The war in Ukraine continues despite on-off peace talks. Nuclear powers India and Pakistan are currently in a stand-off that could reignite into conflict. And who knows what will happen in the Middle East, given Benjamin Netanyahu’s destruction of Gaza and his many probable war crimes, including using the starvation of Palestinian civilians as a weapon against Hamas. In a recent survey before VE Day, around half the respondents in Britain, Spain, France, Germany and Italy said they believed a third world war within a decade to be very or fairly likely.

In his first Sunday address to the Vatican, Pope Leo XIV appealed to world leaders to seek peace. His words rang out over the huge crowds in St Peter’s Square: “No more war, never again war.”

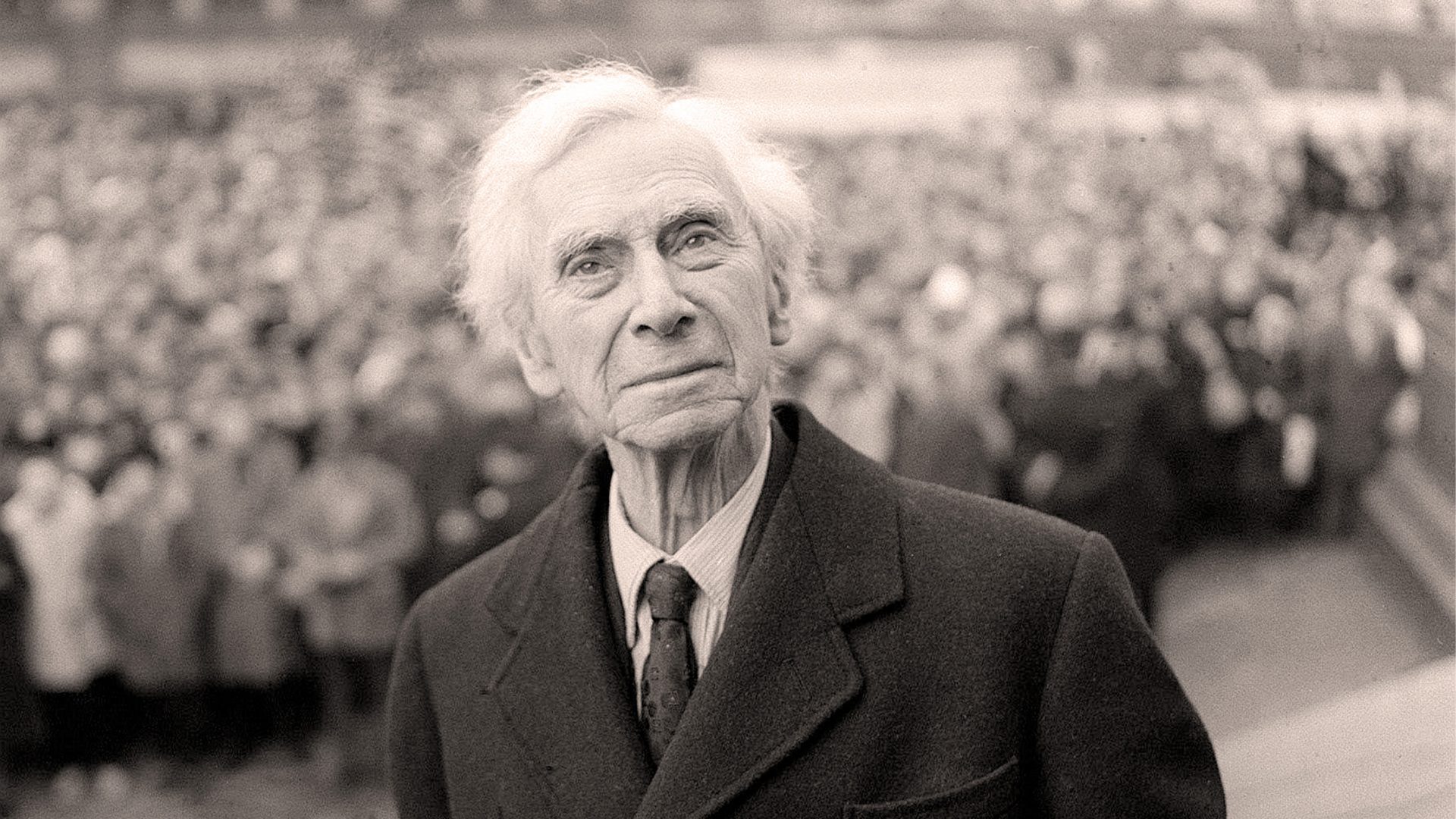

Many secular philosophers have opposed war and particular wars, but Bertrand Russell stands in a class apart. Born into the aristocracy in 1872, he began his career in Cambridge as a brilliant mathematician and logician.

In the three-volumed Principia Mathematica, which he wrote with Alfred North Whitehead, he undertook the herculean task of consistently reducing all mathematics to logic. He looked set to become a lifelong academic of great distinction and was promised a fellowship at Trinity College, but his anti-clerical and agnostic views were well-known, and he was passed over.

During the first world war, Russell’s pacifism and campaigning on behalf of conscientious objectors led to his expulsion from the college in 1916 following a conviction under the Defence of the Realm Act. Then in 1918 he spent six months in Brixton jail for lecturing against the US joining the war.

He used this time to write a book about mathematical philosophy. He later described his fellow prisoners as “in no way morally inferior to the rest of the population, though they were on the whole slightly below the usual level of intelligence as was shown by their having been caught.”

Many conscientious objectors are absolute pacifists who believe that all war is morally wrong in every conceivable circumstance. For them, there can never be a justification for any war or for taking part in it.

Russell hated wars because they brought out the worst in humanity, caused immense suffering, set civilisation back, and were often uncontrollable once started. But he resented being typecast as an absolute pacifist and made clear that although most wars are futile, “some wars, a very few, are justified, even necessary”.

He was a consequentialist thinker – and believed that in some very unusual circumstances, violence could be a means to a good end. He counted the second world war among these since Nazi domination would have been even worse than war.

After the second world war, however, Russell devoted his considerable energy to the cause of peace. He argued for the need for a world government to take control of the nuclear situation. He understood both the science and politics of atomic weaponry and feared that a simple error could trigger catastrophe for humanity.

He was a founder member and the first president of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, which argued for unilaterally giving up weapons. Then, in 1960, he set up the Committee of 100 for Civil Disobedience, who were prepared to break the law in protest against the British government’s commitment to nuclear weapons.

There is a long tradition of morally motivated civil disobedience, breaking laws to draw attention to injustice. Russell hoped that large-scale law-breaking would deflect the British government from its nuclear policies, saying: “If all those who disapprove of government policy were to join in massive demonstrations of civil disobedience, they could render governmental folly impossible and compel the so-called statesmen to acquiesce in measures that would make human survival possible.”

In September 1961, aged 89, he found himself back in Brixton, this time for a breach of the peace at a sit-down anti-Polaris protest near the Ministry of Defence. The magistrate offered him the chance of avoiding jail if he would promise good behaviour. Russell, feisty as ever, declined, saying “No, I won’t!” The subsequent press coverage did wonders for the cause.

Russell must have felt like Cassandra, though. He believed that only a world government should have access to nuclear weapons, and every other country should be forced to disarm to avert disaster. Philosophers, he declared polemically in 1964, had a duty to give up philosophy altogether and to campaign to stop nuclear war.

They didn’t, and his worst fears haven’t been realised. But let’s not be complacent. They still could be.