His name is a byword for depraved, deviant, dangerous sex. As the Marquis de Sade himself proclaimed: “Sex without pain is like food without taste.”

So to stage an exhibition based on the life and works of a man who took part in orgies of rape and torture and boasted he had written the “most impure tale that has ever been told” could be criticised for adding to the undeserved legend of a monster, or for indulging in cheap sensationalism. Sade: Freedom or Evil at Barcelona’s Centre for Contemporary Culture (CCCB) avoids that trap. Just about.

Instead, its curators weave a narrative through a panoply of outrageous behaviour, terrifyingly explicit videos, pitiless imagery of violence against women, not to mention the improbable (but voluntary) use of a leak by a naked transexual, to discuss the balance between sexual freedom – even sexual excess – and its role in understanding the moral imperatives which drive society in the 21st century.

As co-curator Antonio Monegal explains: “We want to introduce a different moral perspective from the 21st century, which focuses not just on the freedom part of Sade’s thinking, but on the evil that comes with it. Is he still relevant today and in what way?”

The show is divided into six sections which range from a scene-setting prologue, Sade and his Philosophy in the Boudoir, to some of the wilder shores of transgression and perversion before considering the connection that unbridled freedom can have on crime and politics.

But, first, what about the man? Does he deserve the fame – or the notoriety – he has inspired?

The Marquis de Sade was born in Paris in 1740 and died in December 1814. In 1763, after a military career, he married the daughter of a high-ranking bourgeois family and had two sons. Within months of his marriage, he was arrested for harassing a prostitute and kept under surveillance by police for his disreputable behaviour.

His debauchery remained unchecked. He imprisoned a female beggar and tortured her by whipping her and dripping hot wax on her back. She reported him to the police but was paid to drop the charges. On another occasion, he enticed five young females and one man to a château in the south of France where he kept them imprisoned and subjected them to six weeks of ugly ignominy. Then, after an orgy in Marseille, four prostitutes fell ill after eating a chocolate-coated aphrodisiac.

By now De Sade had been found guilty of sodomy, an offence punishable by death, and only an intercession by his wealthy mother-in-law to King Louis XVI saved him. Instead, from 1777, he spent 13 years in prison where he wrote feverishly – political and philosophical tracts and many of his best-known works including his litany of lust, “his impure tale”, One Hundred and Twenty Days of Sodom. They were too shocking for general consumption and found only in the pornographic collections of the wealthy. A sort of 19th-century dark web.

His reputation remained in obscurity, unacknowledged even by his own, thoroughly embarrassed, family, until in 1909 the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire hailed Sade as the “freest spirit that ever lived”.

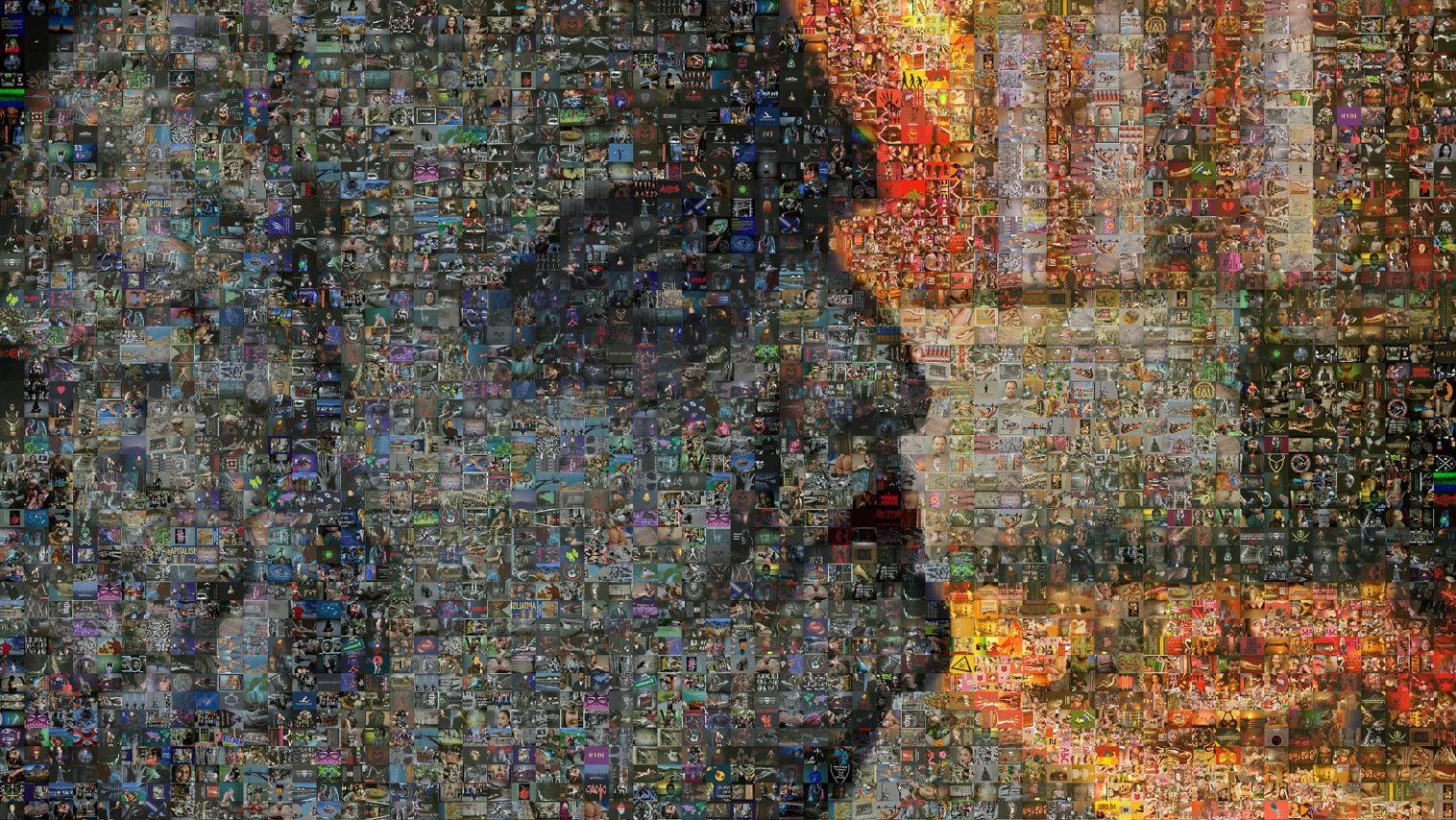

Just how that free spirit and the possible influence it might have on society today can be gleaned from the witty Googlegrama: Sade by Barcelona photographer Joan Fontcuberta who took Man Ray’s 1938 Imaginary Portrait of the Marquis de Sade and overlayed a mosaic of 6,000-plus tiny images taken from the internet. By inputting words such as sadism, desire, pleasure, capitalism, hedonism and evil he created a visual lexicon of everything Sade stands for. Less subtle is the video shadow show by Chinese-American Paul Chan, Sade for Sade’s Sake, which is a parade of frenzied group sex that lasts for more than five hours.

Scenes from Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom by the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini are central to the concept of the exhibition. It tells of four libertines who abduct teenage boys and girls for an orgy rather as Sade himself had done but this is not a paean of praise to Sade or to transgressive behaviour but an attack on the fascism of a consumer society in which the freedom to satisfy every desire can end in darkness and evil.

By the time the film was made in 1975, the avant-garde movements of the 20th century had discovered in Sade a spokesman for freedom. How that freedom was expressed is revealed in Transgressive Passions – an exhausting array of splayed limbs and threatening penises.

As one might expect from Otto Dix’s dystopian vision of the world, Lustmord (literally “lust murder”) is a pitiless etching of female victims of a frenzied attack. Rudimentary scribbles by Alberto Giacometti include one of a man garrotting a woman, and crude – in every way – cartoony drawings by Roberto Matta portray prodigiously endowed men in scenes of violent arousal. Rape, violation, mostly (im)pure male fantasy is the message here.

It comes almost as a relief to come across a happening, 120 minutes dedicated to the Divine Marquis, made in 1966 by French surrealist Jean-Jacques Lebel – a jamboree of nudity and sex with Lebel smeared in excrement, wearing a blue wig and a priest’s chasuble, spraying a naked performer with Chantilly cream.

It was symptomatic of the thirst for liberation and bold self-expression which characterised much of the 60s art world and a generation still coming to terms with the legacy of the second world war. After Auschwitz, the argument went, how could anyone be offended by such sexual shenanigans, or indeed by the transsexual with the leak?

The happening was deemed shocking enough for Lebel to be imprisoned but today it seems sweetly old-fashioned compared with the section labelled Perverse Passions. Here, there are no limits to freedom – as long as the participants are consenting.

Pierre Molinier (1965) dresses up in fetishistic bondage gear, presenting his buttocks to the world and posing in Éperon d’amour, (spur of love) with a penis emerging from his boot. Robert Mapplethorpe’s sophisticated but unvarnished representations of gay sex compete for attention with a terrifying series by photographer Carles Santos Ventura, which includes one of a naked woman holding a huge nail about to penetrate an upturned man and another involving an unclothed couple, a violin bow and what looks like a giant fish hook. Not for the faint hearted.

American Andres Serrano endured death threats for perceived blasphemy when Piss Christ was first shown in 1987 in which he placed a plastic crucifix in a glass tank of his own urine. In Heaven and Hell, a woman streaked with blood, hands tied above her head, is shackled alongside a smirking cardinal.

The most challenging display involves a group of sadomasochistic performers which is covered off from the gallery with a warning that viewers might find the work “distressing”. Hot wax and blood-letting is involved.

But this is between consenting adults. That’s their freedom.

But what are the limits of that freedom? What is socially considered acceptable and when does that tip over into evil? Sections on criminal and political passions investigate the connection between the dark side of human nature and the consequences of unbridled freedom.

The German psychiatrist Richard Kraft Ebbing, whose 1886 Psychopathia Sexualis was one of the first books to discuss homosexuality and bisexuality, argued that the mental state of sex criminals should be considered when judging crimes.

It’s a theory that could be applied to the Moors Murderer Ian Brady who read Sade’s novel Justine, in which “wickedness is the source of human activity” and might have been inspired by it to write The Gates of Janus while in prison, offering an often terrifying but largely tedious glimpse into the mind of a murderer analysing the minds of other serial killers.

Catalan photographer Laia Abril examines where that wickedness can lead. In her sensitive series On Rape: And Institutional Failure (2019) she relates the testimony of victims of violence and misogyny, touchingly illustrated in one case with a beautiful wedding dress worn by a woman from Kyrgyzstan who was forced to marry a man who “ravished” her.

She is also showing a triptych of hundreds of faces of Catholic priests from across the world who have been accused, prosecuted and convicted of sexual assault and rape. The faces are blurred; the message is clear.

In the section Political Passions, Mexican artist Teresa Margolles has collated more than 300 covers of the newspaper PM in a display which runs along one entire wall of the gallery. Each cover has the same formula; an account of a gruesome killing alongside a glamour model. Sex and violence – the ideal mix for its readers.

These are striking works which expose evil with considerable skill and empathy and it is perhaps significant that they are by women, whereas the sections on transgressions and perversions are concerned more with the lust for freedom and the freedom to lust. Furthermore, the majority of these works are by men. And for men?

This draws a volley of “no, no, no” from curator Monegal, who points out that the exhibition co-curator Alyce Mahon is the author of The Marquis de Sade and the Avant-Garde and that several female writers have come to Sade’s defence. The academic Camille Paglia wrote that “no education in the western tradition is complete without Sade” while in her 1979 book The Sadeian Woman, Angela Carter argued that he was a “moral pornographer” who argued for “rights of free sexuality for women, and in installing women as beings of power in his imaginary worlds.”

Simone de Beauvoir wrote an essay Must We Burn Sade? in 1949 in which she described him as a “great moralist” though that was a judgment much hedged in with ifs and buts.

Feminist activist Andrea Dworkin, however, insisted his fiction defended the male desire to “possess” women and, indeed, this is what Sade himself had to say: “When I have so corrupted this fragile thing and brought out a writhing, mewling, bucking, wanton whore for my enjoyment and pleasure… at that moment she is never more beautiful to me.”

So the question implied by the exhibition – Freedom or Evil – remains unanswered. On one hand, it would not make sense to attribute all the evils of humanity to Sade but on the other, his writing and behaviour can, perhaps, help understand what evil means.

Maybe he should have the last word: “All universal moral principles are idle fancies.”

Sade: Freedom or Evil. CCCB, Barcelona to October 15