Back in November 2001, while on a US book tour, I found myself in Madison, the state capital of Wisconsin. The city felt rather unwelcoming: a grid of chilly avenues radiated from around the capitol building – another copy of the original in Washington that sits on an isthmus between two lakes, from which still colder winds blew in. Checking into my hotel, which was opposite a grim-looking convention centre, I noticed a flyer on the reception desk that

proclaimed: “Tonight! At the Convention Centre, Madison, Bob Dylon and His Band!”

I pointed this out to the receptionist: “Is this some sort of tribute act, or is it a misspelling?”

“It’s Bob Dylon,” she said. “I don’t know anything about a misspelling.”

“So,” I persisted, “the Bob Dylon who energised the civil rights movement in the 1960s – the Bob Dylon whose songs inspired a generation, the Bob Dylon who ‘went electric’ and was accused of folkie heresy, the Bob Dylon who’s gone in and out of fashion over decades now.”

“Yeah, like I say,” the receptionist bland-sided me, “Bob Dylon – do you want tickets for the show, there are plenty available?”

That this prophet should be unknown in his own country (Madison is 350 miles from Duluth where Dylan was born) seemed at once disorienting and reassuring. Obviously, I couldn’t go to the gig, but given his own poor ticket sales I felt a bit better that my own performance was attended by three buck-toothed teenagers wearing scaffolding-like braces, and an old man with a dog.

After declaiming for a while, I went out into the head-aching evening and looked for a restaurant. The atmosphere in the States that autumn was understandably grim: when I’d arrived in New York, there’d been a vast

tatterdemalion of handwritten notices on the walls of Grand Central, pleading for information about loved ones lost in the attacks on the Twin Towers. Downtown in Union Square, a group of Tibetan Buddhist monks in orange robes were saying prayers to mark the end of the bardo – the period of 40 days during which dead souls exist between incarnations, undergoing a terrifying series of visions and metamorphoses.

Most of the restaurants in Madison were empty, but there was – somewhat bizarrely – an Afghan one that was packed. My assumption was that all the left-leaning liberals in the city had descended on it as a strange form of solidarity: everyone knew that the country was about to be attacked by America and its allies, and many could already discern what a disaster it was likely to be. I couldn’t face such politicised noshing – so wandered for a while longer, wondering if some answer to mankind’s malevolence was to be found in the frigid zephyrs, before capitulating to a garden salad from McDonald’s then heading to bed.

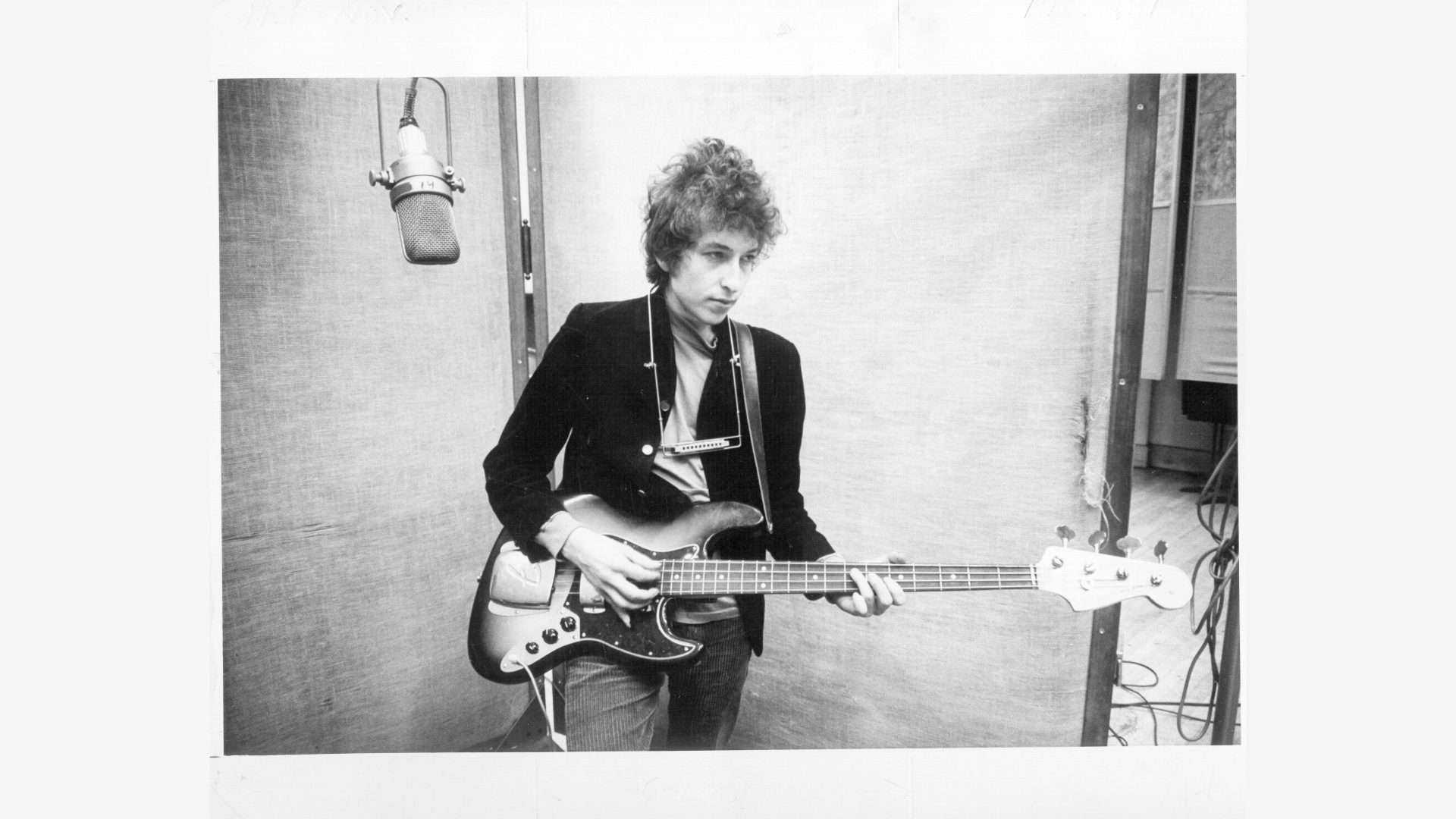

This bathetic episode repeated on me (as, no doubt, did the garden salad) when I read last week that a new recording of Dylan’s Blowin’ in the Wind was up for auction at Christie’s in London, with an estimated sale price nudging up towards a million smackers. Laid down in Nashville and LA last year, by Dylan and his long-established band, this is a platter that prima facie matters because there will only ever be a single copy. The disc itself is synthesised from the materials with which compact discs and vinyl ones are made, so – its originators claim – representing the greatest possible fidelity.

At one level, you can’t help admiring the octogenarian – his life, played out in the full glare of the media, has embodied a series of visions and metamorphoses, which while perhaps not terrifying, must have been difficult to live through. And then there’s the never-ending tour he was engaged on when our paths crossed in Madison, but which had, finally, to be terminated because of the pandemic. At one level the million-pound single is a way of continuing the Dylan-go-round in another way – but at the same time as it instantiates this ceaseless creative movement, it also, according to its creator, long-time Dylan collaborator and sideman T Bone Burnett, has the aura artworks embodied before their technological reproducibility.

In an interview he said that the recording session was itself “holy”, and that the track was lain down, in effect, in one take. As to the stratospheric price asked for this bizarre artefact: “We’re only making one because we view this work as the equivalent of an oil painting.” But it isn’t an oil painting, T Bone, it’s a record: you can’t sit and look at it for hours, you can only play it for a few minutes… then play it again and again. And surely after a few revolutions, whatever the outstanding fidelity of the recording, its buyer

should understand the answer blowing in this afflatus of affluence: you may have made a sound financial investment, but when it comes to aesthetics, you’ve been had.