When Russia invaded Ukraine, it started a war of attrition with the rest of the world. The resulting global economic crisis has seen higher oil and gas prices push every cost index higher, spelling misery for millions already battered by inflation caused by the post-Covid demand surge.

Now, as the war drags on and Russia continues to weaponise its fuel exports, dependent governments are scrabbling around for alternative supplies in case Moscow turns off the taps in retaliation for sanctions.

The crisis is particularly acute in Europe, which relies heavily on Russian gas, but the inflationary fallout is being felt everywhere. In the UK, which gets around 4% of its gas from Russia as well as 9% of its oil and 27% of its coal, electricity and fuel prices have pushed inflation to above 10%, with the Bank of England predicting 13% by October. That’s when the energy price cap is due to rise again, potentially pushing the average household bill above £3,300 a year. Some desperate consumers are threatening to simply stop paying their bills, with thousands signing up to a campaign called Don’t Pay UK.

But in the longer term, this energy crisis could have a silver lining if governments decide to respond by investing heavily in clean energy. Long before Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, the transition to cleaner energy had been gathering pace, with new capacity for generating electricity from renewables, such as solar, wind and hydropower, increasing to a record level worldwide in 2021, according to the International Energy Agency.

But the transformation hasn’t been fast enough and the world is still on course for potentially catastrophic climate breakdown because of greenhouse gas emissions. Now the war has added energy security to the list of dire consequences of inaction, and this has particular relevance in Europe. It relies on Russia for 40% of its gas, around 27% of its imported oil and 45% of its coal, and European governments have been forced to acknowledge that Russian fossil fuels are no longer affordable – in financial, ethical, or planetary terms.

Lord Adair Turner, chair of the Energy Transitions Commission, an international think tank, said Europe had already ratcheted up its climate ambitions before the war – notably by adopting a Green Deal meant to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and cut emissions by at least 55% by 2030 – but it had expected to use natural gas as a bridge towards a renewable future.

The war has changed that calculus: Russia has limited flows through its Nord Stream 1 pipeline, sparking fears of a supply shock in the depths of winter. Several EU countries have said they may have to use coal-fired power plants to plug immediate gaps, but a commission official insisted such moves would be temporary and the shift to clean energy was still on course.

Despite the short-term turmoil, the war and Russia’s weaponisation of its energy supplies could yet reinvigorate the push for renewables. “This has enabled Europe to realise what is possible and get its skates on,” Turner said. “There has been an appreciable upping of ambition of where we want to be in 2030, but what has changed really significantly is the willingness to say we have to address things like bottlenecks and the constraints that stop us getting there fast enough.”

In March, the EU said it would cut its dependency on Russian gas by two-thirds this year and end its reliance on Russian supplies well before 2030. To do this, it drafted REPowerEU, an ambitious €210bn (£178bn) plan to “speed-charge” the Green Deal, as European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said at the May launch of the blueprint.

Under the plan, renewable energy should make up 45% of the EU’s energy needs by 2030 – up from around 22% in 2020. To achieve that target, the approval process for wind and solar farms will be accelerated, ending bureaucratic delays that can sometimes stall projects for up to nine years. REPowerEU also calls for solar panels on all commercial buildings by 2026 and on residential buildings by 2029.

Alfonso Medinilla, head of climate action and green transition at the ECDPM think tank, notes a historic precedent: it was during the Opec oil crisis in the 1970s that the world saw the earliest developments in renewable energy infrastructure. That crisis ended too soon for the change to be durable, but this time, he is encouraged by the measures included in the EU’s green roadmap.

“REPowerEU is very much framed as a security issue and this opens the door for measures that before were quite difficult to take,” he says, singling out the front-loading of infrastructure investment and efforts to simplify the approval process.

However, change cannot happen overnight and Brussels is also looking to import liquefied natural gas (LNG) from other sources, including the US, Norway, Qatar and Algeria, among others. This has angered environmentalists, with Greenpeace saying this means more money for energy giants such as Saudi Aramco and Shell. A report by the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) research institute warned that the rush to build new gas infrastructure around the world would either lock the world into “irreversible warming”, or create a mass of stranded assets.

The EU’s climate policy chief, Frans Timmermans, insists the commitment to renewables is solid, but he admits a level of dependency on gas and describes the switch as possible but “bloody hard”. “We have to be transparent, we have to be honest: we have a short-term serious problem because of the Russian [imports] that… cannot be replaced immediately by renewables. So we will have to go out there in the world and try to find alternatives to Russian gas,” he said at the launch of REPowerEU.

Sarah Brown, senior analyst at the Ember think tank, says the commission is making the right noises even if the timelines to end dependency on Russian fuels may be ambitious. “Public opinion has massively turned so governments aren’t frightened of saying domestic renewables are the answer,” she said. “The argument that renewables are less reliable, that’s blown out the window. Any argument that they could possibly be more expensive has been blown out the window. The argument that fossil fuels offer security of supply? Gone.”

A June study by Ember and the Centre for Research and Clean Air found that the energy and Covid crises had spurred Europe’s green transition. Of the EU’s 27 member countries, 17 have improved their plans to increase renewable energy since 2020 and, if achieved, these plans would see 63% of EU electricity produced from renewables by 2030, up from 55% under their 2019 policies.

The war in Ukraine is unlikely to change the direction of travel. Two months after the war started, the US special envoy on climate change, John Kerry, told a conference that it was time to accelerate the transition to a clean energy future, partly because Putin “cannot control the power of the wind or the sun”.

In another positive sign, in August the US Senate approved what could be the largest US climate legislation in history, with $369bn (£305bn) in climate and energy provisions, including tax credits for clean energy development and electric cars, and a $27bn (£22bn) fund to advance renewable technologies. Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer said it was “the boldest clean energy package in American history”.

Switching to renewables is to some degree pushing on an open door, given how rapidly costs have come down – around 80% in the last decade alone – and the fact that soaring oil and gas prices mean renewables are economically more viable. But some countries will find it easier than others.

In Portugal, the government wants to raise the share of renewables in power generation from 58% now to around 80% by 2026, with the aim of being carbon neutral by 2050. It helps that there is a lot of sunshine and strong winds available on Europe’s western coast and that the country has also become something of an innovator, boasting the world’s largest floating solar park in a hydro dam.

The project on the Alqueva reservoir – western Europe’s largest artificial lake – consists of 12,000 solar panels covering an area the size of four soccer pitches. Run by the country’s main utility company, EDP, the project combines two kinds of renewable energy – hydro and solar – to maximise the output from both in a process called hybridisation.

“It means that you can double or triple the energy you can export in the same line very quickly so it’s a way to go fast on the decarbonisation pathway and reduce dependency on other energy and fossil resources,” said Miguel Patena, group director in charge of the project, which started producing energy in July.

For Patena, the war in Ukraine means the transition to clean energy is now inevitable. “For us at EDP there was no turning back before and now there is an increasing level of urgency,” he told the New European. “The war in Ukraine showed we need to be independent, or as independent as possible, and made people aware that we all have to make an effort.”

Next door in Spain, wind power produces around 23% of its energy, with solar accounting for just under 10% and nuclear providing around 20%. Last December, the Spanish government said it would invest €6.9bn (£5.9bn) in renewables, green hydrogen and energy storage over the next two years, and hoped to attract another €9.45bn (£8bn) in private funding.

Like Portugal, Spain has abundant sun and wind and is also committed to pushing green hydrogen, a zero-carbon fuel made by using renewable power to split water into hydrogen and oxygen molecules. REPowerEU includes a hydrogen accelerator plan, which aims to see Europe produce 10m tonnes of green hydrogen and import 10m more by 2030. At the moment, Europe produces 98% of its hydrogen from natural gas, including gas from Russia, and Sarah Brown notes that green hydrogen is not “a golden bullet” and will not be online until the late 2020s at the earliest.

Germany finds itself in a tricky situation as Russian gas accounted for 55% of its imports before the war in Ukraine. Now, Europe’s largest economy is looking to source LNG from Australia, Qatar and the US while also committing to speed up its transition so that renewables account for 80% of its electricity supply by 2030 and 100% by 2035.

After the war started, there was speculation that Germany might extend the lifespan of its nuclear plants – the last three are due to close this year – but some officials have ruled this out, with economy minister Robert Habeck saying it would only save about 2% of gas use. But the debate goes on. The government has also said it will rapidly build two new LNG terminals for imports, as it diversifies its supply from Russia. It won’t happen overnight – Germany expects to be largely reliant on Russia for gas until the middle of 2024.

A further complication for Germany is that around half of its homes use natural gas for heating so there is a need for a huge electrification project, which will take time, money and a skilled workforce. The government has said it will invest €200bn (£170bn) on measures such as subsidising rooftop solar installations while regulators plan to auction off more wind power concessions.

Italy, which imports around 40% of its gas from Russia, is looking to increase gas imports from Algeria and Angola, and is working on incentives for offshore wind farms. In a bid to cut demand, it has also decreed that air conditioning must be limited to 25C in public buildings this summer.

France stands out in Europe because it relies on nuclear power for around 70% of its electricity. President Emmanuel Macron wants to build at least six new reactors and a fleet of smaller plants, although he is also planning a tenfold increase in solar power capacity by 2050 and 50 more offshore wind farms.

The role of nuclear in Europe’s energy transition is controversial; not everyone is convinced it is truly green. The European parliament recently voted in favour of including nuclear and gas in the EU’s sustainable finance taxonomy – designed to steer investment to low-carbon projects – despite some opposition from lawmakers and environmentalists.

Critics also note that it can take decades to build nuclear plants, with their lifespan limited to around 40 years, although work is being done to extend that. Then there’s the question of safety, which was brought into sharp relief when Russian soldiers seized the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine. The question of how to safely and sustainably dispose of radioactive waste remains unresolved.

Supporters of nuclear power point to the creation of small modular reactors that could be quicker and cheaper to bring online. However, Russia produces around 35% of the enriched uranium needed in the world’s reactors. So this is not a straight win for energy security either.

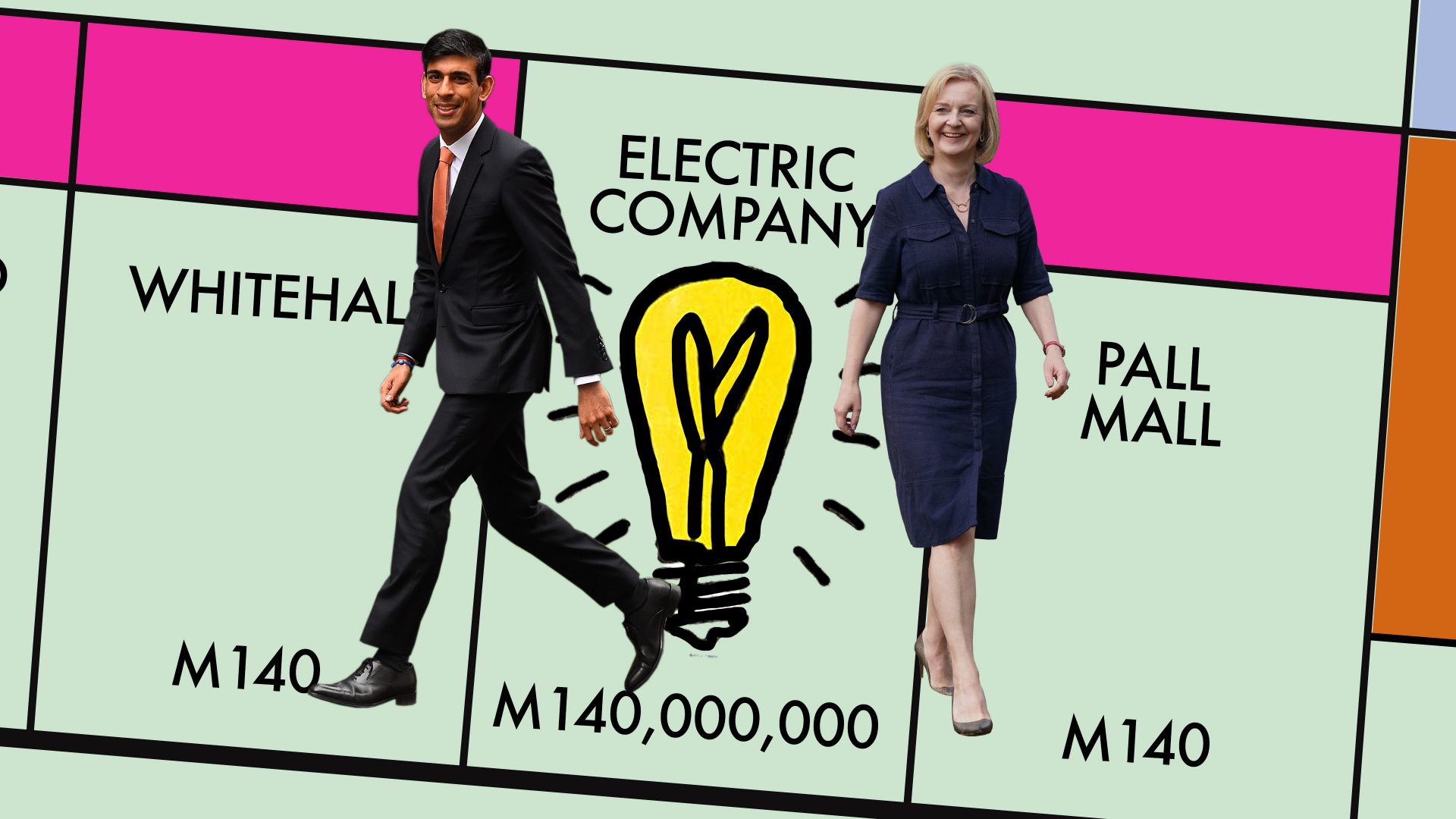

The UK – where likely new PM Liz Truss seems to have come out as a solar panel sceptic – also sees a significant role for nuclear in its transition to cleaner energy. The Energy Security Strategy, published in April, aims to deliver up to eight reactors by 2030. Nuclear power provides around 15% of Britain’s energy and the government wants to raise capacity from 7 gigawatts to 24GW by 2050 so that nuclear power accounts for a quarter of UK electricity. But decommissioning old plants will cost taxpayers millions.

Lord Turner said there was no doubt the core of the UK electricity system by 2050 would be offshore wind, but there was also room for nuclear.

“We think where you’ve got nuclear you should run it for as long as you possibly can, and that we should put effort into engineering to extend the life of nuclear plants,” he said.

Energy efficiency is also a big issue as Britain has some of the leakiest houses in Europe. Environmentalists want the government to do much more to support households to insulate their homes and install heat pumps.

Even if the tide is turning, there are constraints. Increased demand can cause its own problems, with analysts warning of shortages in raw materials, including steel for wind turbines, and Covid-related disruption to supply chains in China, a key supplier of solar panels. This year’s drought has also affected hydropower and nuclear facilities, which are cooled using river water, from China to Europe, raising questions about how to factor the vagaries of climate change into the global energy outlook.

For Turner, the legacy of the war in Ukraine may be the deglobalisation of energy supply, with countries relying more on domestic sources and prioritising political stability and security when sourcing from elsewhere. For Europe, this could lead to the development of closer energy ties with Africa. “We’re just going to see that thinking about energy security being a much more overt part of strategies in future,” he said.