Rejoice! The UK government is on track for “the largest expansion since the Victorians” in one crucial area of infrastructure. Could that be schools for social carers, perhaps, or roads, or maybe, at last, some new reservoirs? No, the proud boast made to parliament last Thursday relates to prison places.

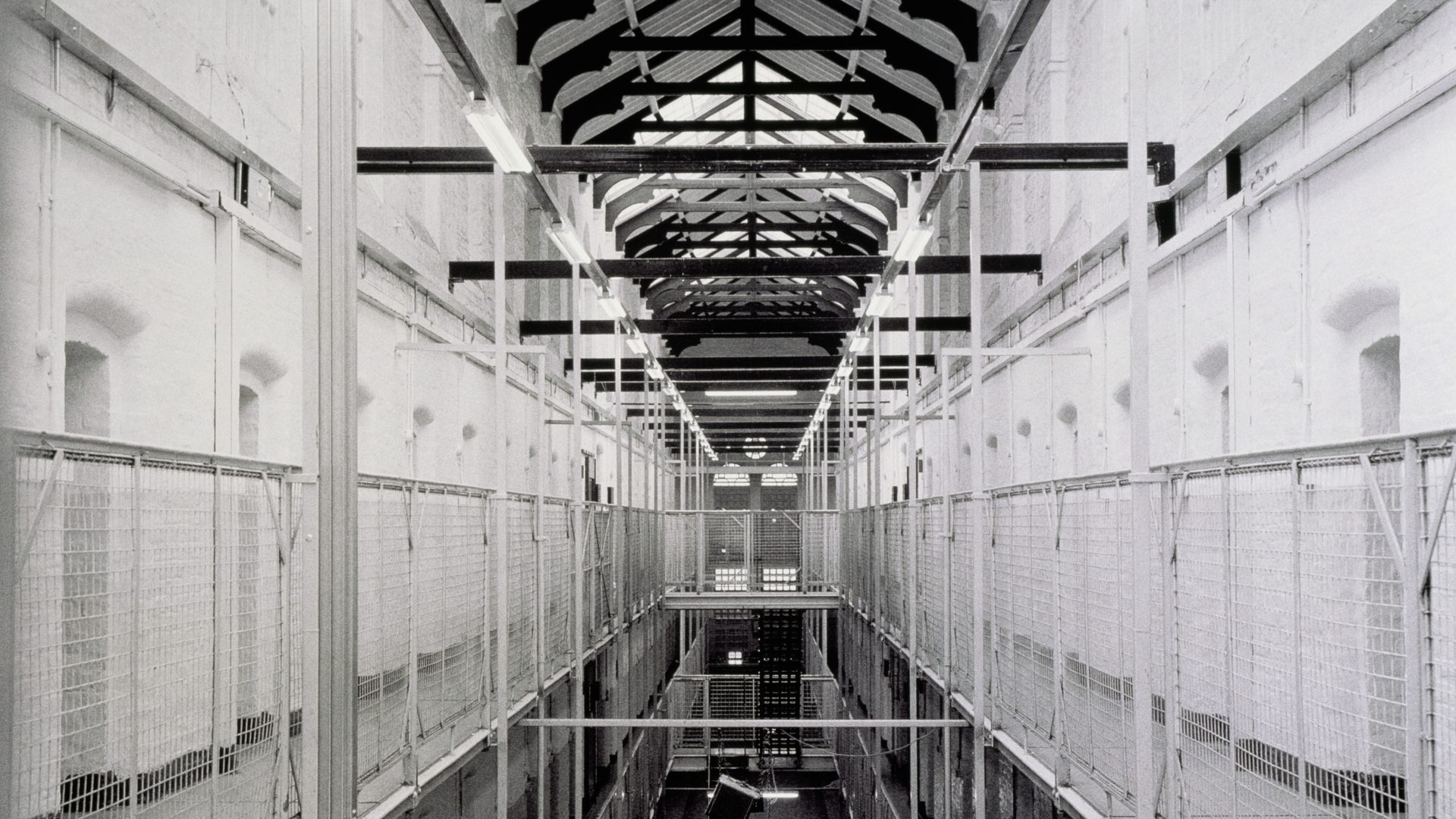

Superficially, this could hardly be more dispiriting for those like me who believe that the country already jails far too many people. The justice secretary herself went on to admit that “our prisons too often create better criminals, not better citizens”. But the country’s penchant for locking up offenders has landed this government with a massive problem: a constantly growing demand for places in institutions, many of which are unfit for purpose and some of which are unfit for habitation of any kind.

It appears Keir Starmer wants to radically reshape prison policy. His appointment of James, now Lord, Timpson as prisons minister indicated a determination to bring real reform. Asking David Gauke to lead a review of sentencing policy was another pragmatic step in that direction: Gauke is a former Tory justice minister who was sacked from the party, and then from parliament, because of his lack of support for Boris Johnson’s Brexit strategy.

Gauke’s report advocating more use of non-custodial sentences and a greater emphasis on dealing with the underlying problems of offenders – a high proportion of whom have addiction issues, poor levels of literacy and multiple difficulties with housing, relationships and general health – accompanied the statement by Shabana Mahmood, the justice secretary.

The official launch was pre-empted by a flurry of media excitement about “chemical castration” for sex offenders. This is a gross exaggeration of the use of medication that the report moots as a possibility, and was guaranteed to upset social liberals. Yet some cynics might suggest that the government would have been happy with that outcome.

When the then home secretary, Michael Howard, declared in 1993 that “prison works”, heads across the UK nodded in agreement, many adding a wish to “throw away the key”. Their views have not changed, even though it is now clear that crime can thrive even inside some prisons, where drugs proliferate and those who enter without a habit are at risk of picking one up.

Punishment rather than rehabilitation is the demand from many voters. Any liberal thinker who doubts that should take note of the polling on capital punishment. In January this year, More in Common found that 55% of people wanted to bring back the ultimate sanction for crimes such as multiple murder and terrorism, up from 50% a couple of years earlier. Among millennials, (those born between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s) the proportion in favour was 58%. Only 27% were opposed.

Even if the government had once been prepared to take a principled stand on issues such as prisons, the local election results, with the massive victories for Reform, will have reminded it that it cannot risk alienating a significant proportion of the electorate.

“Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime” was the slogan first used by Tony Blair when, as shadow home secretary, he addressed the Labour conference in the year that Howard made his (in)famous remark. Blair was acknowledging the voters’ appetite for harsh punishment – Starmer knows he must do the same.

But the crisis point that is now being reached in the UK’s prisons provides an opportunity to make changes while blaming impossible inherited circumstances.

Sentencing guidelines that pander to the public and the more strident media have led to a record number of people being crowded into a limited prison estate. This has had disastrous effects, not least on any hope of rehabilitation, as facilities and staff for training and education are overwhelmed.

More from this author

The flawed Assisted Dying bill still deserves to succeed

The government has already had to institute one batch of early releases in order to avoid a potential complete breakdown in the system, when there would simply have been nowhere left to send even the most dangerous criminals.

Now, despite another 2,400 places being added, if current trends continue, by early 2028 the country will be short of 9,500 prison places. This is why the government has accepted Gauke’s recommendation that most prison sentences should offer the chance of earlier release, on licence and with strict conditions, than is currently the case. There will also be a move towards much greater use of non-custodial sentences for offences that currently put people behind bars for less than a year, often with disastrous long-term effects.

These sentences do not work on any level: nearly 60% of those sentenced to 12 months or less reoffend within a year. And, while women make up only a tiny proportion of the prison population, there will be a determined effort to further reduce the number.

Achieving a more humane, successful and economic prison system will take time. These may seem like baby steps to prison reform, but they are a start. Crucially, they are enough to unsettle the extreme “throw away the key” brigade without alienating the bulk of the electorate.