What is the difference between a heathen and a pagan? Surely these two English words mean more or less the same thing? Well, the Oxford English Dictionary would support that point of view because, according to the dictionary, a heathen is “a person who does not subscribe to any major or recognised religion – a pagan”. A pagan, on the other hand, is defined in the dictionary as “a person who does not adhere to Christianity, or Judaism, or Islam – a heathen”. It really is difficult to discern a difference there.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, but fascinatingly, it is also rather easy to note links between the two major theories about the etymological origins of these two words.

Pagan has its origin in the post-classical Latin form paganus, whose original meaning was “rural, belonging to a country community, inhabitant of a country community”. The word comes originally from Latin pagus “country district”, which is also the origin of the Modern French words pays “country” and paysage “countryside” as well as Spanish país and paisaje.

The etymology of heathen, on the other hand, is a little more difficult to ascertain. It certainly goes back to Old English hæðen “not Christian or Jewish”, but it probably also merged over time, in bilingual Danelaw areas of northern England, with Old Norse heiðinn “heathen, pagan”, both of which go back to Ancient Germanic haithana which was also the source of Old Saxon hedhin, Old Frisian hethen, Dutch heiden, and German Heiden). But haithana is itself of uncertain origin. One intelligent guess, however, is that it was originally literally “dweller on the heath, a person inhabiting uncultivated land”.

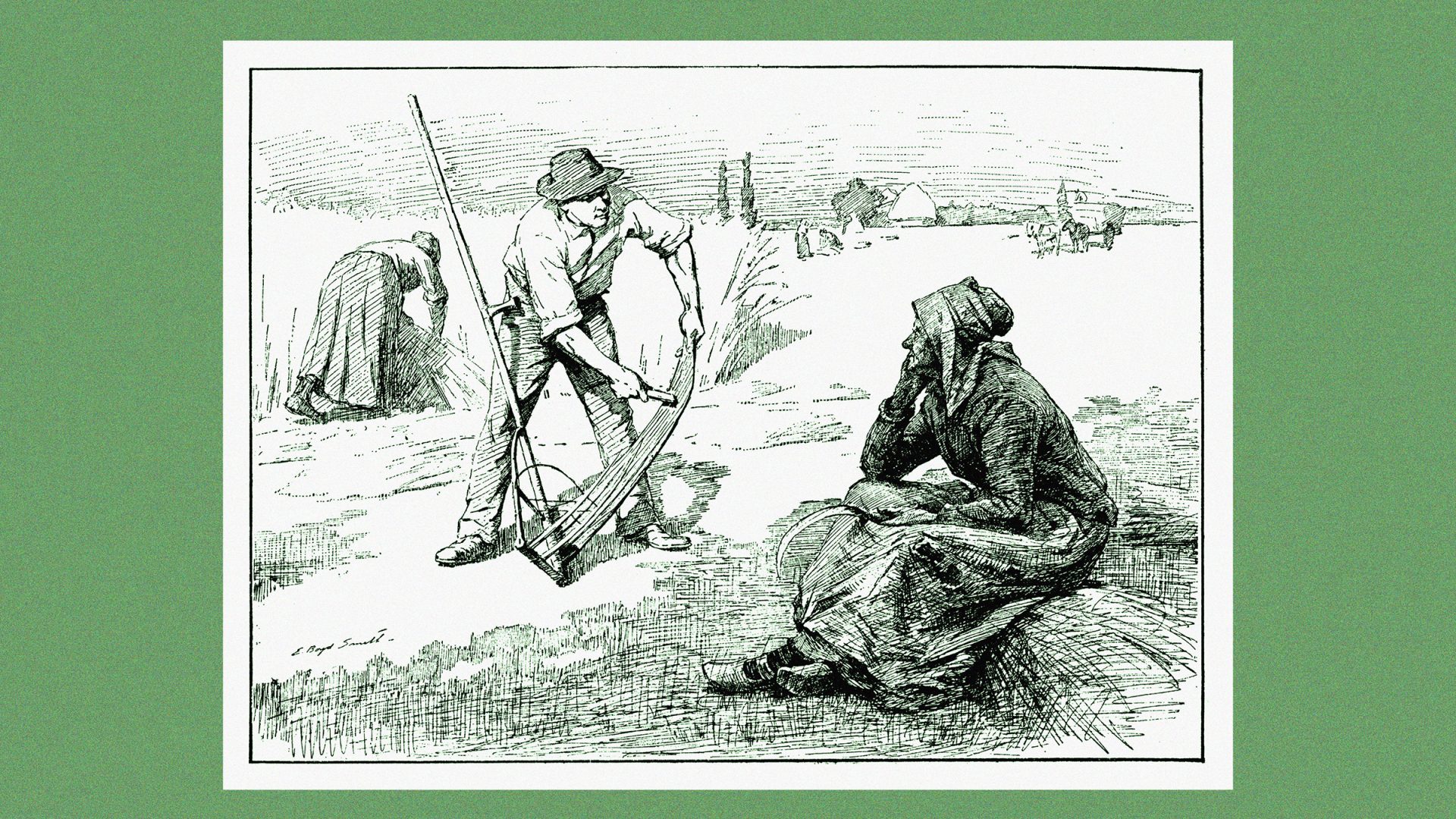

So, from an etymological point of view “heathen” and “pagan” were both terms which were applied to groups of people who were outsiders, country bumpkins, dwellers in rural communities beyond the pale. They were people who did not live within the civilised urban community or, by implication, the Christian religious community. We can interpret this as indicating that, in many areas, paganism lingered on in the countryside well after the more sophisticated urban areas of the Roman empire had been converted to Christianity.

Linguistically, Christianity in the early centuries of its existence was a new religion without a strongly established vocabulary for new and unfamiliar theological concepts or for religious establishments and even edifices. For instance, the etymology of the – at that time – new English word church is rather complex and obscure. It is thought it came from a variant of the Byzantine Greek word kiriakon “(house) of the Lord” which was borrowed into Gothic and then from there into other related languages with forms such as Old Dutch kirika, Old Saxon kirika, Old High German kirihha, and so on. The word seems to have applied initially to a church as a building, but then gradually expanded in meaning to include the Christian church as an institution or organisation.

So it is perfectly possible that Germanic-language-speaking Christians simply found a use for the word haithana “heath-dweller” as the best way of transferring the meanings which were associated with the Latin word paganus “countryside dweller” into their own languages: and in the first translation of the Bible into a Germanic language, Gothic, by Bishop Wulfilas (see TNE 296), Wulfila actually does use haithno “dweller on the heath” as his rendering of the Latin form paganus “pagan”.

LINGER

Today we pronounce the words English and England as if they were written Inglish and Ingland. In the same way, the verb that had originally been “to lenger”, which meant “to stay longer”, has become “to linger” in our modern language.