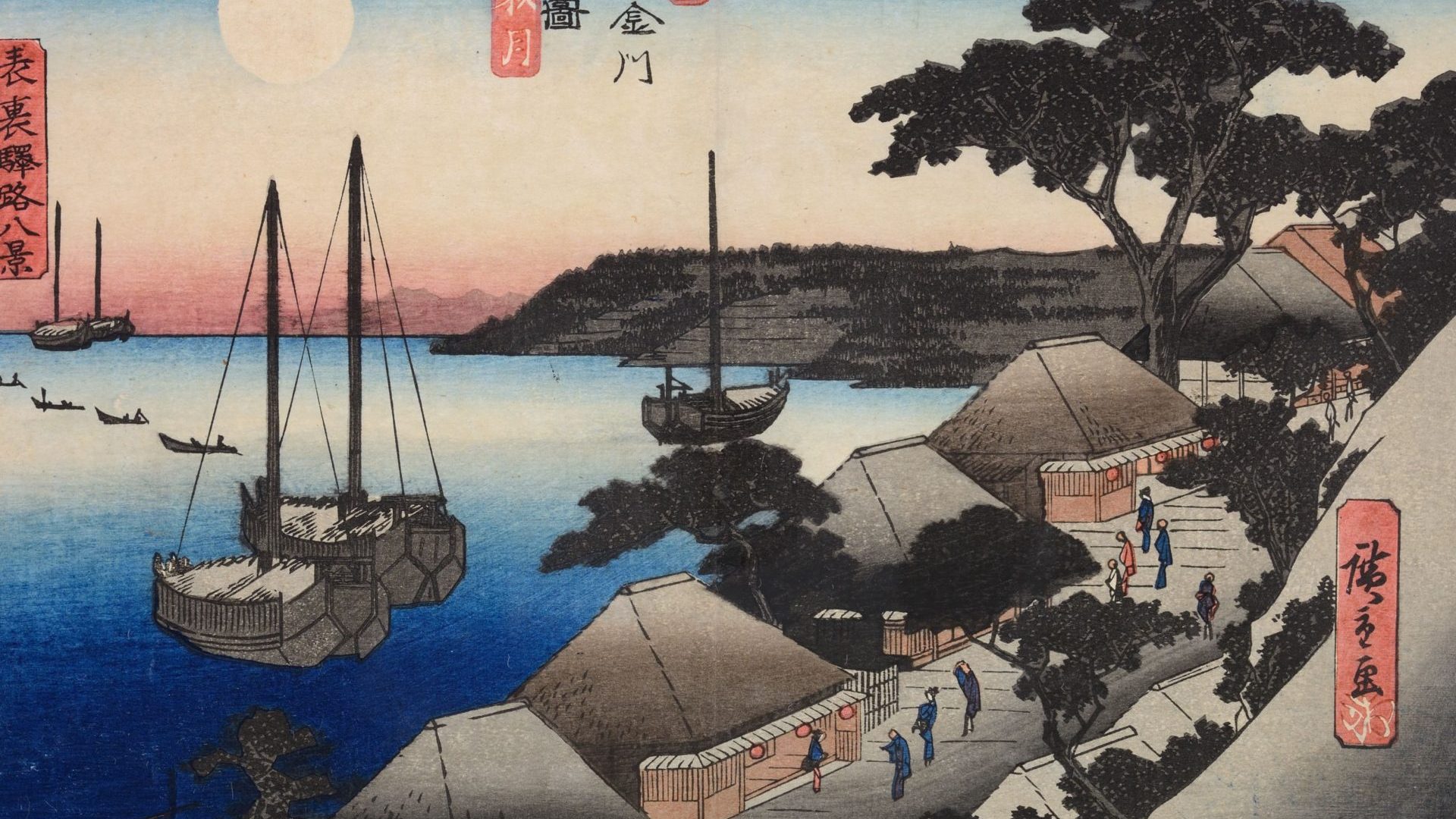

Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road

(British Museum, until 7 September)

Devotees of Kazuo Ishiguro’s early masterpiece, An Artist of the Floating World (1986), will be familiar with the Japanese ukiyo-e figurative tradition: the depiction of the everyday life of merchants, warriors, kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, and courtesans.

One of its later and most revered masters – rivalled only, perhaps, by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) – was Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), whose work is celebrated in this stunning exhibition (the first London show dedicated to his prolific creativity in more than 25 years).

Born Andō Tokutarō, the son of a samurai in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), in the era of the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867), Hiroshige established himself with a series of remarkable prints of the Tokaido, the 310-mile-long eastern coastal highway that connected his birthplace with the imperial capital of Kyoto.

His work is marked by a love of the natural world, the Buddhist serenity of landscape, the beauty of the skyline. But look closer and you see that his greatest affection was reserved for the day-to-day encounters, predicaments and pleasures of the people he witnessed.

So here is Cherry Blossoms on a Moonless Night Along the Sumida River (1847-8), a colour-woodblock print triptych, that depicts three women strolling along the embankment under the silhouette of a flowering tree. One of them carries a lantern, inscribed with the name ‘Ogura-an’, a famous restaurant near Mimeguri shrine. In her other hand is a basket full of souvenirs bought by the other two. The detail is exquisite.

Or Scene at an Inn on Mt Kanō, Kazusa Province (1840s-1850s), from a woodblock-printed illustrated book, which portrays six poets gossiping and tucking into a bowl of snacks, after an evening bath, as the rain pours down outside their lodgings. Their robes suggest that they are from merchant families.

Or The Exit Willow at Shimabara (1834), a scene from Kyoto’s red-light district as dawn rises, in which a drunken punter is steadied by servants as he heads home and young women look on with amusement.

The juxtaposition of cosmic order and human foible is beautifully rendered. Small wonder that Hiroshige made such an impact upon western artists – especially Van Gogh, who collected his prints and meticulously traced The Plum Garden at Kameido (1857). Whistler, Toulouse-Lautrec, Hockney and, more recently, Julian Opie have all been influenced by him.

Few exhibitions are truly unmissable, but this is among them.

The Four Seasons

(Netflix)

The return of the mighty Tina Fey to a leading televisual role is cause enough for celebration. It is 12 years since 30 Rock ended and – aside from an hour-long special of that show in 2020 and occasional cameo roles, notably in the excellent Only Murders in the Building – she has been sadly absent from the small screen.

In this eight-episode comic drama, she and fellow 30 Rock writers, Tracey Wigfield and Lang Fisher have updated Alan Alda’s classic 1981 movie about three couples who have known each other for decades and take holidays together (the title is, of course, inspired by Vivaldi’s violin concerti, which act as soundtrack to movie and series alike).

Fey is Kate (played by Carol Burnet in the original), married to Jack (Alda’s character, now played by Will Forte); Len Cariou as Nick and Sandy Dennis as Anne are replaced, respectively, by Steve Carrell and Kerri Kenney-Silver; Danny (Jack Weston) and Claudia (Rita Moreno) become Danny (Colman Domingo) and Claude (Marco Calvani). As a mark of his endorsement, Alda, now 89, has a bit part at a crucial moment in the plot.

Out of the blue, Nick reveals that he is leaving his wife: “It’s Anne. I hate her. No, I don’t – I don’t. She’s a kind woman. She’s just – given up. She doesn’t do anything… We’re like co-workers at a nuclear facility”. This apparent act of recklessness triggers a chain reaction of doubt, regret and recrimination within the group, as old assumptions are tested and familiar friendships subjected to fresh scrutiny.

Danny, in denial about his own heart condition, says to Jack: “How can you be even less chill in your fifties than you were in your twenties?” When Nick begins a relationship with a younger woman, Kate teases him to the point of reproachfulness: “It’s weird that your girlfriend wasn’t born when Reagan got shot”.

He, in turn, struggles with the fluidity of the modern dating scene: “Why doesn’t anybody like labels anymore? I like labels. I love them. I miss the 90s when it was just ‘girlfriend’ or ‘friend zone’”.

This is old-fashioned comedy in the best sense, a precisely measured cocktail of innocence and cynicism. In spirit, it predates the modern romcom, the blockbuster genre founded by the Big Three: When Harry Met Sally (1989), Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and You’ve Got Mail (1998). Instead, The Four Seasons explores the prairies of middle age, suddenly shaken by tremors of unwelcome change, and extracts much sharp wit and gentle pathos from its timeless themes.

Thunderbolts*

(General release)

It is one of the most familiar conceits in movies: a group of misfits, outsiders or outright villains is convened to enact a plan that is at least notionally on the side of the angels. Take, for example, Seven Samurai (1954), The Dirty Dozen (1967), and The Expendables franchise (2010-23); and there’s an entire subgenre in the superhero world, from Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy trilogy (2014-23) to DC’s two Suicide Squad movies (2016 and 2021).

In this case, the reluctant heroes are Russian-born assassin Yelena Belova (Florence Pugh), sister of the late Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson); her down-on-his-luck father Alexei (David Harbour), formerly Red Guardian but now driving a limo; John Walker (Wyatt Russell), the disgraced second Captain America; Ghost (Hannah John-Kamen); and, Bucky Barnes (Sebastian Stan), formerly the Winter Soldier and now a congressman.

After the villainously camp CIA director Valentina Allegra de Fontaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) sends Yelena, Walker and Ghost on apparently separate clean-the-scene missions – in practice, to kill one another – they team up with Alexei and Bucky to find out what she’s up to.

Valentina’s secret scheme involves a medical test subject known only as Bob (Lewis Pullman). He is diffident, disoriented and wearing hospital scrubs: all sure signs in superhero movies that he probably has world-destroying powers, too. The Avengers are no more (for now): so who will step up to the plate?

The 36th Marvel Cinematic Universe movie is amusing popcorn fare that also makes a more serious effort to address mental health issues. “There’s something wrong with me,” says Yelena, as she prepares to parachute off a skyscraper (it is no coincidence that the force of evil in the movie is called the Void). In this respect, she connects with Bob, a traumatised figure with a wretched backstory.

Thunderbolts* also establishes Pugh as a fully-fledged screen star who can carry a blockbuster release by herself. And yes, the irritating asterisk after the movie’s title is explained. Next up, in July, The Fantastic Four: First Steps.

The Handmaid’s Tale

(Channel 4)

I have written a longer piece for TNE on Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel, the fantastic television series it inspired and their importance as a guide to contemporary authoritarianism, especially Donald Trump’s MAGA movement.

So this is just a reminder that the sixth and final season is back on Channel 4, which is also streaming the preceding five seasons. The first episode begins where season five ended: with former handmaid, June Osborne (Elisabeth Moss), meeting Serena Waterford (Yvonne Strahovski) on a train to Alaska.

For now, at least, Serena claims to have turned against the patriarchal tyranny of Gilead and seeks to make an ally of the woman she once regarded as an enslaved member of her household. “The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” she suggests. “On a case-by-case basis,” is June’s reply.

I won’t spoil what follows – except to say that I have seen eight of the final ten episodes, and they are quite something.

Notes to John by Joan Didion

(4th Estate)

The republic of letters loves few things more than secondary issues: questions or dilemmas that lurk at the fringes of a text but often generate a vivid controversy. This is especially so when it comes to the posthumous publication of work by famous authors.

Mostly, these fierce public arguments lead nowhere, precisely because they are generally unanswerable. We can all, presumably, be grateful that Max Brod ignored Franz Kafka’s express wish that his entire body of work be burned. Virgil wanted the Aeneid to be destroyed after his death – which, all things considered, would have been a shame.

I am not sure how much the world gained by the publication of Vladimir Nabokov’s The Original of Laura (2009). But I’m glad that David Foster Wallace’s incomplete final novel The Pale King (2011) made it into print and that the sons of Gabriel García Márquez committed what they themselves admitted was “an act of betrayal” in publishing his gem of a novella, Until August (2024).

Joan Didion did not explicitly authorise the release of these notes of her exchanges with the New York psychiatrist Roger MacKinnon between December 1999 and January 2002, addressed to her husband John Gregory Dunne. But the documents in question are also available in the New York Public Library as part of the couple’s archive, with no restrictions upon access.

Much more interesting is the content itself: rigorous, unflinching accounts of MacKinnon’s undoubtedly impressive efforts to tease out of Didion what was wrong with her relationship with her adopted daughter, Quintana Roo. Under treatment by another psychiatrist for borderline personality disorder, depression, and alcoholism, Quintana posed a painful challenge to Didion, not only as a mother but also as a writer: she didn’t seem to be able to write her way out of the problem. Which, in her eyes, was close enough to an existential crisis.

“You can only love her,” MacKinnon told her. “You can’t save her”. But, just as Quintana self-medicated to make herself feel (temporarily) better, so Didion scurried back to her desk in an effort to tame reality. As her psychiatrist said: “you control the situation through your work and your competency”.

He also identified a deep co-dependency between mother and daughter. “You’re allowing her to hold you prisoner,” he said, “which in turn imprisons her.” He even suggested that Didion and Dunne’s very closeness as a couple might be playing a role in Quintana’s sense of isolation and exclusion.

If you haven’t read any Didion before, don’t start here: instead, get stuck into Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) and The White Album (1979), both classics of the so-called “New Journalism”. All the same, Notes to John essentially turns The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights (2011), her superb two-volume account of bereavement, into a trilogy; and thus indisputably enriches our understanding of one of the great essayists of the past century.