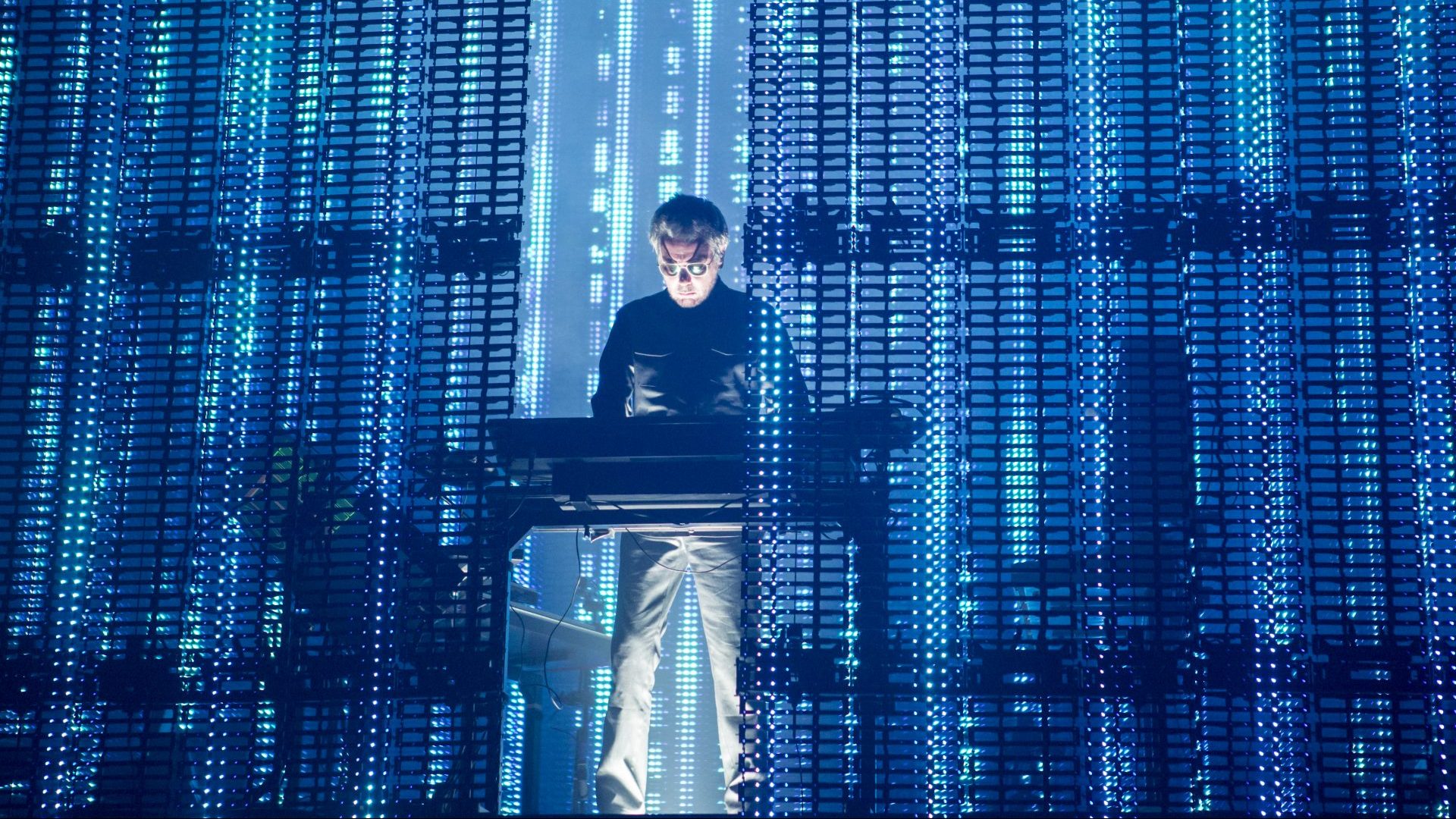

What are you doing on Christmas Day? While the rest of us are struggling in the kitchen or slumped on the sofa, Jean-Michel Jarre will be in the Château de Versailles’ hall of mirrors, staging a unique hybrid performance in front of a live audience and simultaneously via the metaverse through virtual reality.

It is almost de rigueur for the electronic music innovator whose lavish shows featuring huge laser displays and projections began with a free performance for a million people on Paris’s Champs Élysées on Bastille Day 1979, and have since taken in megagigs at Nasa in Houston and by the Pyramids on Millennium Eve.

At 75, the man who proved so influential with groundbreaking albums such as Oxygène and Équinoxe is still creating using the latest technologies. In Versailles, he will don the LYNX mixed reality headset, allowing a virtual audience to connect with the event through VR, or on tablets and smartphones. His avatar will appear in the centre of a futuristic hall of mirrors, commemorating Versailles’ 400th anniversary – a location that symbolised artistic and technological excellence in the 17th century.

Jarre’s long tradition of embracing the visual arts was marked at last month’s Geneva International Film Festival with a special award for his outstanding contribution to music and the digital arts. But rather than reflect on past glories at Geneva, he instead unveiled another immersive creation. The Eye and I, a virtual reality experience made with Taiwanese artist Hsing-Chien Huang.

He shows no sign of slowing down. November also saw the release of his latest recording, Oxymoreworks, a collaboration with a host of young talent. It’s an extension of 2022’s Oxymore, conceptually his most ambitious and groundbreaking album to date, and the first commercial release of this scale to fully utilise multichannel and binaural sound (spatial 3D).

While Jarre resists the temptation to look to the past, Oxymore saw him pay homage to his mentors, the godfathers of electronic music and giants of musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry. His earliest influences, these were men who embodied his mantra of using technology as a disruptive force.

Oxymore was composed, recorded and produced in 360-degree audio in the “Innovation” studios in the home of musique concrète, Radio France’s Maison de la Radio et de la Musique in Paris. The same studios where Jarre first started experimenting with sounds at the start of his career with the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète under the instruction of its founder, Schaeffer.

Talking about Schaeffer and Henry, Jarre says: “They were really the pioneers of a new language, a language which became, and [still] is today, a major influence on the way we compose music worldwide.

“They really created the idea that we could do music not only based on notes based on solfeggio, but by mixing noises and sounds in with orchestral sounds, or traditional musical sounds.

“This rather surrealistic idea is coming from these guys in France in the late 1940s. The idea of mixing the sound of a bird with a clarinet or the sound of an engine with percussion.

A kind of surrealistic approach – another French movement. Also, mixing two elements, which are apparently not made to work with each other, to create something new and unexpected. Oxymore is really based on this idea.

“What’s interesting in their approach is the idea of processing sounds, processing noises. They were performing in the late ’40s, with five or six turntables and some 78s, the first vinyl, scratching them and playing them backwards. They were DJing 40 years before DJing started!

“So, it has been, of course, a major influence on me when I was studying over there, but also a major influence on the way we’re doing music these days. Whatever we do, hip hop or techno, electro, or pop or rock.”

Jarre argues every modern artist now uses musique concrète in some way because it was at the very root of sampling. An everyday part of modern musical language. In part, he set out to raise awareness of this rich legacy on Oxymore.

“I thought it was important for me to pay tribute to this period because these people are not necessarily known all over the world. The way we’re doing music these days is directly coming from their work and their exploration in the early 20th century.”

This underlines his belief that electroacoustic or electronic music is very much a European concept – rather than drawing from American jazz, rock or blues traditions. Instead, he says, its origins lie in pioneers such as Stockhausen in Germany, Henry and Schaeffer in France, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in London and Leon Theremin in Russia.

Its origins, he posits, likely stem from Europe’s classical music heritage, making such electronic works better suited to less structured, longer-form pieces rather than the three-minute pop format.

Oxymore has a more personal link with Henry. Jarre had planned to work with his former mentor, but his death in 2017 meant their collaboration never happened. Henry’s widow though gave Jarre some stems and samples her husband had intended for him, and while only 5% of the final album contains this material directly, Jarre says the inspiration he drew from his maestro’s work provided the spine of the project.

There is another connection with Henry in the use of spatial audio on Oxymore.

“I wanted to create the first album conceived and composed in 360, in spatial audio,” he says. “It was also another link with Pierre Henry, who was the first one in the late ’40s to explore spatialisation in a rather primitive way. Of course, what we can do today because of modern technology is a step ahead.”

Oxymoreworks was always intended to be an expansion of its parent record, rather than new compositions. He explains the rationale behind his choice of collaborators, all drawn from a wide range of electronic genres.

“I thought it could be interesting and exciting to contact some artists I like, and maybe that I could see fitting the project, to ask them to create an extension to Oxymore and, in their own way, to pay tribute to these foundations of electronic music.

“You have so many different artists, established artists such as Brian Eno, Martin Gore [Depeche Mode] and Armin van Buuren, and also emerging artists.

“Some French artists also because of the French link, and also some female artists because it’s also very important to enhance the idea that in the history of electronic music you have a lot of very important female artists. From Suzanne Ciani, Éliane Radigue and Delia Derbyshire, and then more recently, some young artists, the British artist Adiescar Chase on the album, Nina Kraviz, the Russian DJ, and Irène Drésel, a very, very interesting French female composer.

“I really let the artists do whatever they have done. It’s very refreshing to see a project you’re carrying for quite a while suddenly being approached with kind of a fresh look. It’s always very enriching. It’s a constant learning process. It’s exciting.”

Jarre does not subscribe to the theory that older artists had things better in their day. With the technology available, Jarre contends this is one of the most exciting times to make music.

“I think young artists and beginners are very lucky to live in these times. It’s important to recognise that, because we never realise how important the present time is for an artist. Lots of times you are driven by a kind of nostalgia, saying yesterday was better, tomorrow is going to be worse.

“At the moment, we have so many opportunities with the emergence of AI and immersive worlds. There are great opportunities for musicians, because when we’re talking about immersion and immersive worlds, everybody’s talking about the visuals, but actually the most important sense for human beings when we’re talking about immersion are your ears, not your eyes.

“The visual field is 140 degrees, where the audio field is 360 degrees. So, we can see that music and musicians and sounds are really more than ever at the centre of these new modes of expressions.”

He believes that in the same way electronic music changed culture in the 1960s and 70s, new technologies possess the same power of disruption.

“Moments of disruption are always great opportunities for artists. Everything interesting in any kind of art form is coming from accidents, from twisting the system, from creating your own way of dealing with present times.

“And I think after Covid, what’s going on now… I mean, the dark times we’re going through, are also, in a sense, as dark as it can be, also opportunities to create, to react and to give birth to new mode of expression.

“If we stay in the technological world, we know technology dictates styles and not the reverse. It’s because we invented the violin that Vivaldi did the music he did. It’s because we invented the camera that we have Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, Fellini. And not the reverse.

“These new instruments we have these days are going to create the times, the different art forms and new art forms in the future. Beyond music.”

Oxymore too has a visual extension in the metaverse. Oxyville is a virtual Music City, an open space in which Jarre hopes DJs or young artists will create and exchange ideas.

The Eye and I, meanwhile, came from his and Hsing-Chien Huang’s shared fascination with the notion of surveillance with its influence and presence throughout the ages.

Their immersive work invites participants on an interactive journey through the evolution of surveillance, from religious supervision to today’s digital omnipresence and control. Through 12 cells set in a panopticon, visitors explore the influence of surveillance in art, family, politics, social organisation and technology. Jarre’s exclusive music composition enhances the immersive experience, creating a singular collaborative work for the mind and senses.

Jarre added: “If the Lumière brothers were alive today, they would be creating in the metaverse. More than an artistic encounter, The Eye and I is a unique opportunity for immersive creation, addressing the theme of surveillance and control in the form of a digital entertainment accessible to all.”

His fascination for creativity using the latest tools available shows no sign of dissipating, extending also to a collaboration with Renault to develop unique new sounds for the car manufacturer’s future electric vehicles.

“I don’t have a deliberate plan,” he says simply. “My driving force is just curiosity. Since I was a teenager, what makes me explore one field or the other is actually curiosity. And as long as your body is carrying you and you keep your curiosity fresh, it’s a kind of timeless activity, writing music or doing movies.

“You have different kinds of artists. I remember when I was 25, or 30, some of my colleagues were already very scared about innovation, very scared about the future.

“I’m not like that. I’m not judging anybody. But I’m not particularly interested in what I’ve done. I’m much more interested with what I’m going to do, what are the possibilities around me. What are the tools I can use to be in phase with the society of my time? This, in my opinion, is the core business of any artist.”

Jean-Michel Jarre’s Oxymoreworks and Oxymore are both available now. His Versailles 400 show will be broadcast online via his YouTube channel, and in virtual reality on the French VRROOM platform on December 25. Further info: www.chateauversailles-spectacles.fr