Heraclitus believed that no one could step into the same river twice. That’s because both the river and the person will have changed. You might imagine that the river is the same one you visited previously, and that you are the same person you were, but, he implied, any apparent sameness is illusory. That’s because everything is in flux, everything is changing.

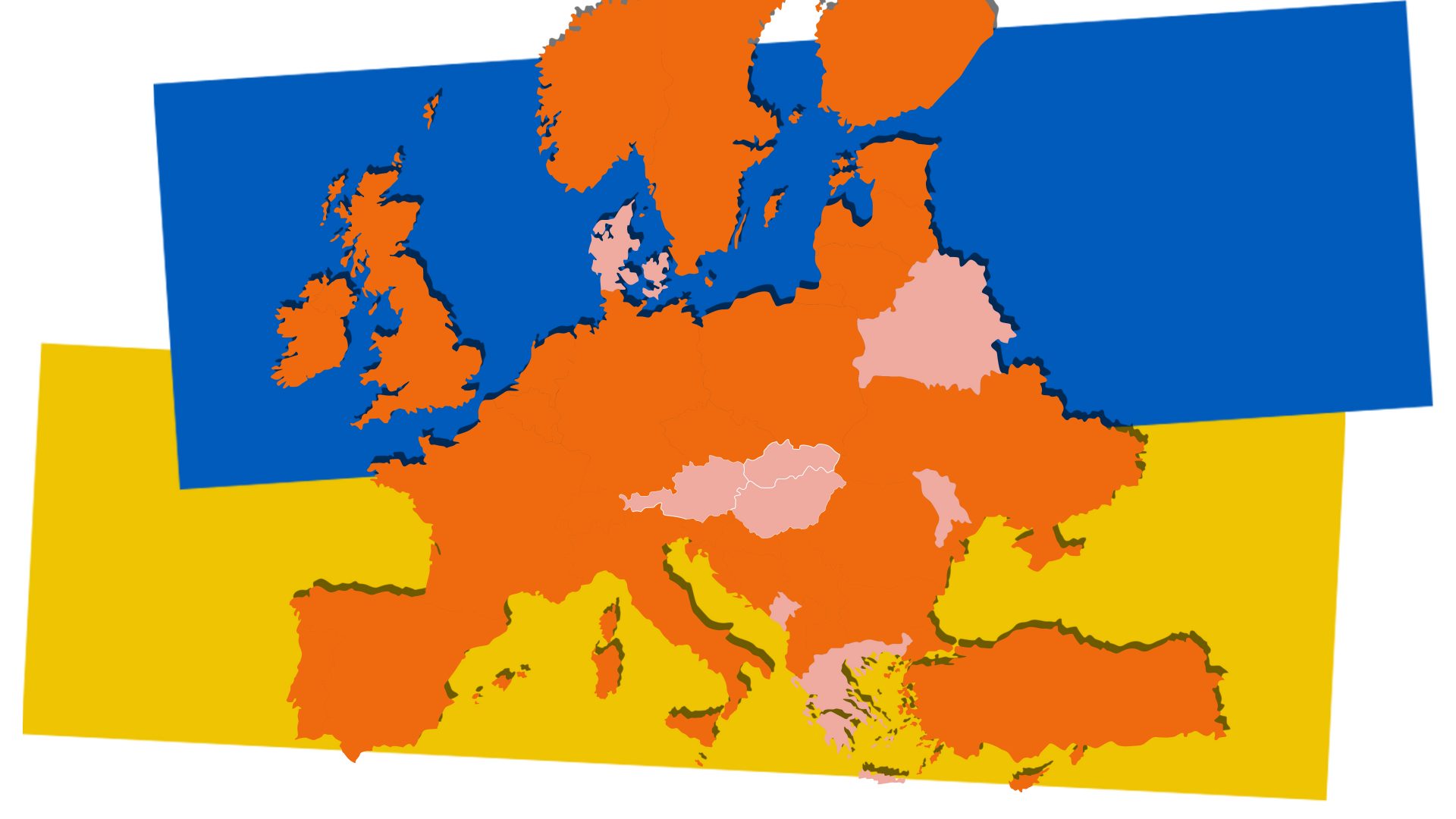

This year many European rivers have changed so much that no one could be under the illusion they were stepping into the same river as before. In some places there’s no longer any river to step into, only a trickle of water surrounded by patches of cracked earth. Spain and Italy have been particularly hard hit. Agricultural yields have been poor. Lakes and reservoirs are at historically low levels, both there and in neighbouring countries.

But even in the UK, where light rain is expected this week, supplies are drying up, hosepipe bans are still in place, lawns look dead.

While most of Europe remains parched, floods have displaced more than a million people in Pakistan. Many have died. It doesn’t feel right to call this a natural disaster as it’s the result of global warming – it’s a human-caused disaster. Meanwhile in Greenland the ice cap is melting faster than expected. Scientists predict that sea levels will rise rapidly over the rest of the century, threatening many coastal cities.

Heraclitus was right that everything is changing. We need to face up to this and change rapidly, too. In particular we need to change our attitudes to water, how we ensure that everyone has access to it, how we safeguard people, animals, and places against flooding, how we prevent water pollution and waste.

These are not just questions for scientists and engineers. Underlying all of them are fundamental philosophical questions about how we want to live, including questions about our responsibilities to fellow human beings regardless of whether they happen to be in the same city or country as us.

Beyond all this, though, is there anything water can teach us? Is there anything we can learn from water? These might seem strange questions to ask, but in eastern philosophy water has been held in high respect, something to emulate even. In the Daodejing, the sage Laozi advocates wuewei, the art of unforced effortless action in harmony with nature. In chapter eight, we are told that the highest good is like water, since water benefits living creatures.

The martial artist and film star Bruce Lee, perhaps influenced by a memory of these lines, told us “Be like water, my friend”.

Lee, who had studied philosophy at the University of Washington, describes coming to a newfound respect for water. His instructor, Yip Man, told him to stop asserting himself against nature, to aim instead to achieve a state of detachment that would allow spontaneous responses. Lee’s problem, though, was that every time he told himself to relax, that order to himself made him even less relaxed.

Taking a break from training on a boat out at sea, Lee let out his frustration. He punched the water. At that instant he had an epiphany. He’d hit the water, but it didn’t hurt the water. Water only seemed weak, but it could wear away the hardest substances in the world. It was adaptable, it changed shape as it needed to, and slipped away between the cracks. It could be subtle, or it could break through with a crash. He suddenly realised that he wanted to be like water – as a fighter, but also as a man. He wanted to be flexible to circumstance, ready to respond to whatever situation he found himself in. He wanted this to be his nature, and for his thoughts to be like the reflection of a bird flying over the water. He wanted to stop overthinking things and to become like the water.

Should we strive to be more like water? Perhaps. A respect for the forces of nature and a readiness to work with them rather than against them, a willingness to see what is in front of us rather than to import formulaic responses that worked in the past, these would be good for humanity.

But we live in a complex interdependent world and determining the right course of action towards the effects of climate change now is far from simple. Relaxing and going with the flow isn’t a viable option at a political level. Collectively we need to think hard, not sideline thought, and we need to adapt. Fast.