Many authors, and it tends to be male ones generally, will tell you they have always had a burning passion to write. For as long as they can remember, they tell interviewers or, indeed, anyone who will listen, they have been compelled to pour stories on to the page. They live for writing; cannot remember a time they were not destined to be a novelist. It is a compulsion, they say steepling their fingers and looking wistfully out of the window, it is a calling. They have important things to say and have known it ever since they were able to pick up a pencil and form basic letters.

Others, generally less insufferable, come to writing later, by other routes, and are all the better writers for it.

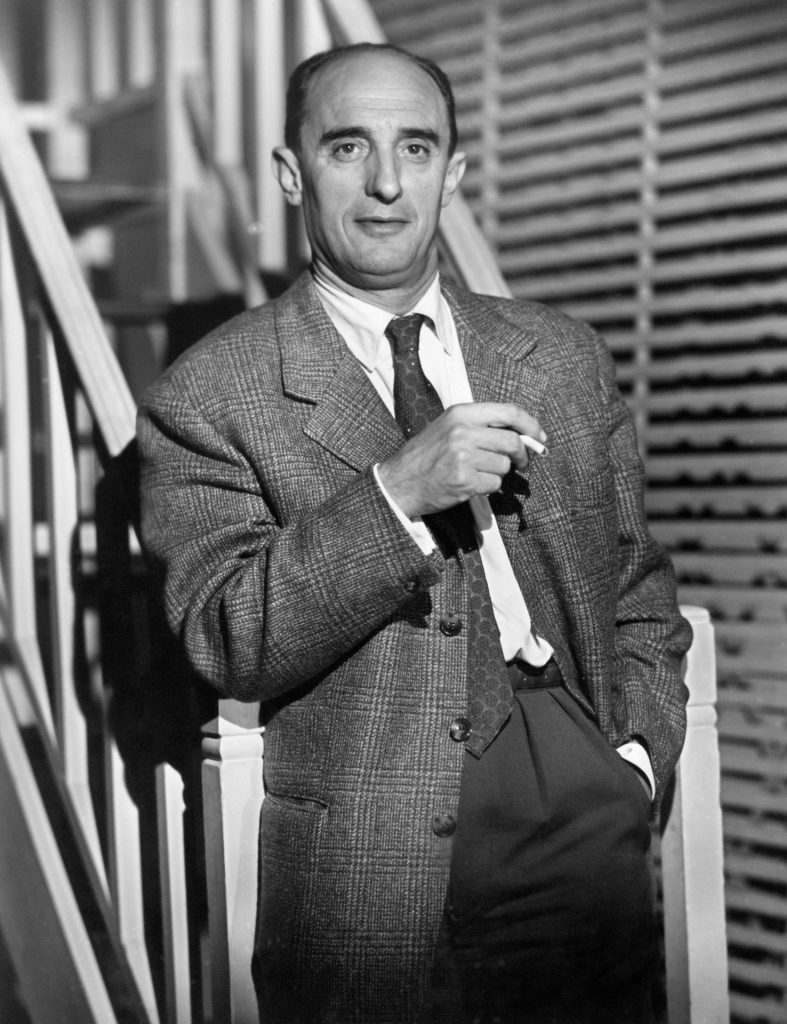

For Pierre Boulle the decision to become a writer was made in his mid-30s just after the second world war, in which the extraordinary circumstances of his participation left him with a psychological void that demanded a new purpose. “This decision to become a writer,” recalled the novelist who died 30 years ago this week, “I took in one hour one sleepless night when the fireflies were dancing.”

If I ask you name all the French novelists you know it is fair to say Pierre Boulle is unlikely to appear anywhere near the top of the list. Indeed, there is a good chance you’ve not heard of him at all. I am fairly certain, however, that you will be aware of his work.

Despite only taking up the pen in his 30s, Boulle published 24 novels, seven collections of short stories and two memoirs. He had a large and dedicated following in France and several of his books were translated into English, selling in decent numbers in the US. Despite this, however, Pierre Boulle was never destined to be a name handed down the generations.

And he was fine with that. For most of his writing career, he lived a quiet and unassuming life sharing a Paris apartment with his widowed sister, spending most days alone with his pipe and old Underwood typewriter. According to those who knew him, Boulle wrote every day of his life from the moment he began his first novel in 1949 until a few months before his death in 1994 at the age of 81.

If Boulle’s name does not ring many bells, two of his novels that transferred to the cinema screen certainly will. After all, The Bridge on the River Kwai and Planet of the Apes rank among the most significant films of the 20th century, both of which were adaptations of books by Pierre Boulle.

Even without his success as a writer, Boulle’s life would still have ranked as pretty extraordinary. He was born in Avignon in 1912, the son of a lawyer who wrote theatre reviews for the local newspaper, and the daughter of the newspaper’s editor. After graduating from the Sorbonne in Paris and the Ecole Supérieure d’Electricité he seemed destined for a successful career as an electrical engineer until, on a whim in 1938 at the age of 26, he took up a job as a supervisor on a British-owned rubber plantation just outside Kuala Lumpur in what is now Malaysia.

When war broke out less than a year after his arrival in south-east Asia, Boulle immediately joined the French army based in the region, then after the fall of France transferred to de Gaulle’s Free French resistance based in Singapore. He received training in espionage and sabotage at a secret establishment known as The Convent where “serious gentlemen taught us the art of blowing up a bridge, attaching explosives to the side of a ship, derailing a train, as well as that of despatching to the next world as silently as possible”.

The novice rubber plantation supervisor was now a novice spy, travelling throughout the region from China to Vietnam organising resistance activities against the Japanese as Peter John Rule, an Englishman whose accent, not exactly home counties RP, was explained away by a fake backstory of being raised in Kuala Lumpur.

In 1943 Boulle received orders to make his way to Hanoi, which he attempted by floating down the Mekong river on a bamboo raft. Captured en route by soldiers apparently loyal to the Vichy regime, Boulle gambled on admitting he was from the Free French in the hope that he might be among friends. Within hours he found himself sentenced to life in prison with hard labour.

Eighteen months later, with an Allied victory almost assured, Boulle managed to abscond from prison with the help of some sympathetic gendarmes, after which he was sent briefly to Calcutta by the British Special Operations Executive before, with the war finally over, being demobbed and making his way back to the rubber plantation.

It did not take long before Boulle became restless. His wartime activities had given him a sense of purpose he had never experienced before, sparking a transformation deep within that he could never quite define but knew that a life growing rubber would never satisfy. During the war he had seen and done things, often terrible things, that made attempting to pick up his previous life as if nothing had happened ridiculous.

Then came that authorial epiphany among the fireflies. He returned to France, rented a room in Montparnasse, set up his typewriter on the dining table and hoped that putting words on to the page would help him process events that seemed even more unworldly when recalled from the distance of Paris. Either way, he was now a writer, “having taken the ridiculous vow to undertake nothing else ever again and having calculated, after selling everything I possessed, that I could live like this for two years restricting myself to bare essentials”.

His first novel, William Conrad, the wartime story of a German spy sent to Britain and titled in homage to his literary hero Joseph Conrad, was published in 1950 but it was his third, 1952’s The Bridge on the River Kwai, that turned out to be his breakthrough. Not least when five years later it was adapted for the screen by David Lean.

It surprises many to learn that The Bridge on the River Kwai with its portrait of that quintessentially British internal struggle between stubbornness and dignity was written by a Frenchman, but Boulle had seen enough Colonel Nicholsons in south-east Asia to create the utterly convincing product of the English officer class that won the best actor Oscar for Alec Guinness.

One significant difference between novel and film is in the fate of the eponymous bridge. In Boulle’s original it is not blown up, rather it remains standing as a monument to Nicholson’s intransigence.

“For three years I fought them over this change,” Boulle recalled later, “but in the end I gave up. These days I don’t bother. I just take the money and shrug.”

For Planet of the Apes, published in France in 1963, the inspiration came not from his wartime experiences but a visit to the Paris Zoo. Standing in front of the gorilla pen, Boulle noted how the animals’ facial features and expressions were distinctly human in nature and the idea of a role-reversed planet was planted in his mind.

The novel was much more overtly a satire in the style of Gulliver’s Travels than the film version starring Charlton Heston that spawned a decades-long franchise. “I don’t consider it one of my best novels,” said Boulle. “For me, it was just a pleasant fantasy.”

The book focuses on a young couple on their honeymoon in space who find a message in a bottle containing a manuscript by a French journalist detailing his experiences on a distant planet where apes are more evolved than humans. Crucially, the book does not feature the film’s climax in which Charlton Heston discovers the half-buried Statue of Liberty, confirming that he has travelled not to a distant planet but a future Earth all but destroyed in a nuclear holocaust.

Boulle did not approve of what became one of cinema’s most enduring images. The Statue of Liberty scene, he felt, turned the story into a specifically American one when his intention for Planet of the Apes was to create a borderless story of humanity as a whole. Ambivalent about the adaptation, he declined an invitation to the premiere on the grounds he had to help his niece with her homework.

By then he had already been commissioned to write a sequel but, almost to his relief, the script he submitted was turned down.

“I haven’t seen the second or the third films,” he recalled. “I did read the script for Beneath the Planet of the Apes but it doesn’t interest me because it’s no longer my work. I am incapable of working as part of a group of people, which I know is necessary for making a film. When I write, I am alone. I give the book to my editor and I do not want to change a thing, not even a comma.”

Ultimately Boulle was happiest in his own head, where he was answerable only to himself and the vow he’d made that sultry night after the most tumultuous period of his life.

He had seen the worst of humanity up close and almost everything he wrote after that was an attempt to make sense of it. The biggest danger to the world was the banality of evil and Boulle knew that whatever steps the human race took to advance their civilisation a descent into self-defeating savagery was inevitable.

Humanity would never change, but he had to try even if all he had was his typewriter and the stories in his head, the clatter of the keys sounding deep into the Parisian night, the stars over Montparnasse replacing the fireflies.