Private Huston S Riley felt the pounding of his heart as the doors of the landing craft lowered, and seconds later he felt the punch of a bullet. He stumbled into the water and for a moment he took in the tableau of noise and confusion that was Omaha beach. And then he was hit again.

Crawling in the surf towards God knows what, as men fired and fell around him, Riley felt himself lifted by unknown hands. He was being carried towards the beach by a fellow serviceman and a man he didn’t recognise.

“I was surprised to see him there,” explained Riley years later. “I saw the guy’s press badge and I thought: ‘What the hell is he doing here?!’ He helped me out of the water and then he took off down the beach for some more photos.”

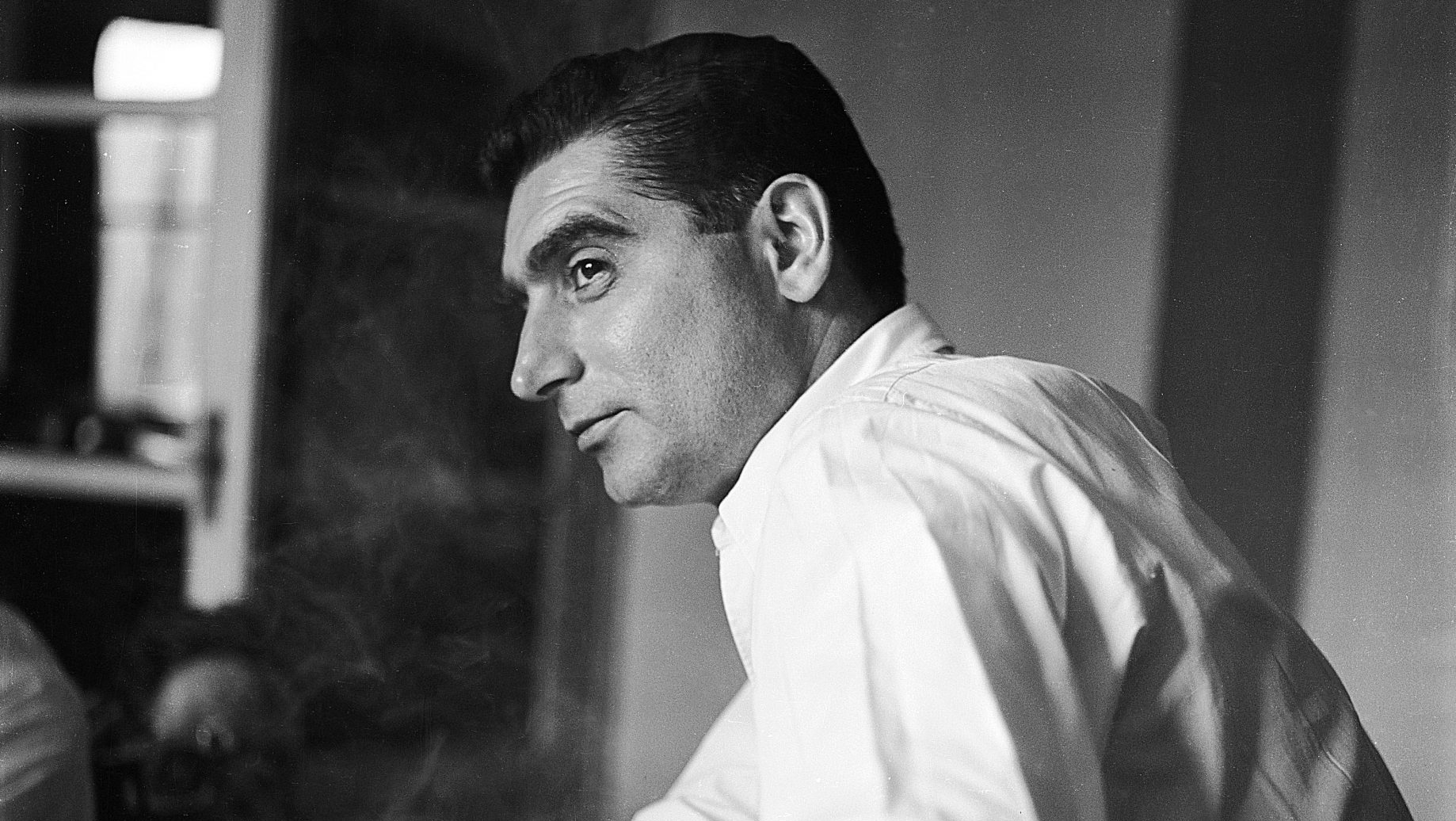

The man was Robert Capa and the picture he took of Hu Riley on D-day will be familiar to anyone with an interest in warfare, photography and/or the human condition in extremis. The Budapest-born Capa once said: “A war photographer’s most fervent wish is for unemployment,” but on June 6, 1944 – the day of days – the Budapest-born Capa had much work on his hands.

Having volunteered to cover the story for Life magazine to ensure there was a photographic record of D-day, Capa was aboard the earliest waves of American craft to land at Omaha beach. With him were two cameras and countless rolls of film.

In total, Capa was on the beach for an hour and a half. During this time, he often found himself working under heavy enemy fire. By the time he returned to sea, he had taken 106 pictures and also participated in the rescue of Huston S Riley.

All Capa’s work that day was nearly lost. Life’s photo editor John G Morris remembered: “Simply getting the film back had been a major undertaking. It meant getting the undeveloped film back across the Channel to London where everything had to be processed and censored… finally, a package arrived on Dean Street from Capa. I ordered the dark room to give me contact prints as soon as possible because we were under terrible deadline pressure. A few minutes later, a lab assistant burst in saying: ‘The films are ruined!’ There was nothing on the first three rolls.”

But the fourth roll? “There were 11 images,” said Norris, “and I ordered all of them to be printed.” These pictures became known as “The Magnificent Eleven”, an invaluable visual record of the Longest Day.

Since the image of Hu Riley was somewhat blurred, the magazine initially focused attention on Capa’s clearest images. Whether the quality of the Riley print was the product of lab error, a faulty camera or Capa’s understandable nerves, it’s this, the photograph’s dynamism that makes it the standout work of a standout career.

And to think, while he was photographing Riley, Capa had his back to enemy gunfire. Little wonder he would have preferred to be unemployed. But given what emerged from his time spent documenting the second world war, the Spanish civil war and the conflict in French Indochina, the civilian’s understanding of warfare would have been hugely diminished had Robert Capa not been so damn good at his job.

Born in what was pre-first world war Austro-Hungary, Robert Capa came into the world as Endre Ernő Friedman, the son of a Romanian father and a Slovakian mum. His left wing views and Jewish ancestry led him to leave Budapest while still in his teens.

Endre landed in Berlin, where he acquired schooling in the art of photography together with vital experience working as a dark-room assistant. By the early 1930s, Friedman was already working for Dephot, a German photographic agency.

But as with so many great European lives, the rise of Nazism forced a relocation. Setting up shop in Paris and assuming a new name in the hope it would make him sound more American and, therefore, more marketable, it was as Robert Capa that he took photographs of the exiled Leon Trotsky addressing an audience in Copenhagen – proof that his affinity for the left would flourish in western Europe as easily as it would have wilted in the east.

Capa’s other constant companion was controversy. From the authenticity of his celebrated Falling Man picture to claims that he might have been at fault over the loss of most of his D-day images, not only was Capa often in the critics’ crosshairs, sometimes he wasn’t even Robert Capa at all.

While working in tandem with his lover, the acclaimed German photographer Gerda Taro, he often used the Capa name to cover pictures taken by either photographer. As Capa explained: “I felt that, as I had Anglicised my name and as I had a growing reputation, it would benefit the both of us to share credit, especially since Gerda was German at a time when that was a considerable cross to bear.”

Whether there was more to this than credit sharing, it’s hard to deny the sincerity of Capa’s love for Taro. When she was crushed to death by a tank near Madrid in 1937, he threw himself at his work, hoping either it or his burgeoning alcoholism would heal the wound.

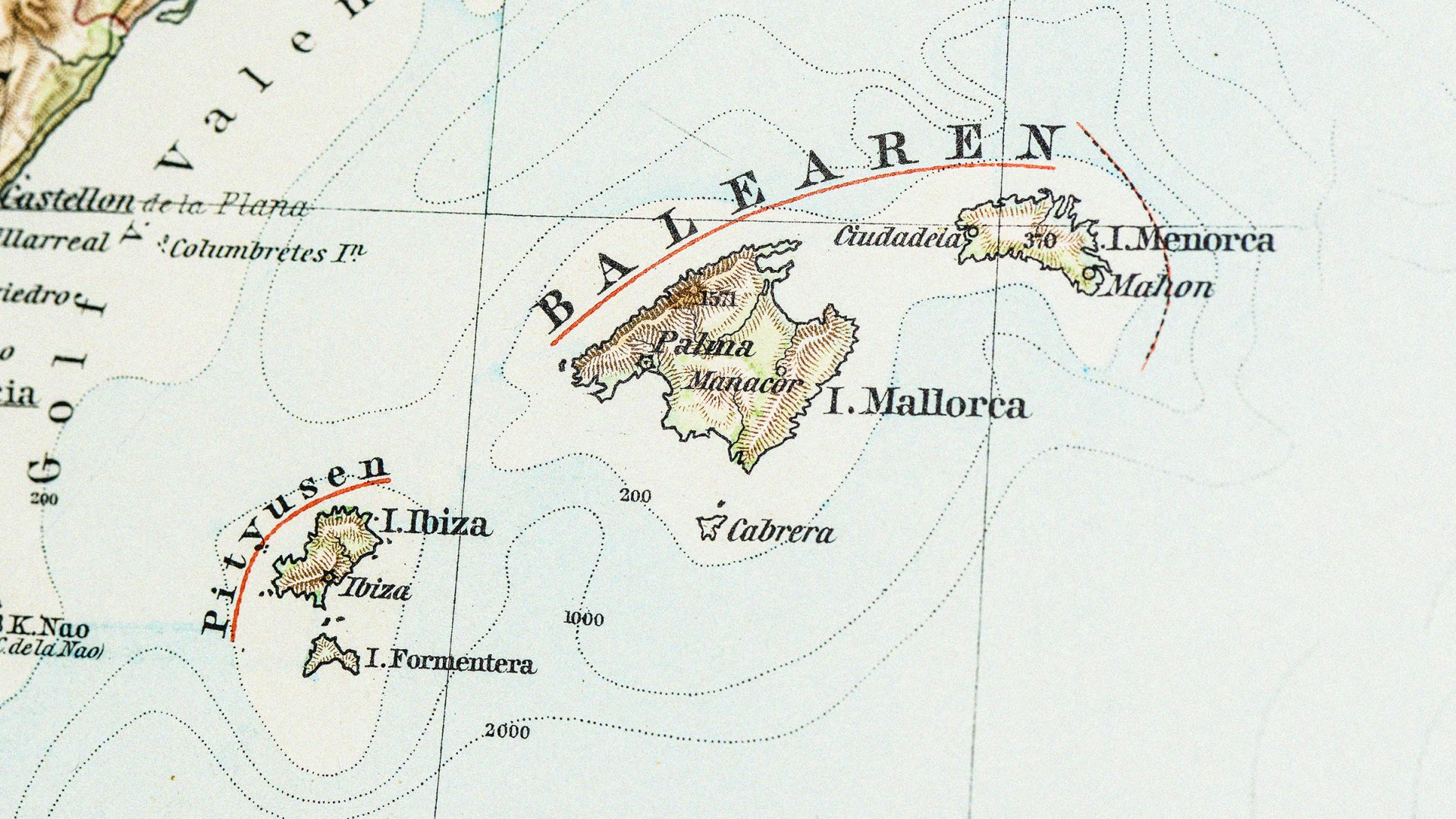

And so it was that Robert Capa leapt between armed conflicts with the speed of an ibex escaping a snow leopard. The Japanese invasion of China, the D-day landings, Stalin’s postwar Russia, the founding of Israel – no war was too small for Capa, no battlefield too bloody.

Sure, there was the odd glamorous assignment, such as serving as on the on-set photographer on John Huston’s Beat the Devil (1953). There was even an acting role in Irving Pichel’s Temptation (1946). Capa also had the romantic good sense to fall in love with Ingrid Bergman, a union that might have taken his life in a very different direction.

Capa, though, simply couldn’t resist the lure of the battlefield. In Japan to attend an exhibition in the early 1950s, he received a call from Life asking if he’d like to cover the first Indochina war. On May 22, 1954, he was rushing ahead to get a shot of French troops advancing when he stepped on a landmine. He was five months short of his 41st birthday.

Though he’s by no means the only war photographer to enjoy global acclaim, Robert Capa – together with Gerda Taro – was among the first to believe that a picture could change the public’s understanding of conflict. An egotistical belief perhaps and Capa certainly wasn’t slow in putting himself forward. But there was a self-deprecating sense of humour beneath the self-confidence.

Indeed, when he came to publish his memoirs, he used a common criticism of his D-day photograph of Hu Riley as the title – Slightly Out of Focus.