The highest mountain in the world is Mount Everest, in the Himalayas. It is known in Nepali as Sagarmāthā, and in Tibetan as Chomolungma, “Mother Goddess of the World”.

I am old enough to remember clearly when the “British conquest of Everest” on May 29, 1953 was proudly announced to the world to coincide with the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on June 2. The news was broken by the Welsh journalist James (later Jan) Morris, who cleverly managed to conceal his scoop from all his other news rivals.

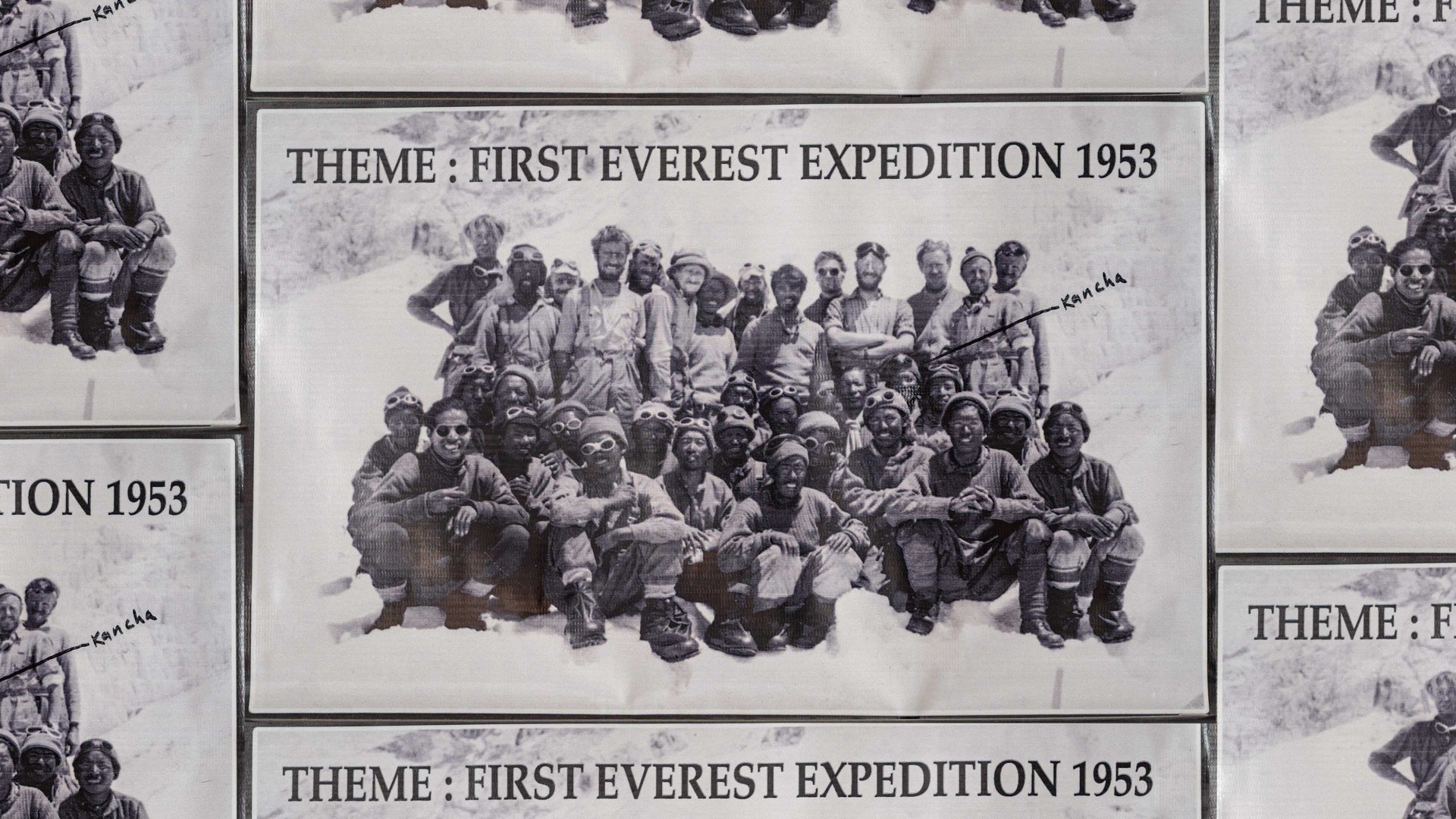

The Everest expedition was indeed a basically British undertaking, but the first two people ever known with certainty to have reached the summit of the great mountain were team members Edmund Hillary, a New Zealander, and Tenzing Norgay, who was probably Nepalese.

It seems that Tenzing’s parents came from Tibet but that he himself was born in Nepal. The family were members of the Buddhist Tibetic ethnic group known as the Sherpa, who speak a Tibetic language, also called Sherpa, which has about 150,000 speakers across Nepal, Sikkim and Tibet.

The summit of Everest, at 29,031ft or 8,849 metres (jointly declared by China and Nepal in 2020) above sea level, sits on the border between Tibet and Nepal. It is also on an important linguistic frontier between two language families.

The Nepalese language, or Nepali, is a member of the Indo-Aryan language family, which also includes Hindi and Panjabi. Nepali has about 19 million native speakers, mainly in Nepal but also in Bhutan, Burma and India. It is also spoken as the main second-language lingua franca across many parts of Nepal.

Tibetan, on the other hand, is a member of the very large Tibeto-Burman family of languages which are spoken in Burma, China and India as well as in Nepal.

British readers may find themselves uncertain as to how to pronounce names such as Qomolangma and Sagarmāthā, but in fact it is the English-language name Everest whose pronunciation we should perhaps be more interested in. This is because, it could be argued, we always get it wrong.

The peak is named after Sir George Everest (1790-1866), a Welsh geographer and surveyor who was surveyor general of British India from 1830 to 1843. Apparently he did not want to receive this honour, believing that it would be more appropriate to use a local Nepali or Tibetan name. But in spite of these misgivings, this appellation for the mountain still survives, and today it must be one of the best known toponyms in the whole world.

Sir George’s family name, now also transferred to the mountain, is not a very common one. In Britain and Ireland, there are currently about 1,400 bearers of the name (including variants such as Everist, Everiss and Everix), with a small concentration in Kent. It is thought to derive from the French-language surname Devereux, originally d’Evereux, meaning “from (the town of) Évreux”, which is in Normandy, about 35 miles to the south of Rouen.

But Sir George and his family did not pronounce their name as “ever-rest”, as most of us do these days. If their family usage had prevailed, as arguably it should have done, the highest point on the surface of our planet would now be known to all as the summit of Mount “Eve-rest”.

BURMA

In 1989, the Burmese military dictatorship decreed a change in many English-language names dating back to Burma’s British colonial past, including the renaming of the country itself from Burma to Myanmar. Many democratic opposition groups and ethnic minorities continue to use “Burma” as the country’s name because they do not accept the legitimacy of the unelected military government.