What would you do if the price of a pint of beer rose to £25? The short answer is: drink less beer. And though, even in these inflationary times, such a price spike is unfeasible, that is exactly what has happened to the price of money.

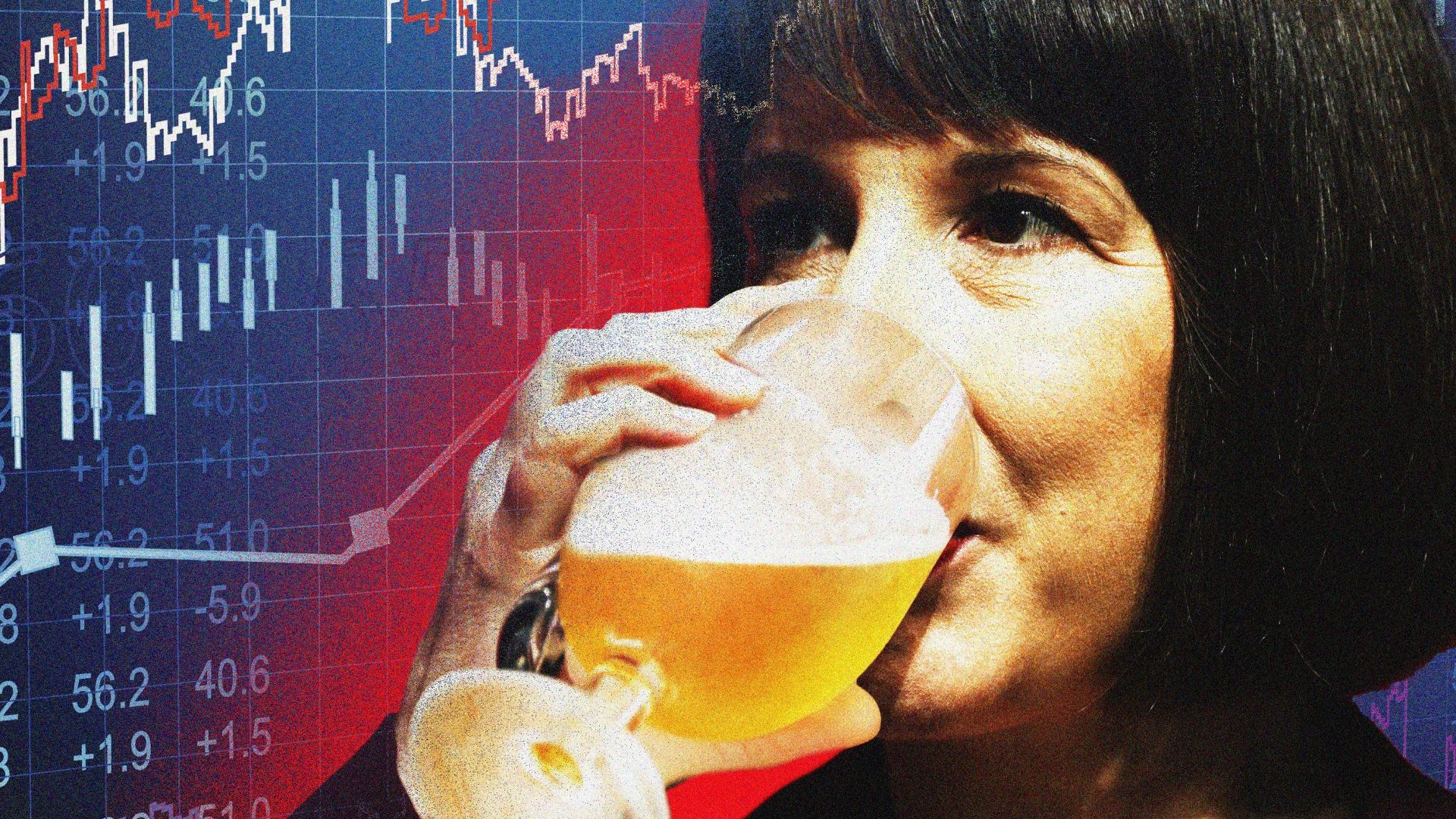

When Rachel Reeves became shadow chancellor, in May 2021, the yield on a 10-year government bond was below 1%; today it is 4.57% – with the 30-year bond yield above 5%. The facts changed and, like John Maynard Keynes she changed her mind, slashing Labour’s commitments to fund green energy investment through borrowing.

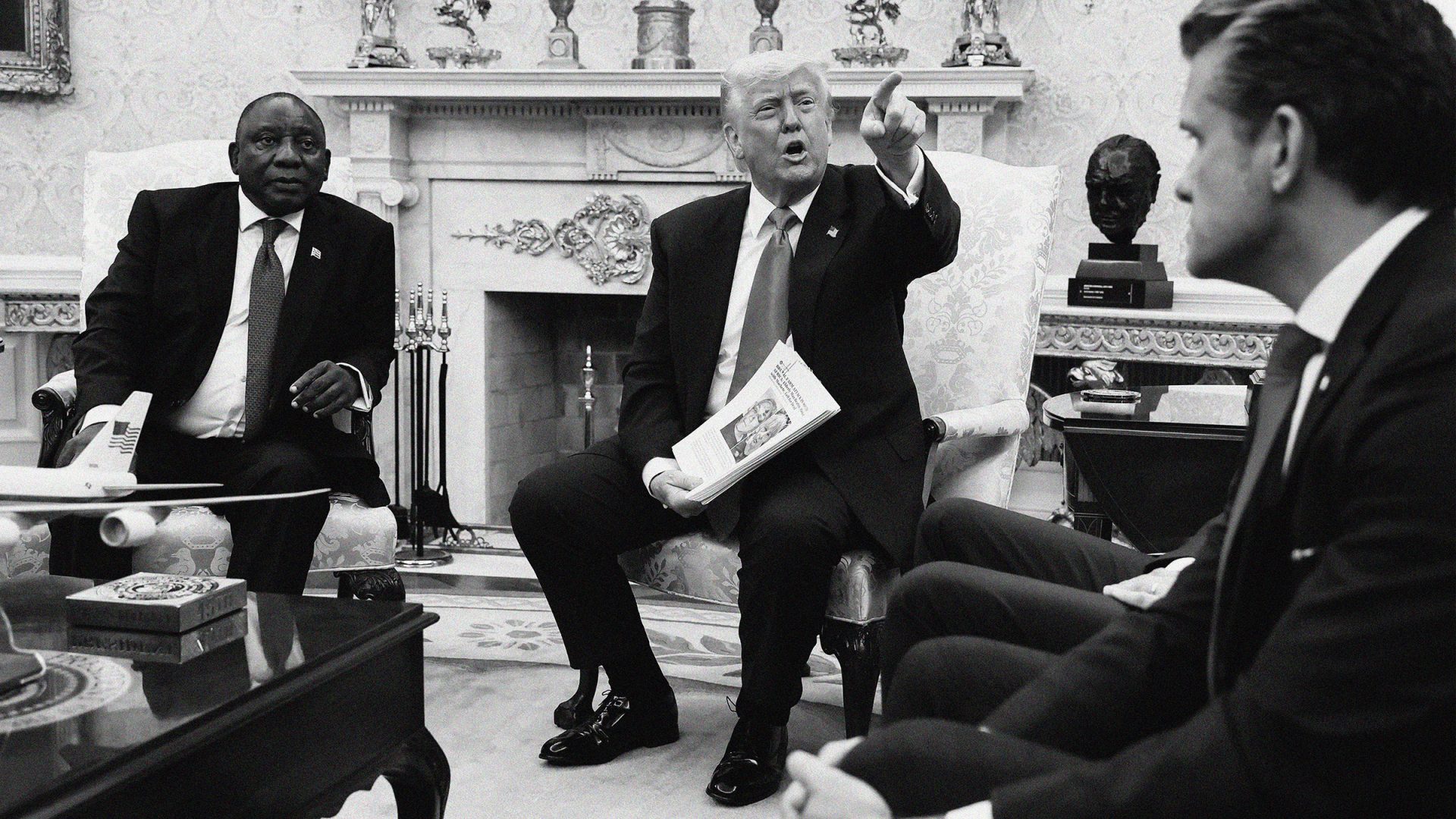

Now, the facts are changing once again. Last week the US Treasury saw demand for its bonds suddenly weaken – as buyers worried about Donald Trump’s four trillion dollar package of tax cuts. In Japan, meanwhile, the interest charged on its long-term debts has surged – a development that threatens to pull billions of dollars worth of Japanese investments out of the USA.

The bond yield is the effective interest rate a government pays when it borrows money – and holding such bonds is supposed to be the safest thing investors can do with their cash. So this massive surge in the cost of government borrowing has a knock on effect on the cost of capital across the economy, constraining both government and private investment.

Though some of the UK’s rising bond yield is the legacy of Liz Truss’s 49 days of madness, we are no longer alone. Fundamentally it reflects the mixture of economic and geopolitical instability in the world created by the invasion of Ukraine and the deglobalisation of trade.

Suggested Reading

Rachel Reeves may have to U-turn on non-doms

We have, in short, moved from an era of cheap money to one of expensive money. And though that is good news for savers, it is bad news for capitalism. It is a signal that those who manage our savings believe they will need to be protected against permanently higher inflation, which governments are incentivised to let rip to erode their debts, and against future defaults – if the tariff war destabilises the finance system.

Nobody in any government, including the USA’s, can know whether Donald Trump intends to crash the world economy as the price of reducing America’s reliance on imports, or whether he is only kidding. Nor can anyone know whether Vladimir Putin, on the morrow of a peace deal with Ukraine, will invade somewhere else, or whether Xi Jin Ping will make good his threats to seize Taiwan.

Yet most ordinary voters cannot see the danger. All they can do is feel its effects, in the constrained ability of the government to borrow in order to fix hospitals, mend roads or build new railway infrastructure.

Most ordinary punters can be forgiven for their ignorance – because the bond market does not make headline news. But political parties cannot be forgiven. The bond market has been described as a “300lb gorilla” that can smash the plans of any government. Yet large parts of the UK political scene just want to ignore the problem.

The prime culprit is Reform. Nigel Farage has promised to end income tax on salaries under £20k, to cut corporation tax from 25% to 15%, and to slash inheritance tax. The cost, according to the Tories, would be in excess of £140bn a year – which would require massive spending cuts or massive borrowing at sky high interest rates.

The Office for Budget Responsibility expects Britain to spend £105bn on debt interest this year – that’s £1 for every £12 collected in tax. Farage’s promises would add to that total massively.

But though they have rightly slammed Reform’s unmeetable promises, which read like a Christmas present list for the economically illiterate, the main parties themselves are refusing to face up to the hard choices in a world where the cost of borrowing has quintupled.

Britain’s growth is anaemic because business investment has flatlined since Brexit, and because neither government nor the private sector is prepared to pump prime through borrowing.

As a result, something has to give. Rachel Reeves is faced with the unenviable choice of having to raise taxes, cut spending, break her own fiscal rules or change them. And even if she raises taxes to cover current spending, the scale of investment needed – in defence, energy and infrastructure – means it can only be funded through borrowing long term.

There is an answer – ending the rewind of Quantitative Easing (known as Quantitative Tightening) or getting the Bank of England to adopt something called yield curve control – where a central bank sets a target interest rate for, say, 30-year bonds and then buys up bonds held by the private sector until the interest rate falls.

But that is what Japan was doing to keep its borrowing costs under control, and it no longer seems to be working.

Ultimately, high bond yields are acting like cholesterol in the world’s financial arteries, making it difficult for everyone who wants to invest, innovate and grow. The solution would be a return to predictability and stability – but the most powerful economy in the world is governened by a man committed to boosting instability.

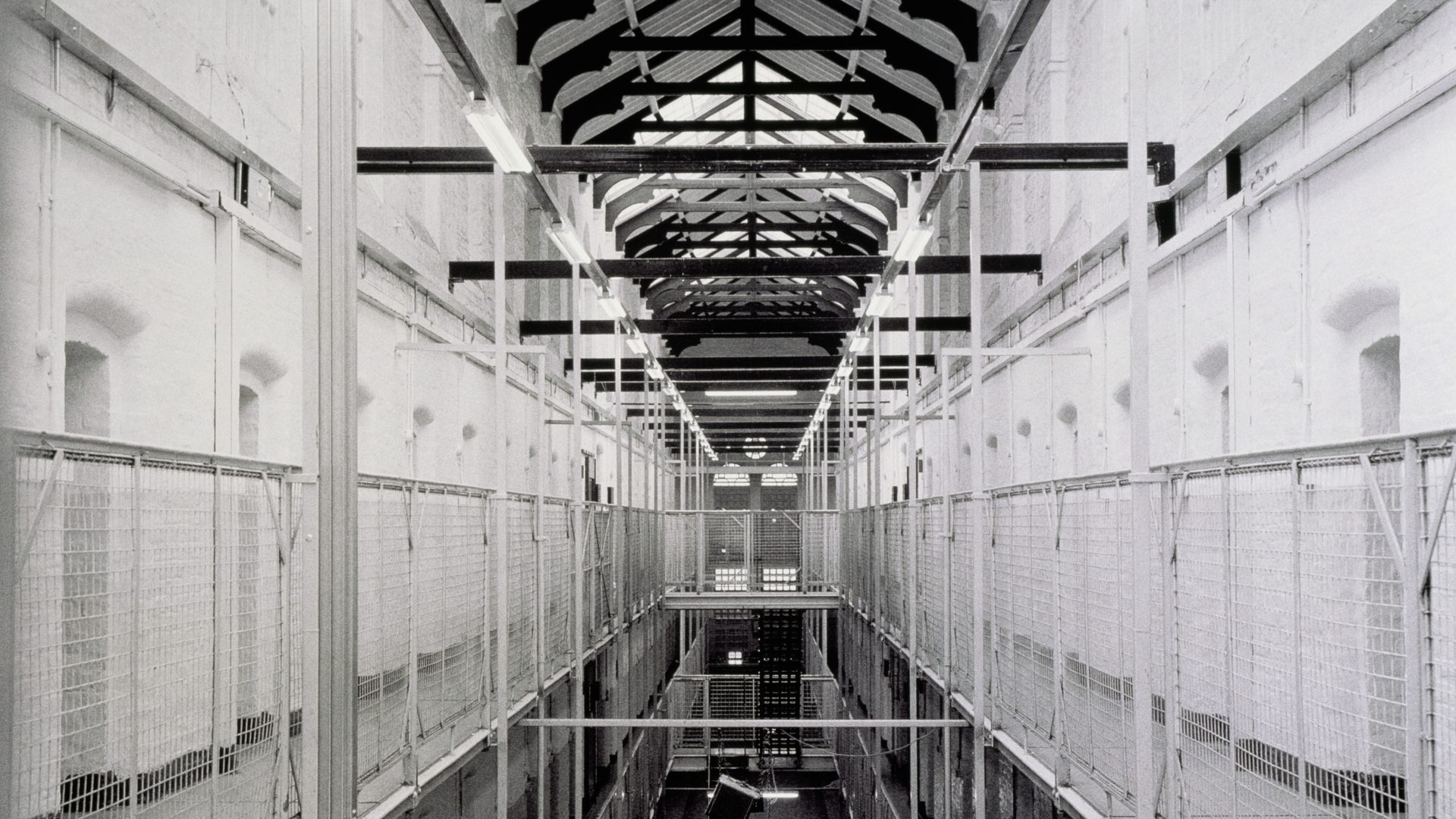

The danger, then, is that at a certain point, more than one major country experiences what the UK did under Truss: a bond-market strike, where investors simply stop buying and central bank efforts to keep the market liquid get overwhelmed.

What happens then? We don’t know, because – as in the Truss fiasco – it is never clear until the morning of Armageddon which institutions are forced into panic selling to meet their own risk management rules.

In the meantime, we need to adapt. Taxing the rich more, taxing wealth, reversing the damage done by Brexit – and not doing the inessential things we got used to during the era of cheap money.

Since savers are now getting 5% interest rates on investments that used to attract less than 1% – maybe Reeves should start by looking there.