In his 1988 novel Immortality, Milan Kundera described his biggest worry about death.

“No novelist is dearer to me than Robert Musil,” he wrote. “He died one morning while lifting weights. When I lift them myself, I keep anxiously checking my pulse and I am afraid of dropping dead, for to die with a weight in my hand like my revered author would make me an epigone so unbelievable, frenetic and fanatical as immediately to assure me of ridiculous immortality.”

Assured of a posthumous legacy a long way from ridiculous, Kundera died after a long illness on July 11 at the age of 94 – unencumbered by dumbbells. Instead, he will be remembered as one of Europe’s finest and most innovative writers who was largely responsible for defining the European novel in the modern age. In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting and The Unbearable Lightness of Being he produced two of the 20th century’s greatest works of fiction.

Having left his native Czechoslovakia in 1975, Kundera’s death leaves a life divided almost exactly in half between years spent in his home nation and in exile in France. Indeed, Immortality was the last book he wrote in Czech: his later works were all composed in French.

While often cited as a contender, it is frankly scandalous that Kundera was never awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Few modern writers have produced work of his consistently high quality, let alone his contribution to establishing a distinct central European voice to the world of literature.

“I think that the importance of the novel in European culture has been enormous,” he said in 1984. “European man is unthinkable without the novel, he was created by it… Trying to construct someone who isn’t you, it’s an extraordinary way out of your egocentricity, to understand someone who thinks differently than you, and not only to understand him but in a certain sense to defend him against yourself even. And that is very European.”

Nobody wrote like Kundera. His novels were meticulously constructed – nearly all of them are divided into seven sections or chapters – yet adventurous in style, with an idiosyncratic prose rhythm that was unique to him. That rhythm was instilled in Kundera from the beginning.

He was born into a musical household in Brno at the end of the 1920s, his father Ludvik a concert pianist and head of the city’s prestigious music academy. Kundera grew up around music that revolutionised form and technique: Ludvik had studied under Leos Janacek and was an admirer of Bartok, Stravinsky and Schoenberg, composers who dragged classical music into the 20th century by creating exciting new sounds for a new age.

Kundera would do the same for literature, his work thrumming with innovative rhythm and style while exploring the outer realms of his imagination. The tumultuous nature of his fiction also reflected the remarkable times through which he lived. Having spent his adolescence under Nazi occupation, Kundera was an early adopter of communism and joined the Czechoslovak Communist Party in his teens just before it seized power in 1948.

“Communism enthralled me in much the way Stravinsky, Picasso and surrealism had,” he wrote. “It promised a great, miraculous metamorphosis, a totally new and different world.”

He graduated in film studies from the Charles University in Prague and was appointed lecturer in world literature at the school of film there despite having been expelled from the party in 1950 for anti-communist activities. He wrote plays and poetry in a style that eschewed prevailing socialist realism yet still forged an enviable reputation on Prague’s literary scene. While remaining firmly on the fringes of the establishment narrative he was not yet the dissident voice he would later become, receiving high praise for a 1955 propagandic poem that praised a communist hero in a work he later disowned as written while trying to find his true voice.

That voice truly emerged in his 1967 novel The Joke, which established him first as a leading voice in Czech national literature, then when published abroad in a French translation as a writer with an international future.

Loosely based on his own expulsion from the party, the book charts the consequences for a student who writes a quip about Trotsky in order to impress a girl. His first novel it might have been, but The Joke is unmistakable Kundera: split into seven sections, full of sparky humour, containing a strong erotic undercurrent and exploring the absurdities of everyday life in a totalitarian regime.

Yet The Joke would spend less than a year on Czechoslovak shelves before the Prague Spring was crushed by Soviet tanks and a new era of intense repression began. Kundera’s novel was banned and its author found himself blacklisted, fired from his teaching job and for a while scraping a living as a labourer and musician accompanying cabaret shows. He even claimed to have lived in a forest for a time.

By 1975 his reputation outside Czechoslovakia had grown enough to prompt the offer of a guest professorship at the University of Rennes, acceptance of which meant Kundera and his wife Vera joined the steady trickle of intellectuals leaving the country for the west. They intended to return but when their citizenship was revoked in 1979 the couple settled permanently in France and became French nationals two years later.

“When the German intellectuals left their country for America in the 1930s, they were certain they would return one day to Germany and considered their stay abroad temporary,” Kundera said in 1985.

“I, on the other hand, have no hope whatever of returning. My stay in France is final and therefore I am not an emigré, France is my only real homeland now.”

Much of this was reflected in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, published in French and in English in 1979. A characteristic sequence of seven stories, the book ranged across philosophy, history and autobiography to produce a narrative that stunned western critics with its originality, its nailing of totalitarianism and call for resistance to the destruction of culture in the countries of the Soviet bloc.

“Let us not be romantic,” said Kundera. “When oppression is lasting it may destroy a culture completely. Culture needs a public life, the free exchange of ideas; it needs publications, exhibits, debates and open borders.”

In 1984 he bettered even the international success of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting with The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Set in Prague in 1968, the novel explored further the importance of freedom and culture under an oppressive regime through two couples, each struggling with personal and political challenges, and became a huge international bestseller adored universally by critics.

“It is so amazingly better than anything he has written before that the reader can hardly believe it, is continually being lost in astonishment,” was the verdict of the London Review of Books, a sentiment echoed across the western world.

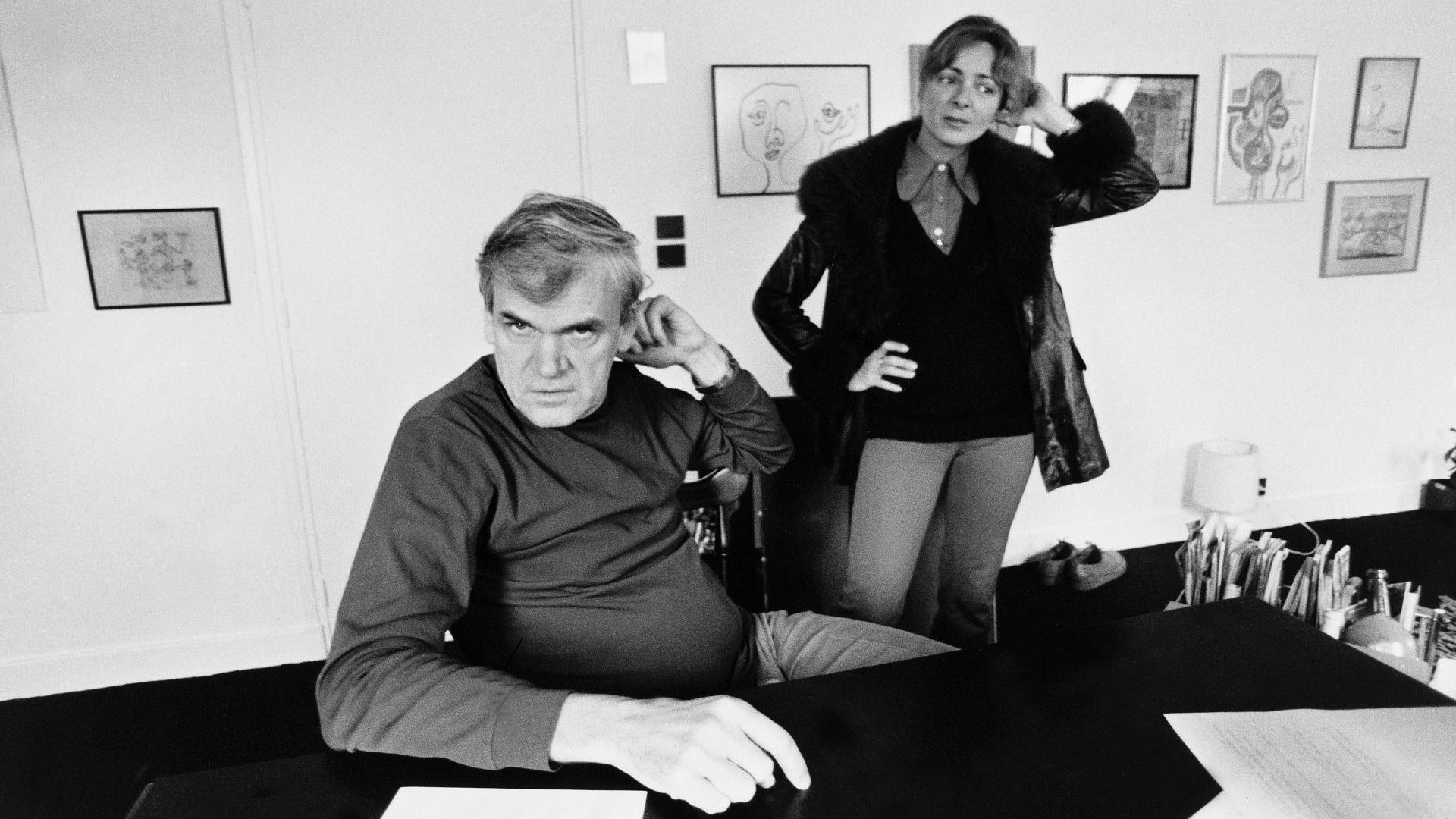

Holed up in his attic flat in Montparnasse, the walls lined with modern Czech art, as his success grew so Kundera withdrew from public view, leaving Vera to deal with the constant interview requests and invitations. He had never exactly relished being interviewed, but such exchanges became increasingly rare.

“An author, once quoted by a journalist, is no longer master of his word,” he said. “And this, of course, is unacceptable.”

In 1980 he had told Philip Roth, a keen Kundera advocate from the beginning who became a close friend, “When I was a little boy in short pants I dreamed about a miraculous ointment that would make me invisible. Then I became an adult, began to write, and wanted to be successful. Now I am successful I would like to have that ointment to make me invisible.”

Although he became a revered voice in a divided Europe, a figurehead of dissidence even if he rejected the term himself, Kundera did have moments where such an ointment would have been useful. He drew persistent criticism for the objectification of his women characters, for example, many of whom suffered violence and humiliation, but most challenging of all, in 2008 claims emerged that, during the 1950s, Kundera had betrayed a Czech airman working for the CIA to the authorities, leading to a long prison sentence – something the author fervently denied.

Whatever the truth of the matter, it was a reminder that many in Prague were still reluctant to forgive those who left rather than, like Václav Havel, stay, resist and attempt to change the country for the better.

“It seems to me that all over the world people nowadays prefer to judge rather than to understand, to answer rather than to ask,” Kundera wrote, going on to criticise “the noisy foolishness of human certainties.”

Aware that uncertainty was the nature of the world, Kundera never stopped asking, never stopped seeking a certainty he knew would always be elusive. Perhaps his displacement lay at the heart of it, having left a regime constructed on the brittleness of sweeping certainties to become an outsider for the rest of his life, finding a home but not being at home, living permanently elsewhere.

“‘Home’ is our national enigma,” he said in 1984. “Czech literature, Czech mythology, is based on a glorification of the house, of the household, of das Heim. Actually, this is true all over central Europe. The same adoration of the household exists in Austria and Hungary and maybe even Germany. You see it with Heidegger. You see it at a very exalted level, of course, but still you see it – this glorification of roots, this idea that life beyond one’s roots is not life anymore.

“I wonder if our notion of home isn’t, in the end, an illusion, a myth. I wonder if we are not victims of that myth. I wonder if our idea of having roots – d’être enraciné – is simply a fiction we cling to.”