Millions of people will be voting in the local elections on May 1 with little, if any, real knowledge of the local issues that should be influencing their ballot decisions. Beyond the party allegiances, or none, of the candidates, voters will be largely unaware of how the incumbents have behaved in office, where they have succeeded and failed, and what should be top of their priorities should they be elected.

In a fast-changing media landscape, UK local news coverage is one of the most hard-hit, and this poses a genuine threat to democracy, potentially more extreme and certainly more immediate than that now affecting the national media.

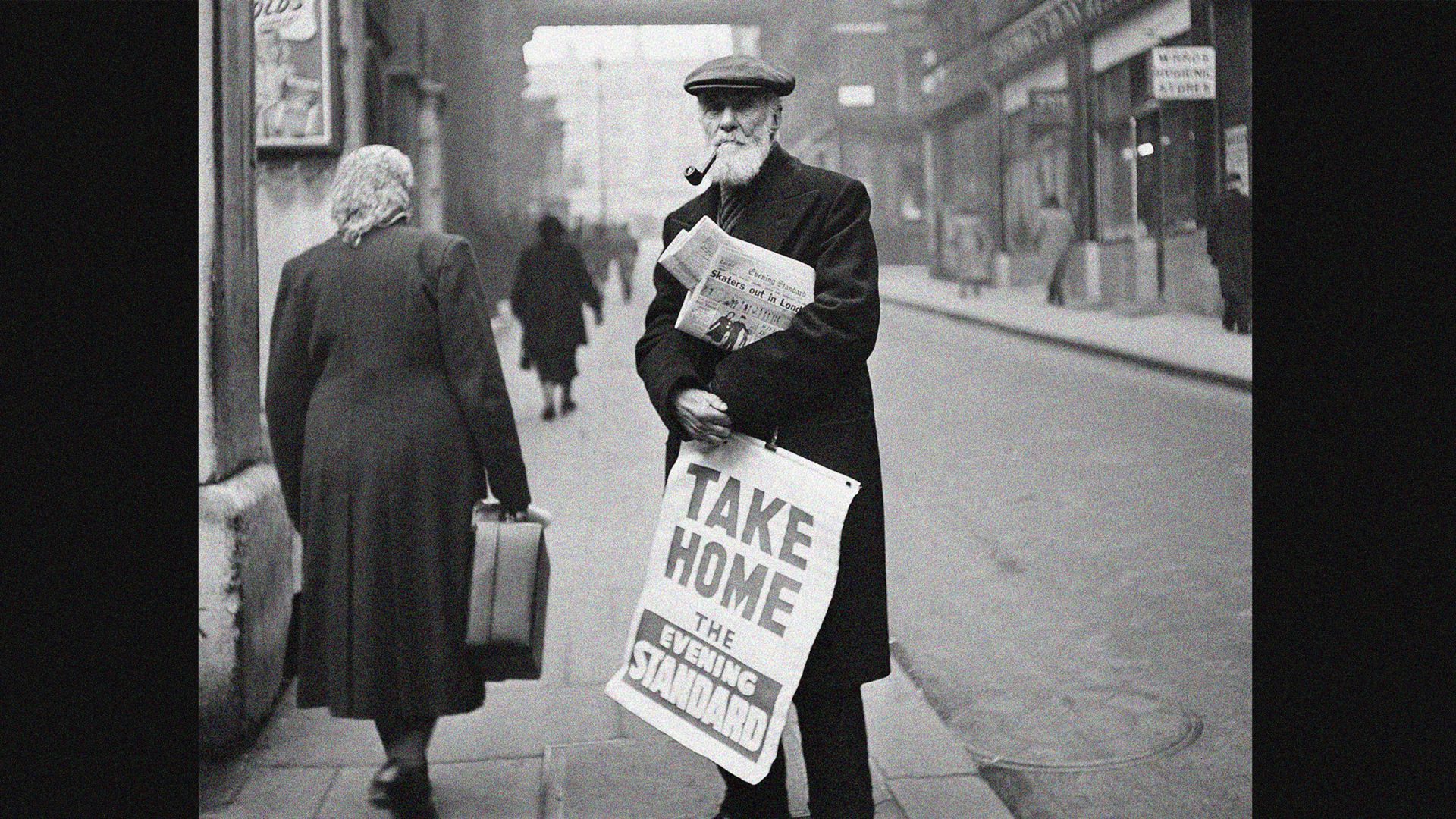

At its zenith, local newspaper publishing was every bit as vibrant as the national sector, and consumers placed huge value on what it provided. In the 1960s heyday, London alone supported two titles, the Evening Standard and the Evening News, which together sold 1.5m copies a day. Eventually, in 1980, the two merged under the Standard banner and then, in 2012, it became a free paper.

By then, it had been bought by the former KGB agent Alexander Lebedev, photographs of whose son, Evgeny, often featured in its pages. Although the younger Lebedev collected a peerage from Boris Johnson, the paper failed to thrive.

It is now reduced to a weekly appearance in newsprint, which is more concerned with restaurants and festivals than the activities of the Greater London Authority, let alone any borough councils. Its online presence offers a mix of celebrity gossip and some national and international headlines, but little else.

Read more: How to kill a newspaper

Online publishing is the inevitable direction for many news publications, and that does not necessarily mean that the content has to become entirely vacuous – but the omens are not encouraging. At a national and international level, those people who are interested and have adequate resources will always have access to accurate and informative news, and while more and more will be online, a print option is likely to persist for some time. The Economist, for instance, shows no sign of giving up its printed edition any time soon.

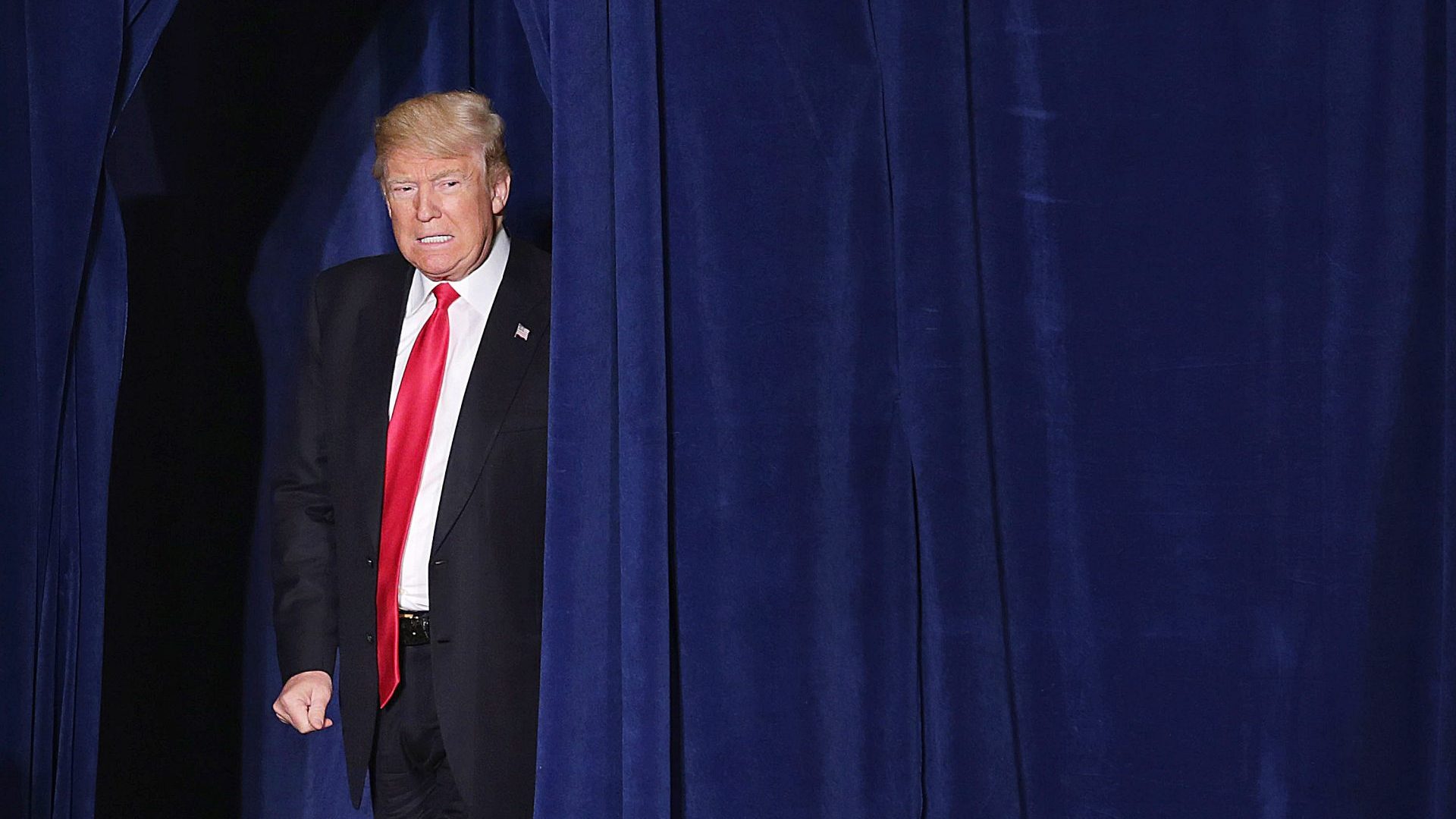

The UK’s national newspapers continue to go through drastic upheavals, with the Observer moving into the ownership of Tortoise, the self-styled advocate of “slow-publishing”, which has previously not seen the need for a printed version. The Telegraph is still in limbo as the government tries to decide how best to intervene in the battle over its ownership.

But at a local level, the printed newspaper has already largely vanished. According to the Media Reform Coalition, by 2023 more than 2.5 million UK citizens lived in local authority areas without a single local newspaper. Another 9 million people were in the precarious position of being served by just one.

Without strong local journalism, local politics is rarely properly reported nor politicians held to account; the views of local people are unlikely to be adequately voiced to the authorities; a forum for curated public debate vanishes – and the combination of these amounts to a significant dilution in the strength of a community.

Citizen journalists can do a valuable job, perhaps covering the occasional council meeting or local planning issue, but it will never compensate for the service provided by trained journalists with an informed overview and access to crucial sources. And the risk is that, in this context, as in most others, the online discourse can be taken over by those with a particular point of view and quickly become a megaphone for prejudice and unsubstantiated rumour.

This tendency is certainly not restricted to local news coverage alone. It would be naive to argue that the UK’s national news media has consistently been an exemplar of accurate, independent reporting.

Political positioning has always been in evidence to a greater or lesser extent – and the former certainly seems to be the case at the moment. The online versions tend to exaggerate the positioning, and reader comments multiply that.

This becomes increasingly concerning as traditional physical newspaper sales shrink. According to Enders Analysis, specialists in the media sector, paid national newspaper circulation in the UK had shrunk from more than 8m in January 2012 to below 3m by May this year.

There are, though, other sources of national and international news available beyond the challenged traditional publishing sector. In particular, the BBC provides news reporting that, while it will always elicit criticism from one quarter or another – and often all four – provides an invaluable service. In large parts of the world, the BBC’s World Service is the only trusted source of information available.

The challenges facing the BBC cannot be over-estimated: satisfying, let alone pleasing, a hugely diverse audience is difficult; doing so when facing enormous financial pressures is almost impossible. Another bout of haggling with ministers is imminent in the looming Charter Review, and at a time when government spending is under crippling constraints, broadcasting cannot expect a generous settlement.

It is not, however, under the threat of extinction that is now becoming a reality in parts of the local news reporting landscape. The BBC’s regional coverage, though, may face a tougher regime and the support that it currently gives to local news providers through what is known as the Local Democracy Scheme is unlikely to gain the additional funding it needs.

Even if that extra support were to be forthcoming, it may be too late to resuscitate the local media that is already demonstrably fading faster than newsprint. Democracy will be the loser.