The security guard vaping disconsolately outside the empty Russian Pavilion might have expected to attract a bit more interest as the first visitors arrived at the opening of the 59th Venice Biennale, the world’s biggest and most prestigious art extravaganza.

Abandoned following the resignations of its curators and artists in February, Russia’s failed offering was in contrast to the spirited presence of Ukraine, which as well as a popular and by all accounts successful pavilion, created an installation called Piazza Ukraine and rounded off preview week with a video address by President Zelensky, who said: “Art can tell the world things that cannot be shared otherwise.”

But despite early speculation about the impact of Russia’s absence, geopolitics were thrust aside as festivities got under way: bespoke tote bags were coveted, Aperol spritzes were downed and ludicrous outfits were paraded; air kissing resumed unhindered by face masks.

Delayed for a year by Covid, this edition, the first since 2019, opened with an unstoppable sense of purpose. The experience of living through pandemic, climate crisis, and a rapidly changing technological landscape has hastened the move away from a world view with “Rational Man” at its centre, and towards the exploration of other structures and identities – both personal and collective.

To this end, of the 213 contemporary and historical artists represented, only

a smattering are male: this is no token gesture, and the Biennale, curated by

the New York-based Italian Cecilia Alemani, may even come to mark a key moment in the liberation of the art world from almost total domination by

white men.

Fidan Akhundova, a young sculptor from Azerbaijan’s all-female delegation, cautiously hopes so: she lives in Berlin, a more tolerant place than her home country, and feels encouraged by Azerbaijan’s championing of female artists. Still, she has serious reservations: “I don’t want to lie about the situation, I want to speak the truth and this is hard. Of course it’s a good sign, but is it real, or is it a show? We were told we could not draw a penis, and when I told the curator I was going to do a female body, he thought it would be better if it

had no sexual organs.”

In the end, Akhundova prevailed and Saltation, a small wax female nude, isolated but strong atop a huge wax edifice, is as much a victory for freedom of expression as it is a personal triumph for the artist. Its depiction of a woman struggling but persevering against a faceless adversary might be autobiographical, but it also addresses wider issues of female oppression in a patriarchal society, where selective abortion can still deprive females of the right to life, and where women can expect, writes Akhundova about her sculpture, to be turned into a “dependant, non-self-acting person”.

The galvanising effects of shared histories and experiences provide common ground for Britain and the US, which are each represented for the first time by black women, both of whom were presented with a Golden Lion. Simone Leigh has dramatically reinvented the US pavilion as a traditional African house, while Sonia Boyce has created a multi-room video installation, Feeling Her Way, in which five black female singers improvise together at Abbey Road Studios. Boyce’s focus on shared experience takes on a metaphysical aspect, as her films of five singers use performance to sift through our memories and emotions, individual and shared, focusing, she says, on “human responses… how to learn, how to listen, how to watch things unfold with other people.”

Both artists conjure worlds that are only partially located on terra firma: for the most part they exist in our memories and imaginations, places that take on central importance in the main exhibition in the Giardini’s central pavilion and continuing in the nearby Arsenale, the historic shipyard that has, since 1980, been part of the Biennale’s ever-growing footprint.

The Milk of Dreams takes its title and its inspiration from a children’s book by the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, whose tales of magic and metamorphosis explore the transformational qualities of both nature and technology in an often frightening, rapidly changing world.

Corte/British Council)

The exhibition pulls together strands from across time and place, connecting the Dadaist puppets of Sophie Taeuber-Arp with the even less well-known doll-like creations of Ovartaci, who was born Louis Marcussen in 1894, and underwent gender-reassignment surgery in 1957 having been committed to a mental hospital 18 years previously. The dark fairy tales so central to Paula Rego’s work find an echo in Carrington’s sinister, absurd inventions.

Weaving historic examples with contemporary works from 58 different countries, The Milk of Dreams is both exciting and persuasive. In prioritising

female, and non-gender-conforming artists, it puts paid to the idea that an

account with only minimal male contributions is a hobbled one. The result is a rich, reinvigorated selection of work that adds dimension to previously familiar movements in art history – and notably surrealism.

Formerly the Nordic Pavilion, the Sámi Pavilion highlights the trauma and displacement inflicted on the indigenous reindeer-herders of Sápmi, a region that covers parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. A folksy

style runs through a cheerfully priapic Latvian offering, which includes

ceramic boobs, and what an attendant called a “boner vase” featuring pornographic illustrations.

Spain’s oddly boring offering casts the pavilion itself as difficult territory:

having concluded that its orientation is slightly off, Ignasi Aballí has set

about installing a corrected version.

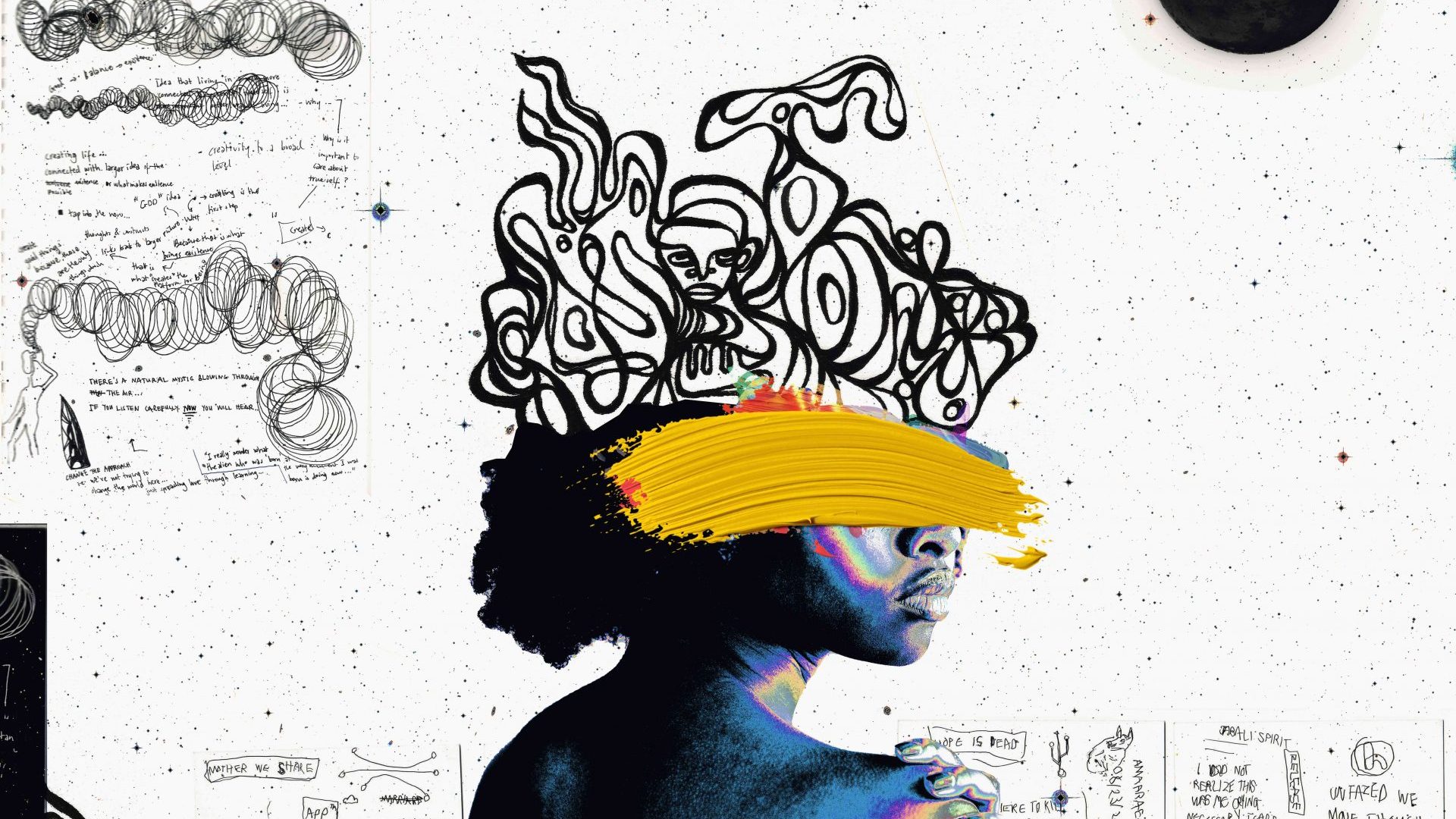

After shaking up the Biennale’s “sea of whiteness” with its 2019 debut, Ghana

returns a second time with an exhibition that explores alternative realities

through machine learning and traditional storytelling, inviting a reconsideration of the museum as a place where identities are honed, ideas

that are already enshrined in Ghana’s Mobile Museum programme, of

increasing importance as the country reshapes its post-colonial identity.

Things wouldn’t be quite right if there weren’t at least a hint of artistic

hubris on display, and perhaps in direct response to the predominantly

female focus, Anish Kapoor and Anselm Kiefer have gone all out to get

our attention with what may well be career-defining magna opera. Kiefer

gives us sublime shopping trolleys; Kapoor fires offal-like paint through a

cannon: each can rest assured that they haven’t been forgotten.

The 59th Venice Biennale, curated by Cecilia Alemani, runs until November 27, 2022

Florence Hallett is a freelance art writer and critic