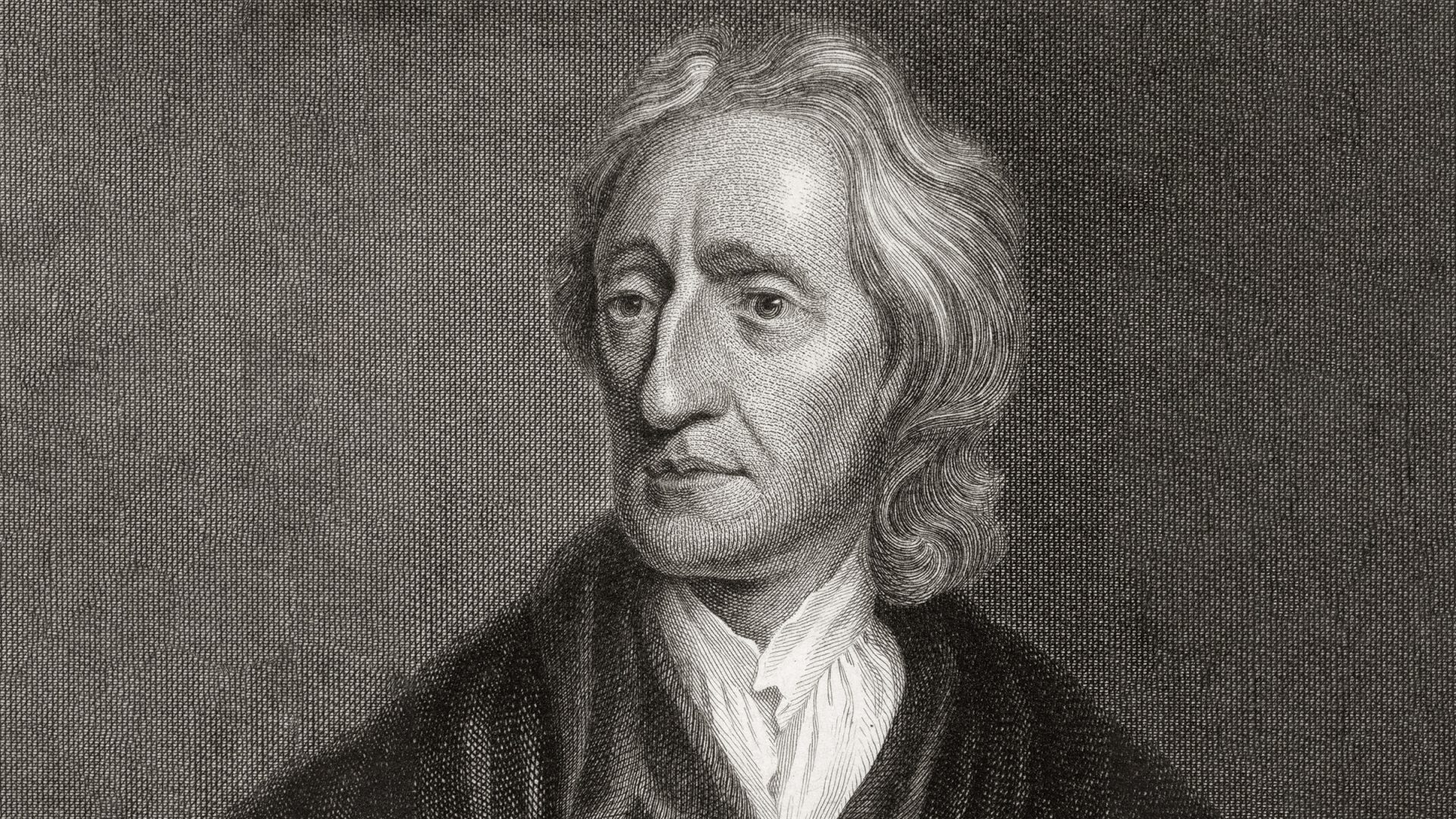

John Locke declared the mind of a child to be a tabula rasa, a blank slate, on which experience and reflection write. There are no innate ideas. The senses provide everything we can ever know or understand.

Locke’s empiricism lies behind the most famous experiment in home schooling in the history of philosophy. John Stuart Mill, born on May 20, 1806, was its product, achievement, or victim, depending on how you view it. His father, James, a freelance radical writer with strong views and a ferocious work ethic, believed that by educating his son according to strict principles, and by isolating him from anything that could lead him astray (essentially, other children except for his siblings), John would reach the intellectual potential he believed all healthy children had within them.

He started learning Ancient Greek from flashcards aged three, and was soon translating Herodotus and Xenophon. He’d sit across the table from his father, who was working on a book. When he reached a word he didn’t understand, he’d interrupt his father for a definition. His evenings were devoted to learning arithmetic. As he progressed, still a child, he had to teach his sisters Greek, an activity which he found onerous but which greatly improved his understanding of what he’d already learned. At eight, now with an excellent grasp of Greek, he turned to Latin and grappled with a reading list that many university students would find challenging.

On long walks with his father, this little prodigy would discuss what he had read. Mill senior didn’t cram him – far from it. He wanted him to understand, not just parrot the ideas he encountered. He taught him logic and its practical uses in dissecting mistakes in argument, encouraging his protégé to think through problems for himself rather than to recite answers and positions. John also spent time with his father’s friend Jeremy Bentham, the quirky yet brilliant utilitarian thinker and law reformer: a second workaholic as role model and mentor.

John’s long hours of study, debate and teaching paid off, in that aged 14 he was by his own reckoning 25 years ahead of his contemporaries in his studies, having mastered ancient and contemporary languages and high-level mathematics. Still a teenager, he had an in-depth knowledge of most of the major works in a wide variety of subjects, all of which he’d read in their original languages. He could and did argue intelligently with the greatest thinkers of his day. However, as is not so unusual when home-schooled children are removed from wider society, his emotional development was skewed, despite his father’s good intentions.

James Mill was temperamentally cold and often irritable, not one to express love or affection. If a child cried, for example, he wouldn’t comfort them because he felt that would encourage them to think that crying would always get that reward. His aim was to nurture a rational being with a firm commitment to the utilitarian cause of maximising happiness for the greatest number of people. We get a glimpse of Harriet Mill, John’s mother, whom John rarely mentioned, from a passage in a draft of his Autobiography (subsequently deleted) where he describes growing up “in the absence of love and in the presence of fear”, from which he might have been saved had she been more warm-hearted. In her defence, she was mother to nine children and was probably in a state of physical exhaustion much of the time.

Aged 20, John had a mental health crisis. Its immediate cause was overwork. Obsessive analytic thinking had worn away his feelings. He realised that even if everything he was striving for politically and intellectually were achieved, it would bring him no joy whatsoever. He became cut-off, affectless, depressed. The clouds only began to lift when he read a passage from the playwright Marmontel’s memoir, describing his father’s sudden death. It doesn’t take much psychological insight to appreciate why that particular scenario stirred his feelings.

He gradually recovered, aided by the realisation that seeking happiness makes it less likely you will find it: “Ask yourself whether you are happy and you cease to be so,” he wrote – a wise observation. In Wordsworth’s poetry he rediscovered his love of beauty in the natural world, and life got much better for him.

Nevertheless, he always bore the scars of being his father’s educational experiment. If the price of genius is the loss of childhood, that’s far too high a price for anyone to pay. The end doesn’t always justify the means.