An 18-year-old girl, of high-class birth but fallen on hard times, who, three years previously, entered into a spurious marriage with a foreign naval officer and – after he left – bore him a child, has nonetheless waited for him to return despite all the evidence of his bad faith. Looking down from her hilltop house, she sees a ship sailing into the harbour and cries out: “White, white… the American stars and stripes!… ’Tis putting into port to anchor!” And taking up a telescope, asks her maid to “Keep my hand steady that I may read the name.

“The name,” she panics, “where is it?” then experiences a moment of almost spiritual affirmation, crying out: “Here it is: Abraham Lincoln!” Except that this being grand opera, she doesn’t say the name loudly so much as extract every last particle of salvational meaning she can from its elongated phonemes, thus: “Aaaaabraaaahaaaam Liiiiinnnnccccooooollllnnnn!”

Culturally knowledgeable TNE readers that you are, most of you will

have realised where this takes place – Nagasaki, Japan – before this, the

climax of the second act of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly was reached; but my

purpose in teasing it out in this way is to emphasise quite how pointed the

critique of western imperialism is. The wronged young Japanese woman

thinks the ship’s very name is a harbinger of deliverance; and what could be more devastating, given that it’s also the name of the so-called Great Emancipator himself, whose principles and actions are seen as directly leading to the liberation of America’s black slaves.

The irony – given that Abraham Lincoln conveys Cio-Cio San’s nemesis, the errant and now bigamous Lieutenant Pinkerton – would not have been lost on those who witnessed the opera’s first productions in the 1900s. Yet how much more resonant it seems now, given the parlous state of contemporary American liberalism, and the interracial conflicts, which, over 100 years later, continue to plague the American body-politic.

Given all this, it seems strange that the Royal Opera House’s current production of the opera should have become a sort of test case for a new approach to some of the most celebrated works in the repertoire that

its director, Oli Mears, has dubbed “colour conscious”. Taking Madama Butterfly as exemplary in this respect, he describes it in an article for the Guardian as “a nasty story” that raises the troubling question of whether

depicting Pinkerton’s misogynistic behaviour somehow endorses it; moreover, the “racial dimension” of the piece feels, he writes, “too hot to handle”.

So, in order to not just handle but create a production of the piece, Mears and his colleagues have engaged specialists with a view to rendering Madama Butterfly – which was originally conceived in this way by Puccini himself – a yet more effective synergy of a European art form with Japanese traditional culture. Experts on everything from deportment to dance, and from etiquette to clothing have been brought in to render the piece more authentically Japanese. The results are beautiful and intense – a definite artistic advance on the 2003 production directed by Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier, of which this is the sixth revival.

But it isn’t from the aesthetic angle that the revival director, Daniel Dooner, seems to have approached the opera. Speaking to me, Mears further developed this perspective; first making the point that the standard repertoire is entirely written by dead white men, then quoting George Orwell to the effect that “all art is politics” before seemingly contradicting himself: “What would be unfortunate would be if one were to make any blanket statements, or ideological comments that only one person – or one race – can perform this role; I think that would be very reductive.”

So, the perception that all art is political relates to a certain sort of politics; Mears derides “political correctness”, yet his own vision of opera as a “progressive” artform certainly rests on a conviction that forms of “upstream” cultural inclusivity can enable… well, what, precisely? Social inclusion? Economic levelling?

I pushed him on this precise point: wasn’t it a bit, um, rich, imagining that ethically cleansing the wealthy would have a genuine political impact? What

about redistributing to the masses the Ruinart Blanc de Blancs (£95 per bottle) the ROH sells its tony punters by the bucketful?

Mears was bullish about believing, personally, in a more equitable society with greater redistribution of wealth – but forgive me a little cynicism whenever I hear someone on a six-figure salary come on like a liberal version of St Augustine: “Lord, pay us all the same… but not yet.”

It’s been a class-conscious time for opera, with Dominic Raab seemingly

being hoisted by his own privileged petard last month, after labelling his

opposite number at PMQs, Angela Rayner, a “champagne socialist” for

having attended a production of The Marriage of Figaro at Glyndebourne on the same day that the train drivers went on strike.

Rayner hit back at Raab in truly operatic fashion, saying, “My advice to the deputy PM is to cut out the snobbery and brush up on his opera. The Marriage of Figaro is the story of a working-class woman who gets the better of a privileged but dim-witted villain.”

She then went on to argue: “Judging by his own performance today, Dominic Raab could learn a lesson about opening up the arts to everyone, whatever their background.” Which is really the standard operating protocol for exactly the sort of champagne socialist he accused her of being: I’m here in my evening dress drinking champagne at the opera, and that’s OK because it’s where I want everyone else to be as well.

However, the truth is Covent Garden simply wouldn’t be Covent Garden if as

many people went as attended, say, the recent Adele concerts in Hyde Park –

which was the price comparison Mears made to me when he wanted to emphasise the relative cheapness of opera tickets. But I told him I positively wished my experience of his storied theatre to have this luxurious cast – that indeed, I held off going that often because of a fortuitous lockstep between my own restricted budget, and my desire for the experience to be luxurious in all senses. This he endorsed: “It is a magic portal to another world – and that’s something really special.”

Moreover, while he may utter the current – and in my view, plain wrong – shibboleth that “art thrives when everyone feels they can make it”, Mears doesn’t want to be a cultural gatekeeper whose citadel is breached by a mob.

I asked him exactly what criticisms of the existing production of Madama

Butterfly there had been and he was emphatic: “I don’t think there have been any complaints… I don’t think we as a cultural organisation should be driven by complaints, we should be driven by what the right thing to do is. We know that these topics are very charged right now… people have very strong feelings about it, and that’s why at the start of the process we opened it up to members of staff here.”

He went quiet when I suggested that while this may have been the case, nonetheless he – in common with many other established cultural commissars – was acting proactively, in fear of possible populist repercussions. While the aim of involving all his staff in making productions they can ethically endorse may be estimable – I bet given a choice they’d prefer to be on the same salary as him and put up with the solecisms in Madama Butterfly. I mused as to whether given this “conscientised” production of Puccini, the ROH would be revisiting the ethical dilemmas surrounding other famous works in the repertoire – Wagner and antisemitism sprang readily to mind.

Mears mused that this was, indeed, “really intriguing” given that “opera deals with the darkest places in the human psyche”, and argued that the problematic representation of women in the standard repertoire “needs to be interrogated”, before veering off into a consideration of audience dynamics since the pandemic: “They seem more sensitised – people are more edgy.”

He spoke of more problematic incidents with audience members, and I wondered at this point whether it was possible to disentangle the impact of Covid as against that of another pernicious acronym, to wit, Brexit?

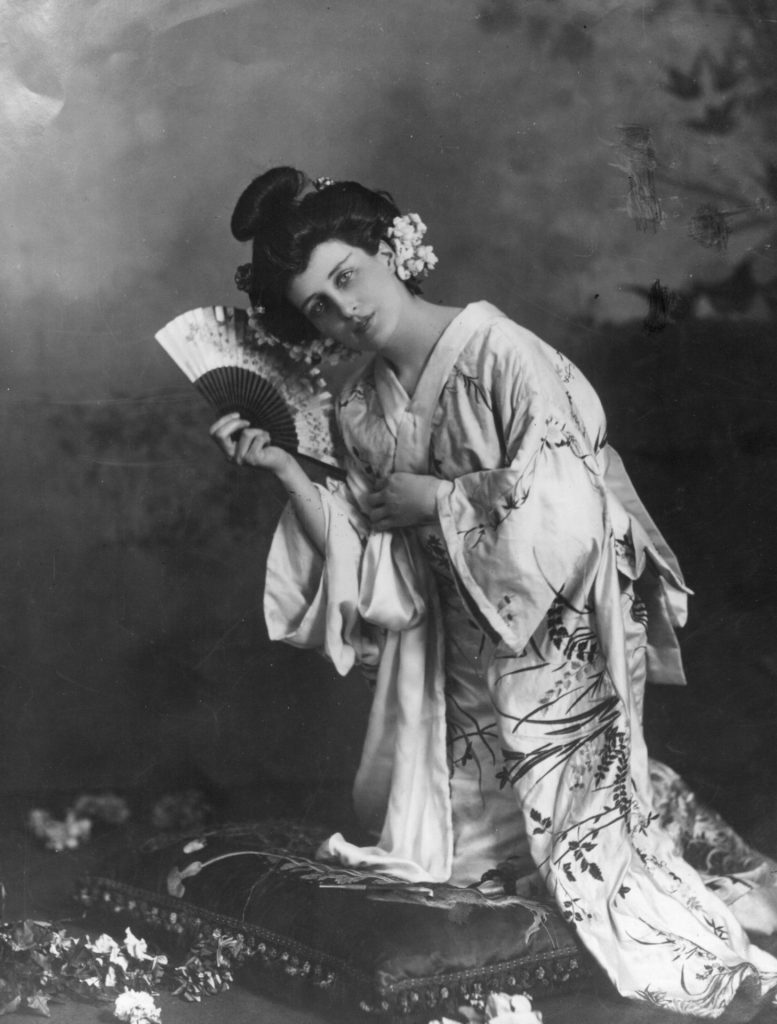

circa 1910. Photo by W. & D. Downey/Hulton Archive

Mears was predictably diplomatic: not wishing to parrot the “cliched defence” offered for current difficulties by those who were in favour, that “it’s impossible to disentangle the impact of Brexit from that of Covid and the war (in Ukraine)” – before doing precisely that. He conceded that leaving the EU has meant there’s a lot more paperwork to do when it comes to importing the highly skilled people the company requires – not just singers, directors and other musicians, but costume makers, set designers and all the rest.

However, he said: “The bigger impact is on British artists’ untrammelled access to Europe.” This is crucial in order that they get the necessary experience – but of course now they face “an absolute nightmare” in terms of paperwork.

This perspective was echoed by Richard Mantle, the director at Opera North. An offshoot of the English National Opera (ENO), Opera North inherited its parent company’s mission of singing entirely in English, and nurturing homegrown talent – but over the years, these aims have been modulated. First by technology: translated surtitles now make it possible for monoglot audiences to engage with polyglot libretti; and second – although neither director mentioned this – by the freer movement of European workers that

came during the last two decades of Britain’s EU membership.

Both men emphasised the specifically European character of opera – but neither was willing to join the dots and create a picture of an isolationist country cutting itself off from the talent wellspring of a major artform, brought here initially by Italians and Germans in the 17th century.

Nevertheless, for Mantle: “One of the anxieties I had was on behalf of British artists – whether they’d be able to get that freedom and flexibility of work in Europe… Not the top flight of artists that we have, they’ll always get work

internationally… But I’m concerned that developing artists might find it a bit more of a struggle.” Brexit, he said, had yet to have an impact when it came to importing artists: “We do cast from Australia and America, and we have thought twice about doing that because of the process we have to go through for visas and everything else… And we do bring people in from Europe, and that’s now making us think twice.”

But while the artistic recruitment may not be so much of a problem yet, he said, “there are other aspects of Brexit that are affecting us – availability of raw materials, staff and employment, I think is a big issue… coupled with the perfect storm of Covid… That really has disrupted the labour market in Britain and impacted on aspects of what we do.”

The labour market problems are uppermost in everyone’s minds – but it

was sobering to reflect along with Mantle on these very superstructural

impacts of the current baseline commodity shortages: “Getting raw materials to make productions, whether that’s wood… maybe even steel, material for costumes as well… that has become much more challenging, and obviously incredibly expensive.”

Neither Mantle nor Mears blamed Brexit and the pandemic entirely for this – the war in Ukraine was probably the supervening factor; but it all added up to a sense of greater isolation: as if British opera were to personify itself as Cio-Cio San, left behind to tragically commit artistic suicide on its right, tight little island.

Mantle told me the ENO’s recent production of Wagner’s Der Valkyrie had been unable to source the wood required to build the walls of the set, so had to rely on curtains instead – so perhaps an image of impermanence should be added to that of isolation.

And what of the drive for greater cultural sensitivity and authenticity –

might this be seen in part as compensating in advance for British opera’s potentially parochial status once the consequences of Brexit really do manifest? I don’t for a second doubt either man’s commitment to – as Mantle put it – “develop the artform, the artist and the audience”, and I’ve committed in advance to attend the premiere of Opera North’s new production of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, which the company is reconceiving as a cultural synthesis between Baroque singers and Indian musicians. However, as Mantle also acknowledged, the point at which so-called colourblind casting needs to cede to his colleagues’ new “conscious” conception is fiendishly hard to identify.

A conundrum that, for me, was epitomised on the night I saw Madama Butterfly by this: the lead singer for the role – who has received stunning

reviews, as has the production generally – was the internationally known Armenian prima donna Lianna Haroutounian. But the soprano I saw bring Cio-Cio San to life then put her to death had indeed been nurtured by the Royal Opera’s own young artists’ programme. Even so, I can’t help feeling that at least part of the extraordinary artistry she brought to the role – and which should have earned her more than the grudging semi-standing ovation the Covent Garden audience gave her – was a function of the fact that Eri Nakamura is… Japanese.