Migrants to Italy – the bee-eaters, the hoopoes, the golden orioles – start arriving about now. They fly north for the summer, on the lookout for nesting sites in Umbria, in the shadow of Monte Subasio.

It was on this mountain, which rises above Assisi and dominates Umbria’s green heart of Italy, that St Francis of Assisi, the merchant’s son born Giovanni di Bernardone, became overwhelmed by a love of the natural world that would underpin his life’s work. Birds, wolves, everything in the food chain in between, were, like the very sun and moon, equal partners in creation. Appealingly, to artists in particular, he is known to have preached to the very birds themselves.

His respect for the delicate balance of nature was echoed in 2015 by Pope Francis in his second encyclical letter. “Our common home is like a sister with whom we share our life,” he wrote. “This sister now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her.

“Saint Francis is the example par excellence of care for the vulnerable and of an integral ecology lived out joyfully and authentically,” the Pope decreed. “He is the patron saint of all who study and work in the area of ecology… He shows us just how inseparable the bond is between concern for nature, justice for the poor, commitment to society, and interior peace.”

Jorge Mario Bergoglio was born in Buenos Aires in 1936 and elected pope in 2013. The man on whom he has modelled his ministry, Giovanni di Bernardone, was born in Assisi in 1181 or 1182. And across the 800 years between the lives of the two Francises have unfolded chapters in the history of art, the evolving environmental movement, and the ethics of wealth and poverty.

The merchant’s son was to become known as il poverello, “the little poor man”. Calling himself Francis, he turned his back on comfort, founding an order that to this day espouses a simple life in tune with nature.

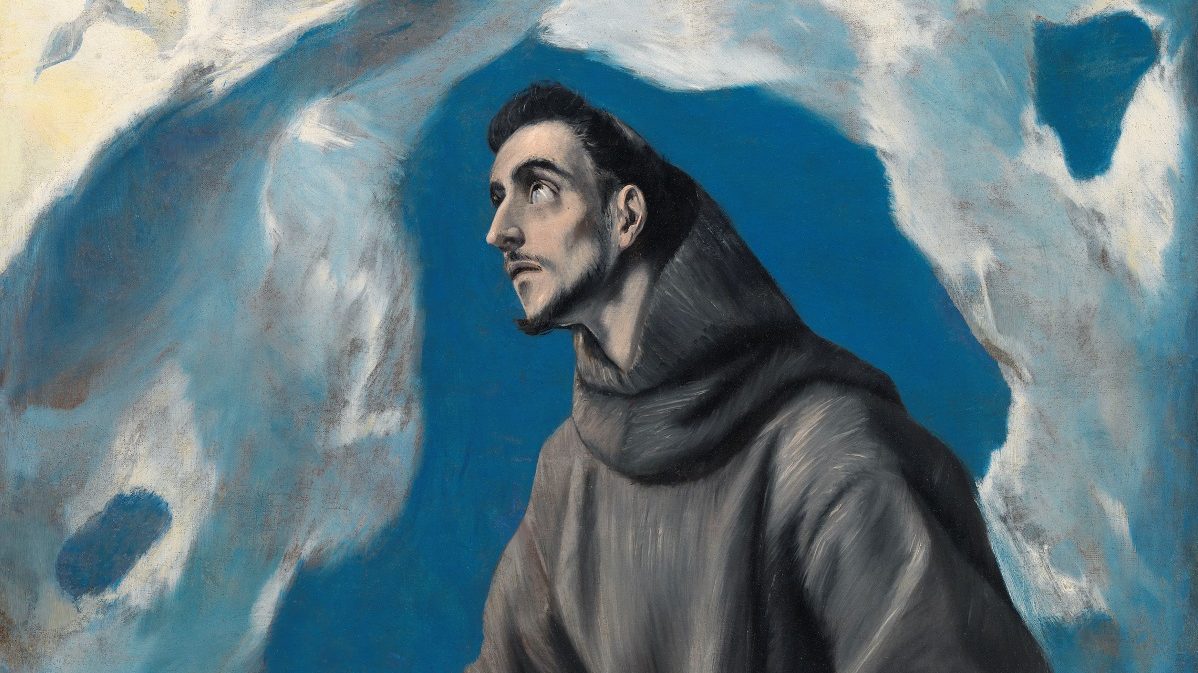

Paradoxically, the simple, possession-free life of St Francis has inspired innumerable valuable artworks; possibly as many as 22,000 within the first 100 years of his death. Some were embellished with gold. Many of those extant would today fetch vast sums on the open market: works by Francisco di Zurbarán in Spain, Sandro Botticelli in Italy, and Albrecht Dürer in Germany.

Regardless of a falling away from Christianity, the person and principles of Saint Francis continue to fascinate artists today. So, in an exhibition at the National Gallery in London opening on May 6, alongside medieval, renaissance and mannerist treasures there are works by modern masters: land artist Richard Long, sculptor Antony Gormley, painter Craigie Aitchison, and printmaker Andrea Büttner: her 2010 woodcut Vogelprodigt (Sermon to the Birds) will be in London.

Stanley Spencer’s Francis, pursued by a clutch of ducks and hens, is a stout friar, who outraged the hanging committee of the Royal Academy of Arts’ summer exhibition in 1935. There is even a 75-cent Marvel Comics publication, Francis, Brother of the Universe (1980), a garish but admiring frenzy of holy derring-do.

This concentration on a single personality, rather than an exploration of an artist or style, was to have opened in 2019, and has been many years in the making. But, says gallery director Gabriele Finaldi, for whom this project is very close to the heart, “every year is a Saint Francis year”.

The year 2023 marks 800 years since Francis’s mission was approved by the then Pope. It is also 800 years since an act that today seems commonplace, but which in its time was an innovation: the re-enactment, in the village of Greccio, near Rieti in the Lazio region, of the birth of Christ, complete with ox, ass and manger, a Franciscan gesture subsequently imitated in countless Christmas cribs and Nativity plays.

The precision of Francis’s chronology is borne out by contemporary accounts of his short adult life (he died at 44), by a rash of posthumous biographies, and by his own surviving documents, which, appropriately, include a drawing. The T-shaped Tau votive symbol that he favoured over the cross sprouts from a roughly bearded face. A facsimile of this, alongside many rather more polished works, loaned by galleries worldwide, augment the National Gallery’s own, numerous, St Francis works which will be at the heart of this unusual show.

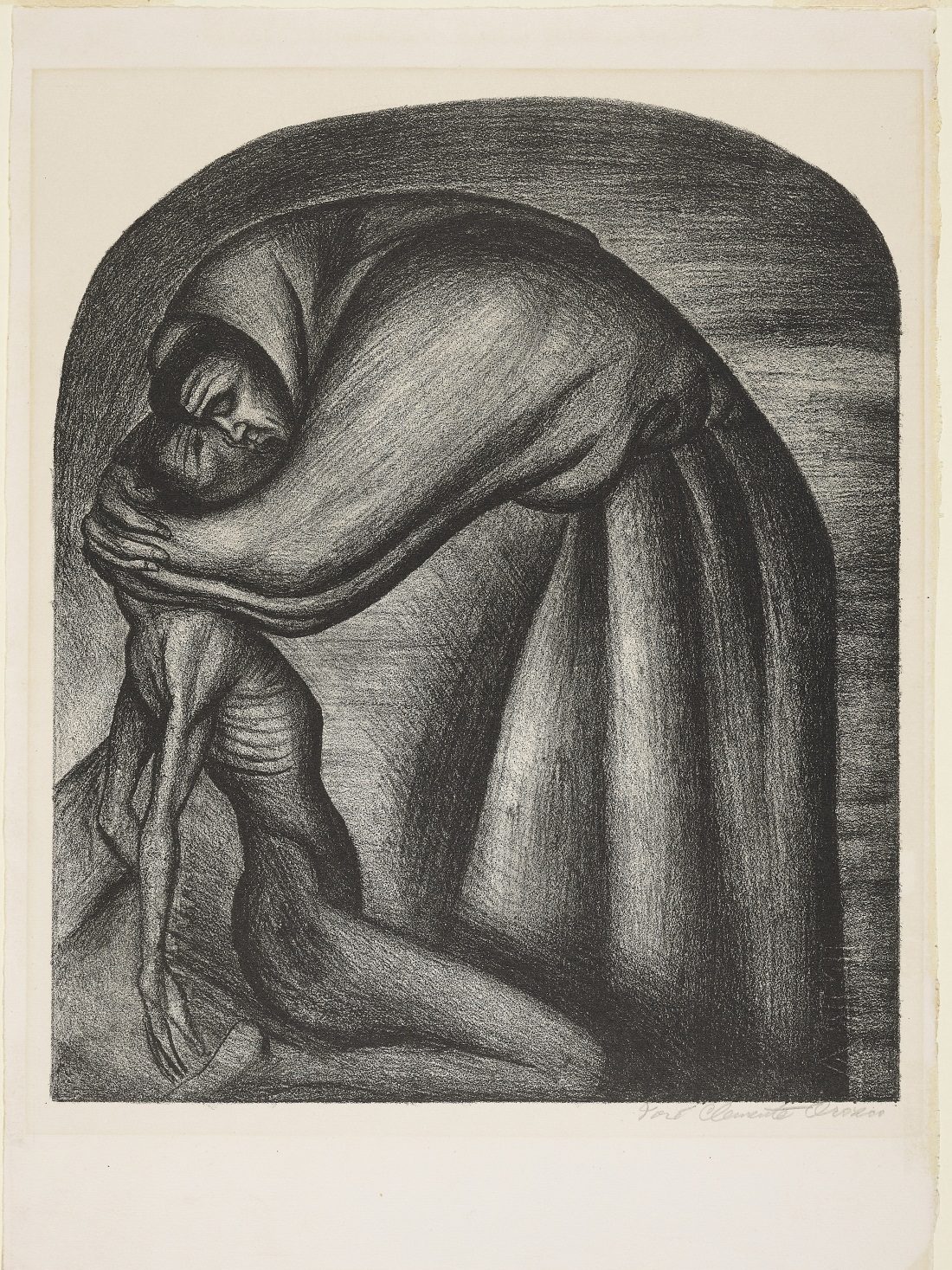

Photo: Trustees of the British Museum

And despite this apparent singularity, many topics far outside the Christian faith, and with applications in a secular world, will be raised by the hugely varied exhibits.

Although he wrote to followers and left a paper trail, St Francis was little tied to text, preferring acts of faith – such as living in poverty or caring for lepers – to theories. And he was unprecedentedly concerned, within the Christian faith, with re-evaluating mankind’s role within the universe.

His first notable act as he carved out a new future outside the family business was to strip himself of his smart young man’s clothing, a delectably dramatic scene for a painter. This is graphically portrayed in the cycle of frescos by Giotto in the Sacro Convento di San Francesco, the great basilica in Assisi, that attract art-lovers and pilgrims from all over the world.

The lavishly decorated walls of the upper and lower churches of this beautiful building illustrate most vividly the contrast between the hovels and rough-hewn rocks among which Francis chose to live, and the splendour of art, architecture and ceremony that radiate from this sacred space. And it is this series that marks a turning point in the history of art, prompting countless other narrative cycles, explains Finaldi, who co-curates the exhibition with Joost Joustra. Many others also tell the Franciscan story, notably in the church of Santa Croce in Florence and in Montefalco, near Assisi, where the town’s museum is wrapped around Benozzo Gozzoli’s life of Francis in the east end of the deconsecrated church of St Francesco.

But the works inspired by Francis or by the artistic tradition that his life story inspired are by no means limited to painting. The land artist Richard Long spent a week living rough on Mount Subasio – a mission that required permission from the first woman mayor of Assisi, Stefania Proietti – before creating a work especially for the National Gallery show. He is among a generation of artists who have responded to Francis the ecologist, rather than the man of God. That devotion to nature was expressed in the Canticle of the Sun, which embraces all creatures and all the elements of the natural world, including death itself, as equal partners in life.

The poverty that Francis espoused was manifested in the very basic garment he devised. Today, the loosely worn friar’s habit is automatically associated with the contemplative life, but in Francis’s time, it would have been considered crude and even outlandish wear for an educated man. Adapting the rough working clothes of a poor worker, he designed a shapeless, coarse habit in the shape of the Tau, its hood completing the outline of a cross. Several examples believed to be his still exist, battered, tattered and patched. One will come to London, on loan from Santa Croce in Florence.

Any scepticism about the authenticity of such relics is sidelined by the quality of artwork that the familiar and highly symbolic garb inspired. At polar opposites in this sartorial exploration are the Spanish artist Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1654)) and the Umbrian artist Alberto Burri (1915-1995). The former depicts the saint in deep contemplation inside his capacious and expressively draped garment, the painting refined and reverential. The latter referenced not the robe’s style but its shoddy fabric, in his series of artworks entitled Sacchi. In Sacco (1953), on loan to London, ripped and mismatched sacking cobbled together with rudimentary suturing (the artist was an army surgeon during the second world war) echoes Francis’s rejection of outward show.

Growing up in Città di Castello, a few kilometres from Assisi and with a Franciscan foundation in the town, like all modern Italian artists, Burri would have been immersed in his country’s artistic and religious history, Finaldi observes. In 1975, an exhibition of his works was held, most unusually, at the basilica in Assisi, a rare conflation of the building’s integral artworks with those of a contemporary artist.

While today’s observers may share Francis’s values – his care for the underprivileged and the environment – those may be based on humanitarian rather than Christian beliefs, and perhaps challenged by accounts of the saint’s receiving of the stigmata, the crucifixion wounds of Christ, at La Verna, high in the Tuscan hills.

The sculptor Antony Gormley meets this dilemma head-on in his Untitled (for Francis), purchased by the Tate in 1987. Working at an auction house in New York, Gormley would visit the Frick Collection, which owns a rare Giovanni Bellini painting depicting Francis, a figure who was revered in Gormley’s childhood home.

Visiting Assisi in his mid-20s, he was transfixed by one of the saint’s crude robes. His “body-cast”, made of plaster, fibreglass and lead panels, echo the fragmentary nature of the garment, and represent the stigmata – holes in the feet, hands and side – as eyes. The observer gets closer to the saint by literally seeing inside him.

Far from hiding away on hills and in huts from the onset of his mission, Francis travelled widely if briefly. In 1209 he set out for Rome, where he sought and received Pope Innocent III’s approval for the avowedly simple life of his fraternity that eschewed the riches of the church.

Ten years later he travelled to the Holy Land at the time of the Fifth Crusade, meeting and talking sympathetically in the besieged port of Damietta with the Sultan of Egypt, al-Malik al-Kamil. The sultan gave Francis an Italian-made gift, a gesture of cultural and interfaith respect. This ceremonial horn, now in Assisi and on loan to London, is another conspicuously lavish artefact somewhat at odds with the saint’s credo.

Then and now, the saint’s popularity is without borders. He was canonised within two years of his death, a strategic move that guaranteed a valuable and virtually uninterrupted flow of visitors from all over the world to his town and tomb.

Francis has had his detractors, including the German writer Goethe who, arriving in Assisi on his travels through Italy, ignored the basilica and recorded only his visit to the city’s Roman Temple of Minerva. Today, followers of St Francis face a paradox. To visit his places, to view even some of the countless works of art he inspired, requires international travel that contributes to climate crisis.

This exhibition offers one solution. With many works gathered uniquely under one roof, the bee-eaters, orioles and hoopoes can have the skies to themselves.

Saint Francis of Assisi is at the National Gallery, London, from May 6 to July 30, admission free.