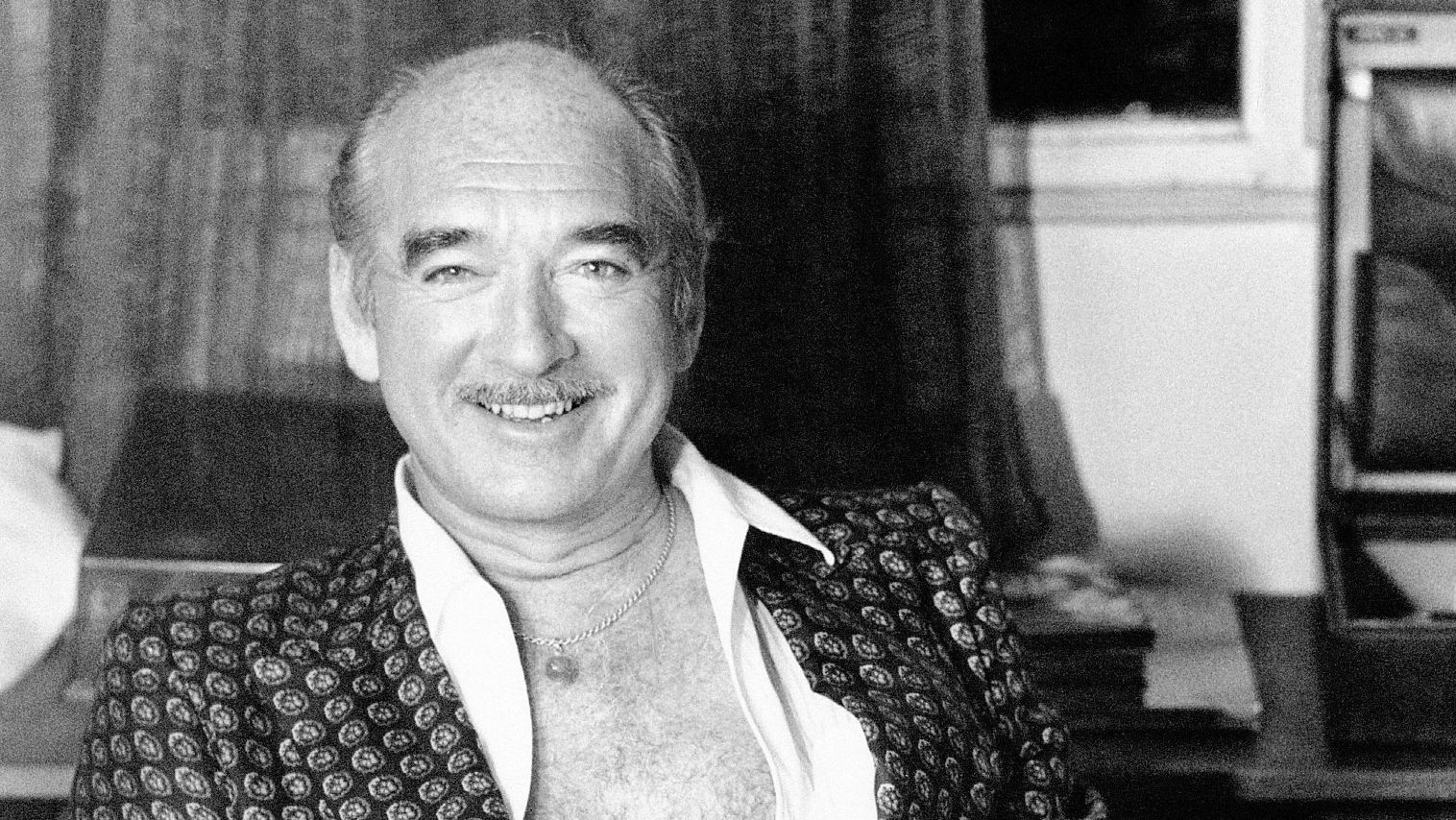

“Pleasure is a profession to be learned,” said Eddie Barclay, and he could have done a PhD in it. Dressed in white and prowling St Tropez like a panther, he was the musician and composer who became an innovative producer, promoter and record company executive, and then became a legendary socialite. He was Quincy Jones, Brian Epstein and Truman Capote rolled into one.

According to one rival, Barclay not only “invented showbiz” but “industrialised the profession”. In the studio, he worked with Jones, Django Reinhardt, Jacques Brel, Charles Aznavour and Juliette Gréco. At his lavish homes in Paris and on the Côte d’Azur, he partied with Brigitte Bardot, Jack Nicholson, Barbra Streisand, Elton John and Alain Delon.

He married nine times, and frequently told an anecdote whose British equivalent is George Best’s “where did it all go wrong?” It was when he arrived at Neuilly’s Hôtel de Ville for his sixth wedding and the celebrant greeted him with “what a pleasure to see you yet again”.

But for Eddie Barclay, pleasure had to have a point. “My parties get people talking. They pay me back the money I invested,” he insisted. Vastly wealthy himself – in the mid-1960s he was already earning more than £20m a year – he railed against the idea that he “manufactured” hits and acts for self-publicity, insisting that his cunning promotions were in the name of giving young talent the wealth they deserve.

“I don’t manufacture,” he said. “I put on an exhibition to keep them going because at the start, they have to be able to eat, able to work. Some of those artists now earn between 50 and 100 million.”

Typical of Barclay’s genius was what he knew would be his long-time collaborator Brel’s final album. The Belgian poet/singer-songwriter’s health had been failing for some time and a man who was already notoriously publicity-shy was unwilling to play on his audience’s sympathy. So he delivered Les Marquises to Barclay with strict instructions not to promote the record prior to the mutually agreed release date, November 17, 1977.

Even though Brel was a legend in France, it would not be easy to stoke interest in Les Marquises without industry norms like advance radio play, review copies for the nation’s press and interviews with TV and newspapers. So, Barclay later explained, “we had to turn the secrecy surrounding the record into an event in its own right. This meant letting people know that Les Marquises would be unavailable to EVERYONE before November 17.

“And to prove that we weren’t messing around, I dispatched the albums nationwide in padlocked boxes. An accompanying note advised retailers that the code for the boxes wouldn’t be issued until November 17. So, the big day comes, representatives from my record company got in touch with the retailers and the padlocks were removed.”

The upshot was that Jacques Brel’s last long player sold over 600,000 copies on the day of release alone and more than a million in France overall.

Barclay was born Édouard Ruault in Paris in 1921. The son of a waiter and a postal worker, on the day his parents purchased a bar, Café de la Poste in 1935, he swapped his school uniform for a waiter’s apron.

Working in a place with live music provided Eddie with the perfect platform to develop his interest in the opposite sex and to teach himself how to read music and play the piano. “And then,” as Barclay would remark, “the Nazis rolled into Paris and ruined everything.”

Believing jazz to be a “degenerate art form”, the invaders forced Barclay into his first acts of rebellion, leaving the family home to play the music he loved in basements all over the city. He also changed his name, a decision that would assume a new degree of importance when, with the war over, he opened a nightclub at which he and his second wife Nicole regularly performed.

The couple also launched a record label, Blue Star, to which they signed the American singer and actor Eddie Constantine, while Eddie had side hustles as a songwriter for future client Aznavour and as co-editor of Jazz magazine.

A chance meeting with American jazz aficionado Alan Morrison in 1952 represented Barclay’s next step on the road to success. Sealing a deal to distribute Mercury Records in France, Eddie took great pride in introducing post-war Paris to the music of Ray Charles, Duke Ellington and Jones, the last of whom would blame the notoriously flirtatious Barclay for “infecting me with a love of women”.

His love of American music was repaid when a contact in the US telegraphed him about “the most important discovery since Einstein. A revolutionary, unbreakable record, each side of which can last thirty minutes.” Barclay introduced the microgroove, 33rpm record to France and the money flowed in.

His record label, now boasting his own name and discovering domestic talents like Dalida and Eddy Mitchell, could now secure the giants of French popular music – Johnny Hallyday, Gréco, Aznavour – plus a relationship with Belgian renaissance man Brel that defined both the artist’s and Barclay’s careers. The two weren’t always close, with the poet describing Eddie “a money man” while Barclay complained that “Jacques always wanted more time. Even when the record was recorded, he wanted more time. He always felt there was something he had missed.”

Things became so fractious that, for an entire decade, Brel wouldn’t record anything for Barclay, preferring to concentrate on his acting, directing and poetry careers. If this upset Eddie, he didn’t really show it, spending his days building a mansion in the south of France and looking for more Mrs Barclays.

Young brides were, alas, but one of the defining features of Barclay’s later life. The others included near-constant ill-health, through which he issued defiant statements – he would live to 120, he said – and an autobiography titled The Party Must Go On. Battling throat cancer even while he was nursing Brel through his last recording sessions, Eddie was ultimately undone by a decade of cardiac trouble. Passing away in his beloved Paris in the spring of 2005, the obituaries celebrated Eddie Barclay as a force of nature, a boulevardier who made music and love with equal enthusiasm.

Beneath the charm and the pizazz, Eddie Barclay was as sincere as he was humane. For as he believed that making another record might prolong Jacques Brel’s life, so “Mr Showbiz” took it upon himself to nurse the artist through the recording process, moving him into his home and ensuring that Brel never wanted for anything.

So when Eddie Barclay described the making of Les Marquises as “among the most rewarding experiences of my life”, only the most cold-hearted would assume the rewards he was talking about were financial.